Editor’s Note: This article is part of a campaign called #AdolescentSexuality, by Feminism in India and Partners For Law In Development, which focusses on the statutory criminalisation of underage sexuality and marriage by the State through laws like POCSO and PCMA, even when it is consensual in nature. To know more about the campaign, check out the hashtag #AdolescentSexuality on social media.

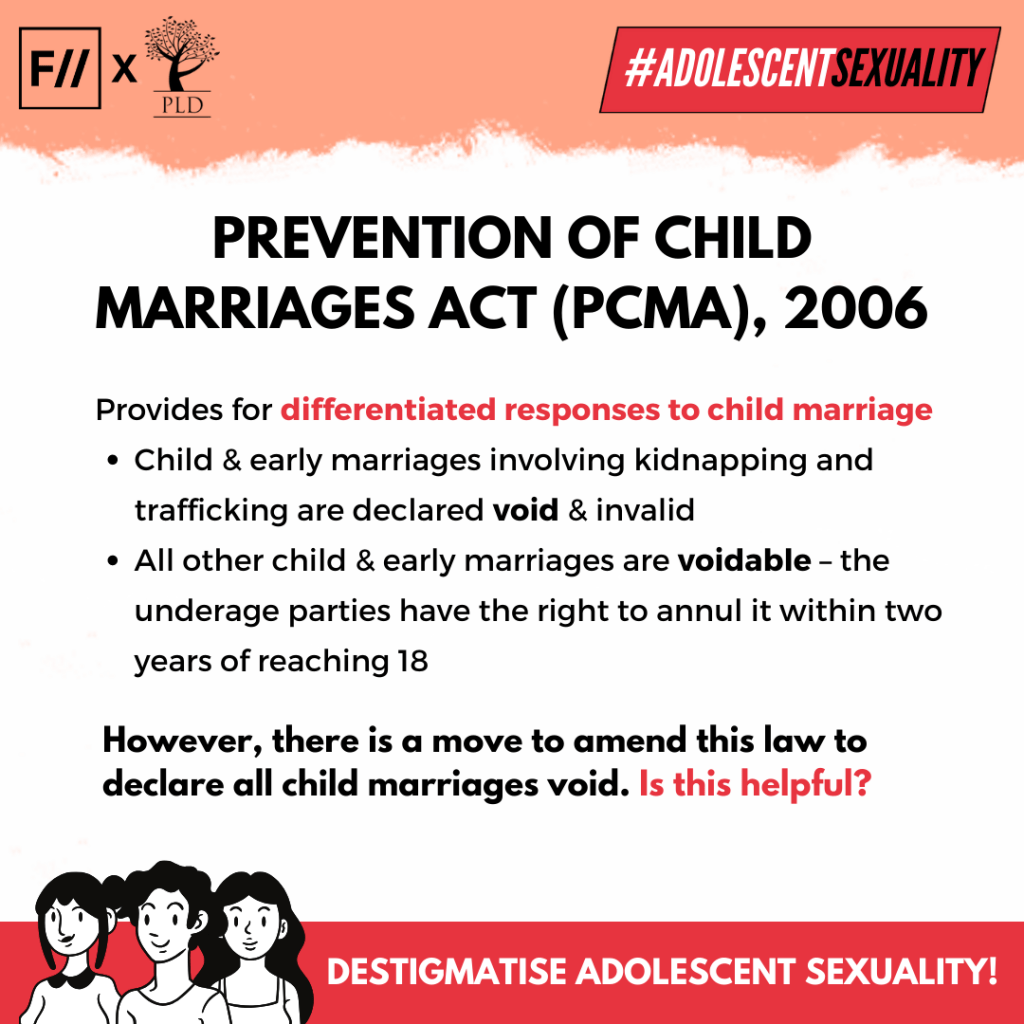

Child marriages. To the world at large, the words are meant to be understood as young girls being wed or sold to older men in pursuit of traditions. A social evil that must be eradicated to protect young girls from predation. Indeed, in the last few years, India has made its way into the global rush to meet the United Nation’s 5th Sustainable Development Goal to put an end to child marriages worldwide. The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006 (PCMA) was framed to replace the Child Marriage Restraint Act in order to forbid child or underage marriages, appoint Child Marriage Protection Officers to implement the law and penalise those that participate in the act including the adult party to such marriage.

Given the intention of the law, it would come as a surprise if stated that the PCMA in practice ends up causing unintended harm to a significant population of India; adolescents. Particularly, adolescents in self arranged marriages or elopements.

