Since, gender based violence has been on the rise, or has taken multiple forms in the contemporary neo-liberal world, the discourses around consent and its theoretical and practical meanings have begun to be rethought and reviewed. But what happens when certain human ‘abilities’ are taken for granted while constructing theories/rulebooks of interpreting and expressing consent in both legal and societal terms? Their neatly boxed categories get blurry, and a further reconsideration of these categorisations become necessary. Disability as an intersection is often considered as an “add on” category, where its role to mould and influence everyday life experiences often gets underplayed and fails to garner prominence as compared to other intersections of class, caste, gender, ethnicity, race or religion. There is an urgent need to recognise disability, both in its individual/isolated capacity as well as in its varied overlaps with other categories of identity that manifest itself into multiple forms of marginalisation in the contemporary society. Hence, the need of the hour is to explore the ways women with disabilities from South Asian countries (India, Nepal and Pakistan) negotiate or deal with the notion of consent, not simply with regards to sexual encounters but also in their everyday life experiences.

There is also a dire need to understand the aspect of consent through the lens of disability development justice in order to focus on the notions of intersectionality, inclusivity and affirmative actions by the state.

Consent: Interactions And Intersections

Consent as a concept might have been defined by various dictionaries in carefully arranged sentences, however, its real-life demonstrations have multiple meanings which are understood, interpreted and expressed by people in different manners. Even within the broader category of people with disabilities, consent and its meanings change across space and time, as well as with regard to other social locations within which they live. It also varies from one disability to another across the spectrums of mental and physical disabilities.

One of the most important aspects of consent is language and communication. Consent, in its most common and narrowed down expression is often verbal. The sentence, “No Means No” is expected of women to be spoken out loud for her perpetrator, in order for that person to acknowledge her right to consent.

Most people also assume that people with disabilities always need help or they need help in a certain way, without having the basic courtesy of offering help rather than directly helping. Especially for women with disabilities, as little as touch could be triggering, since women in general are made to feel uncomfortable by unsolicited touching.

Moreover, most people in the world have no knowledge of sign language, and honestly, if consent is not respected in spoken languages, the expectation to have conveyed consent in sign language seems far-fetched in this male-dominated, misogynistic world of patriarchy. Since, our non-disabled banalities of everyday reality excludes the experiences of people with motor disabilities, and that is where body as a language is acknowledged as an expression of consent.

Nidhi Goyal, a disability and gender rights activist and the founder and director of a Mumbai-based NGO Rising Flame asserts in a panel discussion on how consent is understood and represented in pop-culture industries in India. A visually impaired person herself, she thinks that consent is thrown out of the window even for non-disabled, heterosexual women, where stalking, relentlessly chasing, harassing, touching without consent and using sexist language is portrayed as romance and love.

She also believes that pop culture often tries to defend bad representations by using the most common excuse of “reflecting a certain kind of reality” to which she counters by saying that it simultaneously influences the society we live in. According to her, “Consent, particularly in romantic and intimate spaces gets confused because of popular culture.”

Nidhi, in her speech, also emphasizes the regular nature of expressing consent as a person who requires assistance by another person in many everyday circumstances. People navigate consent on a daily basis and for her, “Consent begins at the very simple question of, “What do you want to eat?” or “How do you need help?”.” Hence, consent and the discourse around it needs to be rethought beyond romance and intimate relationships. Most people also assume that people with disabilities always need help or they need help in a certain way, without having the basic courtesy of offering help rather than directly helping. Especially for women with disabilities, as little as touch could be triggering, since women in general are made to feel uncomfortable by unsolicited touching.

The other end of the spectrum is the generalised idea of being unable to perceive people with disabilities as sexual people. Hence, the discourse on consent is restrained then and there, where non-disabled people and their prejudiced minds cannot imagine PWDs having sex or sexual partners. Adding to that, is the double or triple burden that women with disabilities are confronted with, where they are often questioned about their “inability to “satisfy” their partners”, in heterosexual and normative marital relationships.

They are often encouraged to get married to other people with disabilities and, preferably to men with the same disability as theirs. They are also forcibly made to feel inferior and grateful to their male partners, who have ‘accepted’ them and their disability. Socialised into such patriarchal values, they often find it difficult to quit toxic relationships. It is also important to point out that there is a great emphasis on finding a partner for women with disabilities, since they are perceived as incapable of living on their own.

Disability As We Know It As Opposed To Disability As It Is

Talking about women with disabilities, the two main obvious points of intersection that are examined are gender and disability. However, our lives are not compiled in such fine lines of identities. They have to be understood in relation with the socio-political and economic contexts of the society.

Women with disabilities from developing countries have been systematically excluded from developmental agendas sponsored by the State. Be it in terms of architectural developments, employment opportunities, support groups, financial support or inclusive policies, women with disabilities either find themselves under the broader umbrella category of either women centric rights or disability rights.

Apart from lack of inclusion at the policy level, there is also an added burden of societal exclusion and stigma, where people with disabilities are viewed with pity along with an overprotective attitude or are simply looked down upon as incompetent. They are discouraged to travel, move to places to access education and employment, to participate and lead a ‘regular’ life, even if they wish to.

For women with disabilities, to live in a world which stigmatises disability and is essentially patriarchal, the “insecurities” around women’s safety gets amplified and hence, the curbing of violence against women with disabilities takes place at the cost of their freedom(s). Hence, not only consent with respect to sexual encounters, but also the consent to live, to move around and to choose in everyday life has a crucial part to play.

Abia Akram, a disability rights activist from Pakistan and a woman with physical disability herself, who has been working in the disability sector since 1997, narrated in a podcast hosted by APWLD (Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development) how her friend in school was given a prize because she had befriended Abia. These instances of micro politics where Temporarily Able Bodied People or TABs are applauded for doing the bare minimum tells us a lot about the failure of the state at macro levels to make disability-friendly spaces.

