This article is part of the #GBVInMedia campaign for the 16 Days Of Activism global campaign to end gender-based violence. #GBVInMedia campaign analysis how different kind of mainstream media (mis)represents/reports gender-based violence and broadens the conversation from violence against women to violence against people from the queer community, caste-based violence and violence against people with disabilities. Join the campaign here.

Gender Based Violence (GBV) can be considered to be patriarchy’s tool to control women and other marginalized genders (or gender queer groups). It can often manifest in different ways; rape happens to one of them. Therefore, it becomes necessary to inspect how popular media portrayals of rape tackle the issue – is the narration subversive or does it end up solidifying misogynistic images in the society?

This particular article focuses on Hindi cinema in India. The Hindi film fraternity is huge in terms of the business it does, as well as the reach it has in the country.

Rape in itself is treated as a taboo subject in majority of these movies – something that is not to be touched upon at all. Even if it is discussed, we find such an awkwardness around the subject matter, that does not do enough justice to the topic. At the same time, it also completely fails to highlight the gender based violence aspect of the issue. Not just that, rape and sexual violence faced by members of the LGBTIQA+ community is completely ignored. (Which is why the examples I choose to highlight in this article would mostly be for sexual violence against women, unless specified otherwise)

The first and foremost inquiry should be about the nature of the issue – what is rape? Quite simply, it is an act that is committed with a blatant desire to punish, control women and their bodies/sexuality; in order to keep them ‘in line’. Sadly, the treatment of the subject in popular Hindi movies is cold at best, and sometimes bordering on the offensive. In the 70s and 80s, rape was used to add sexual content and to sensationalize the plot. We have numerous scenes featuring on screen villains like Ranjeet or Shakti Kapoor as sexual predators preying on women. Even movies like ‘Insaaf ka Tarazu’, which might have been made to depict a victim’s pain and her fight for justice, had a long drawn rape scene – which actually ends up objectifying the victim’s body.

Then came the 90s and the focus shifted on the social ostracization and stigmatization faced by the victim. More often than not, the victim would be rejected and scorned by her own family. Who can forget the scene from ‘Hamara Dil Aapke Pass Hai’, where the female lead who gets raped, is rejected and insulted by her father because she is no longer qualifies as a ‘chaste’ Hindu woman! And then, we have the 1993 film ‘Damini’, which has since then become a cult classic (and the film name has been appropriated as a pseudonym for the late Jyoti Singh Pandey). The movie shows a woman taking a stand against her brother in law who rapes a domestic help.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E2ujKwsmVFk

The issues I have with these movies is the fact that somewhere they subconsciously focus on respectability politics, which are class and caste based. Often times, the victim is a side character who belongs to the lower rung of society and thus, her body can be violated – Again, these movies have rape scenes which objectifies her body. The movie makers often justify these scenes as something necessary to highlight the victim’s plea. Even if the female lead is raped, we can easily notice how much stress is put on the fact that the woman is pure and virginal – how her inner goodness qualifies her as the heroine! This sort of puts the character on a pedestal and she has to prove her purity again and again. But herein comes the important question – what about women who dare to cross the line of respectability? So then, by this logic, can rape be excused if it is committed against women who are sex workers? This line of thinking is problematic since it ends up segregating women and tries to fit them into the Mother-Whore dichotomy. And also, it totally misses the basic point about how rape is not wrong because it upsets the patriarchal concept of ‘izzat’ or honour but because it violates a woman’s right to bodily integrity.

On the other hand, we have movies like ‘Raja Ki Aayegi Baraat’ where according to a court’s ruling, the right way to punish the rapist is to get him married to the victim! As if that wasn’t appalling enough, she even ‘fixes’ him by the end of the movie because of her dedication and loyalty as his wife – and lo and behold! He turns into a good guy! This whole idea of how women can fix their rapists is hugely problematic as it puts an unrealistic expectation and responsibility on the victim. However, before we all can laugh and dismiss these movies as merely bad cinema – and claim that they have no real effect on society, the media has reported some recent cases where real life seems to be imitating art! And that in itself is pretty disturbing.

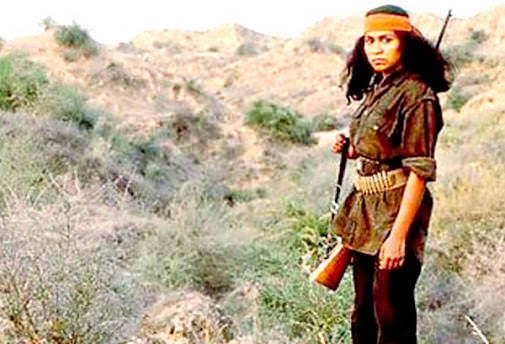

A lot of people say that commercial Hindi movies cater to a particular kind of audience and therefore it is a waste of time to look for content that is subversive in them. And ergo, one should instead turn to art house movies. However, sometimes even those movies can miss the intricacies of GBV. Let us take the example of ‘Bandit Queen’. A lot of feminist scholars have dismissed it as nothing more than a mere revenge rape movie. A very important point to be noted here is the fact that the director of the movie, Shekhar Kapur, did not even think it necessary to seek Phoolan Devi’s consent before making a movie based on her life. Arundhati Roy wrote a brilliant response to the film in her article ‘The Great Indian Rape Trick’ where she says

It didn’t matter to Shekhar Kapur who Phoolan Devi really was. What kind of person she was. She was a woman, wasn’t she? She was raped wasn’t she? So what did that make her? A Raped Woman! You’ve seen one, you’ve seen ’em all. He was in business. What the hell would he need to meet her for?

So in a way, the movie did not really capture the real voice of Phoolan Devi. Films that that do not take into account issues of ethics and consent – can’t do much except simply end up erotizing Gender Based Violence.

Therefore, it is clear that it’s not the commercial or art house status of the film that defines how rape as a subject will be treated by film makers. For a movie to qualify as truly revolutionary in terms of how it shows GBV, there are certain sensitive issues which need to be touched upon. The very basic question that haunts us all is -Where is the healing process? Why don’t these movies ever talk about the inner struggle of the woman, which by the way should move beyond societal ideas of respectability, honour, etc. Not just that, the journey of a rape survivor and her voice needs to come out well as opposed to a movie maker’s imagination. After all, if you are choosing a sensitive subject like rape and sexual assault, it would not do filmmakers much harm if they were to at least make sure that they produce content that does not objectify the woman. And most important of all, there should be enough clarity about how and why language matters – Whether a woman chooses to call herself a victim or a survivor should be up to her and her alone.

These are just some few points which can help make media representations of GBV more sensitive and feminist in nature.

Featured Image Credit: The Indian Express

About the author(s)

Writer. Gender activist. Sexuality educator. IT engineer. Loves Live.