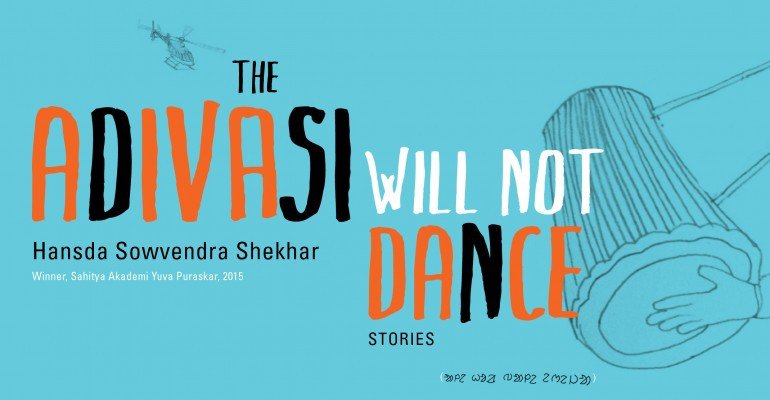

Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar’s collection of short stories, The Adivasi Will Not Dance, is a rarity in the English language Indian literary market. Shekhar is a Santhal – an Adivasi community belonging to Central and Eastern India – making him a unique voice in a field dominated by elite and upper caste writers.

Shekhar’s location as a medical officer in Pakur, Jharkhand is evident in the insightful particulars of his stories. They grant the reader an insider’s perspective into the life of Santhals and Jharkhand – a land that isn’t often fictionalised in mainstream Indian publications.

The book has a large variety of Santhal and non-Santhal characters spread across the socio-economic spectrum. They include – doctors and daily wage workers, homemakers and sex workers, government officials and goondas. Out of the ten stories in the book, more than half feature women protagonists or narrators. While a few of these characters are defiant and daring, most of the others are weighed down by the burdens of systemic injustice.

But it would be simplistic to describe them using a twofold lens of empowerment vs. disempowerment. As the book progresses, you get the feeling that Shekhar is telling it like it is. This was confirmed in a recent interview for the Telegraph, where he says, “Every story is scoured out of real life“.

the stories grant the reader an insider’s perspective into the life of Santhals and Jharkhand.

Three stories stand out in the collection. The first one called They Eat Meat! is about a Santhal family that moves to Vadodara, Gujarat in the early 2000’s. The undercurrent of communal violence lurks throughout the story as the Soren family is forced to quit eating meat so as to not upset the sentiments and caste purity of their neighbours.

This relinquishment is embellished by the protagonist, Panmuni-jhi’s ardent love for the food from her native land. The landlord also advises the Sorens to hide the fact that they are tribals from the rest of the neighbourhood.

When news of the Godhra riots hit, the Sorens lock themselves up at home like the rest of their neighbours. One night of the curfew, a mob of Hindu rioters enter their neighbourhood to attack the sole Muslim family that lives in the area.

In a heartwarming turn of events, the neighbourhood’s women come together to protect the women alone at home. They throw heavy steel utensils from rooftops at the mob to deter them. The same utensils that are used to cook ‘pure’ vegetarian food, thereby reinforcing a caste hierarchy, are now weaponised to protect the ‘outsiders’.

The interlinking of communal tension, caste and food practices in the story offers a telling commentary on how minority communities in the country have to toe the line to be accepted in different parts of the country. As Panmuni-jhi muses, “In Odisha, she could be a Santhal, an Odia, a Bengali. In Gujarat, she had to be only a Gujarati.”

Also Read: Cultural Appropriation Of The Dongria Kondh By Amoh By Jade

The last story of the collection is called The Adivasi Will Not Dance. It contains the lengthy musings of Mangal Murmu, a musical artist and troupe-master, on the wretched condition of his people after he is beaten up by the police for protesting the state-sponsored theft of Santhal land for a corporation.

His thoughts summarise the various ways in which Adivasis are used and exploited by land grabbers, merchants, missionaries, the media, corporations and the government. The story is inspired by actual incidents in 2013 when Adivasi farmers were arrested for protesting the building of the Jindal power plant in Godda, Jharkhand, as then-president Pranab Mukherjee laid the foundation stone.

In the rhetoric of development, land grabbing is often justified because it creates jobs for the ‘poor’. But the wealth generated by such development is seldom transferred to the hands of the people who owned this land. In return for its sale, the Adivasis receive toxic pollutants that infiltrate their water and the air they breathe.

As someone at the inaugural ceremony shouts “Bharat Mata ki Jai!”, Murmu deconstructs this deceptive take on patriotism. He ponders, “Which great nation displaces thousands of its people from their homes and livelihoods to produce electricity for cities and factories?…An Adivasi farmer’s job is to farm. Which other job should he be made to do? Become a servant in some billionaire’s factory built on land that used to belong to that very Adivasi just a week earlier?”

In the rhetoric of development, land grabbing is often justified because it creates jobs for the ‘poor’.

In August 2017, the book was banned by the Jharkhand government under accusations that its depiction of Santhal women was “denigrating and pornographic“. The key offending story was November is the Month of Migrations – about a young Santhal woman named Talamai who is exploited by a jawan from the Railway Protection Force.

In exchange for sex, he offers her Rs. 50 and two cold pakoras. Like the other stories in the book, the depiction of sex is crude and callous, clearly meant to make readers uncomfortable. But it is not offensive.

In fact, what SHOULD offend us in the book, is what should also offend us in real life. That is, the abuse, injustice and exploitation faced by the characters. As Hansda has said when asked to tone down his writing – “Why should the truth be whitewashed?”

Dealing with heavy themes such as sexual abuse, state-sponsored exploitation, cultural genocide and environmental degradation, this is not a book for the faint-hearted reader. Over the course of ten short stories, Shekhar weaves a rich tapestry, depicting a minority community living in the margins of India.

While Dalit literature in India has had a substantial presence in the limelight, Adivasi literature has largely been bound to regional languages. As an Adivasi and an avid reader myself, it has been uncommon for me to come across books written by Adivasi writers. This is why I am glad that voices like Shekhar’s are finally getting the attention they deserve.

Also Read: 5 Adivasi Women Activists We Should Know About

Featured Image Credit: Spectral Hues

About the author(s)

Nolina Minj is a freelance writer and researcher. She is a gender and decolonial studies enthusiast, book hoarder and Hispanophile.