The language around consent too has to be reimagined with respect to women in general and women with disabilities in particular. Along with that, there is an urgent need to discuss, debate and add on to the existing discourse on consent and disability to identify the problems and try to mitigate them. Sensitisation on consent should happen at all levels, whereby even women with disabilities should be provided with information around consent, legal literacy and their rights and resources.

It is a double edged sword because, while at one hand, people with disabilities demand recognition and provisions from the society and the governments, on the other hand, they also wish that the society would normalise their existence and perceive them as people beyond their disabilities, rather than reducing them to their disabilities.

Also read: 10 Women With Disabilities Whose Achievements In 2018 We Should Be Celebrating

Then, How Do We Become More Inclusive In Our Activisms?

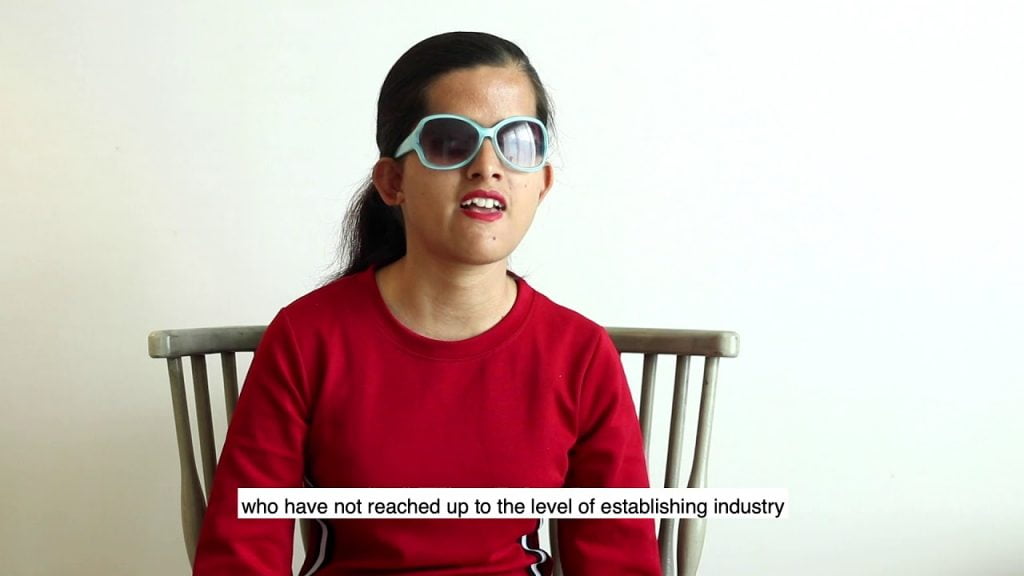

Laxmi, a disability rights activist and the general secretary of Blind Women Association, Nepal, an organisation that works for the rights, inclusion and empowerment of women with disabilities in general and visually impaired women in particular works for planning and implementing policies that take into consideration the various intersectionalities that women live with. One of her works deals with intersectionality effectively within her local contexts of Nepali ethnic communities.

For her, “Madhesi women with disabilities are marginalised with regards to their gender, ethnicity and disability”. She wants to look at such different points of intersections because, although Nepal does have reservations and provisions for women in general, but the state has not been able to look at the specific ways disabilities manifest itself into structural barriers that hinder equal participation of all women, and not just women with privilege.

A holistic and general approach to ensure inclusion could begin with community building, whereby people with disabilities are not isolated and have a space for interaction with other people with disabilities to discuss ways to fight the societal challenges that they are confronted with. However, this should not imply that once a community is built, the entire community is kept separate from the non-disabled, mainstream spaces. There is a constant need for dialogue and discussion in order to increase the representation in policy spheres. This will result into the redistribution of power, which is mostly held by non-disabled heteronormative men at every levels of governance.

The language around consent too has to be reimagined with respect to women in general and women with disabilities in particular. Along with that, there is an urgent need to discuss, debate and add on to the existing discourse on consent and disability to identify the problems and try to mitigate them. Sensitisation on consent should happen at all levels, whereby even women with disabilities should be provided with information around consent, legal literacy and their rights and resources. Further, NGOs, companies and stakeholders who are working with these women too need such sensitising programmes, so that they can devote their honest attention towards women with disabilities and their issues.

Developmental justice for people with disabilities are as complex as their realities, and there is a dire need to bridge the social, economic and political gaps, when formulating and implementing policies. One of the most obvious ways states across the world could do that is by increasing representation of people with disabilities in social and political sectors.

Also read: 6 Books By Indian Women With Disabilities On The Unequal Society

Women with disabilities should be facilitated with education, viable infrastructure, safety, financial security, access to land, equal wages and resources to encourage them into participating in the public spheres, not simply as representatives from the disability sectors but in “mainstream” political, educational and bureaucratic departments. Their voices should be recognised equally important for making general laws on citizenship, minority rights and other broader policies. This way, violence against women and gender inequalities can be alleviated.

This article was written with the help of recommendations from the Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development (APWLD) for the Beijing +25 Regional (Asia Pacific) CSO Forum.

About the author(s)

Pragya is a Master's Graduate in Sociology from Jawaharlal Nehru University. She works as the content editor at Feminism In India. She is also a ramen enthusiast, a hummus mother, a postcard hoarder and a wannabe cat lady. She still prefers writing on her notebooks, rather than on her laptop, but her job demands her to do just the opposite. Her favourite season is spring, and her alter ego is that of Mrs. Dalloway who said, "She would buy the flowers herself", in case no man ever buys her any!