Adolescence is a distinctive phase arising out of childhood and blending into adulthood that is marked by psychological and biological development. Individuals within the age group begin forming their own agency as well as expressing and exploring their sexuality. Hence, adolescents exploring romantic experiences and sexuality irrespective of class or cultural background is of natural consequence. However, class and marginalisation become more evident as factors when such experiences culminate to elopements.

Given the intention of the law, it would come as a surprise if stated that the PCMA in practice ends up causing unintended harm to a significant population of India; adolescents.

A, then 16 years old, met her boyfriend, 18 year old P, at a family wedding with whom she kept in touch via telephone. Upon learning that she was being set up to marry a person her father chose, she admitted to being in a relationship with P. She asked her father to be married to P instead who instead. However, her father told her to break off with him and fixed her match elsewhere. A eloped with P within a month of which her father filed a missing person report. A agreed to return on condition that P be accepted into her family. However once she did, her father filed a case against P charging him with abduction and rape, prompting A to run away again. This time she approached the police refusing to go home and was shifted to a shelter where she learnt she was pregnant. Her family having cut all ties with her, A lived out the time until she was 18 at the shelter with her baby son to eventually join P, who being let out on bail, continued to fight the case against him.

Perceiving marriage as compulsion in India is a reality that transcends religions, ethnicities, caste, class and culture. Add to this lack of resources, dearth of opportunities and intergenerational marginalisation – and the obligatory nature of marriage becomes far more obvious where there is little availability of alternatives. Adolescents in such vulnerable conditions take up ‘grown up’ responsibilities of bread-winning and household chores far earlier. This often comes at the cost of forsaking education and similar avenues that could help them expand their life choices. The situation gets further complicated with the prevalence of traditional segregation of gender in social life. Such a dreary course of living combined with social disempowerment, sexual stigmatisation, domestic abuse and little by way to address such issues, makes the distraction and positive validation through romantic partnerships far more attractive. Such partnerships also provide some semblance of choice to adolescents who, have no other resources to surmount their difficult circumstances. In fact, in conflict against parental wishes, such assertions are often associated with stigma for ‘bringing shame onto the family’.

THE lack of resources, dearth of opportunities and intergenerational marginalisation – the obligatory nature of marriage becomes far more obvious where there is little availability of alternatives.

Partners for Law in Development (PLD) who published their report Why Girls Run Away to Marry in 2019 based on interviews with girls who have eloped in across three Indian cities, found that most elopements take place around the anticipation or eventuality of parents finding out about romantic partnerships. Lacking means to address fear of backlash and familial abuse, adolescents are driven to take shelter in the ‘safety’ of marriage. Elopements for adolescents, hence, become the only way to validate such partnerships and retain their limited agency.

Law and Elopements

In light of the above, it is easy to infer that self-arranged underage marriages arising out of romantic partnerships amongst adolescents require differential treatment by law. The law, however, not only fails in such context dependent response, a closer look unearths where and how it is used and by whom.

PLD’s ongoing study of over 80 cases where the PCMA was invoked reveal that in most cases it is being done by disapproving families of eloping girls in conjunction with the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 (POCSO) and the Indian Penal Code (IPC) to incarcerate the husband on grounds of sexual assault due to the age of consent being set at 18.

Aarambh India (Prerna) in Mumbai worked on 260 cases where they found that about 25% were actually involved in consensual sexual relationships of which a large number were persons between 16-18 years. Instead of benefitting adolescent girls whom it is meant to protect, the reality reveals mounting criminal charges on their romantic partners despite their consent. Besides bearing the anguish of potential imprisonment of their romantic partners and husbands, girls themselves wind up facing retribution in one way or the other even where they aim to reconcile with their families. This involves being left at shelter homes, relocation, restrainment of movement and restriction of access to resources and isolation from peers resulting in mental and physical health implications.

Instead of benefitting adolescent girls whom it is meant to protect, the reality reveals mounting criminal charges on their romantic partners despite their consent.

More often than not, it results in forced betrothals or marriages of girls anyway. However, even in that as PLD’s other study Grassroots Experiences of Using the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006 highlights, the gap between the law and its implementation is so large that girls trying to exit or prevent forced marriages and agencies aiding them, often lack resources to use the law at all. Even where the law is used to prevent or exit such marriages, the risk of violence and retaliation to social workers and additional prospect of living in dreary conditions of shelter homes for adolescent girls are major hurdles.

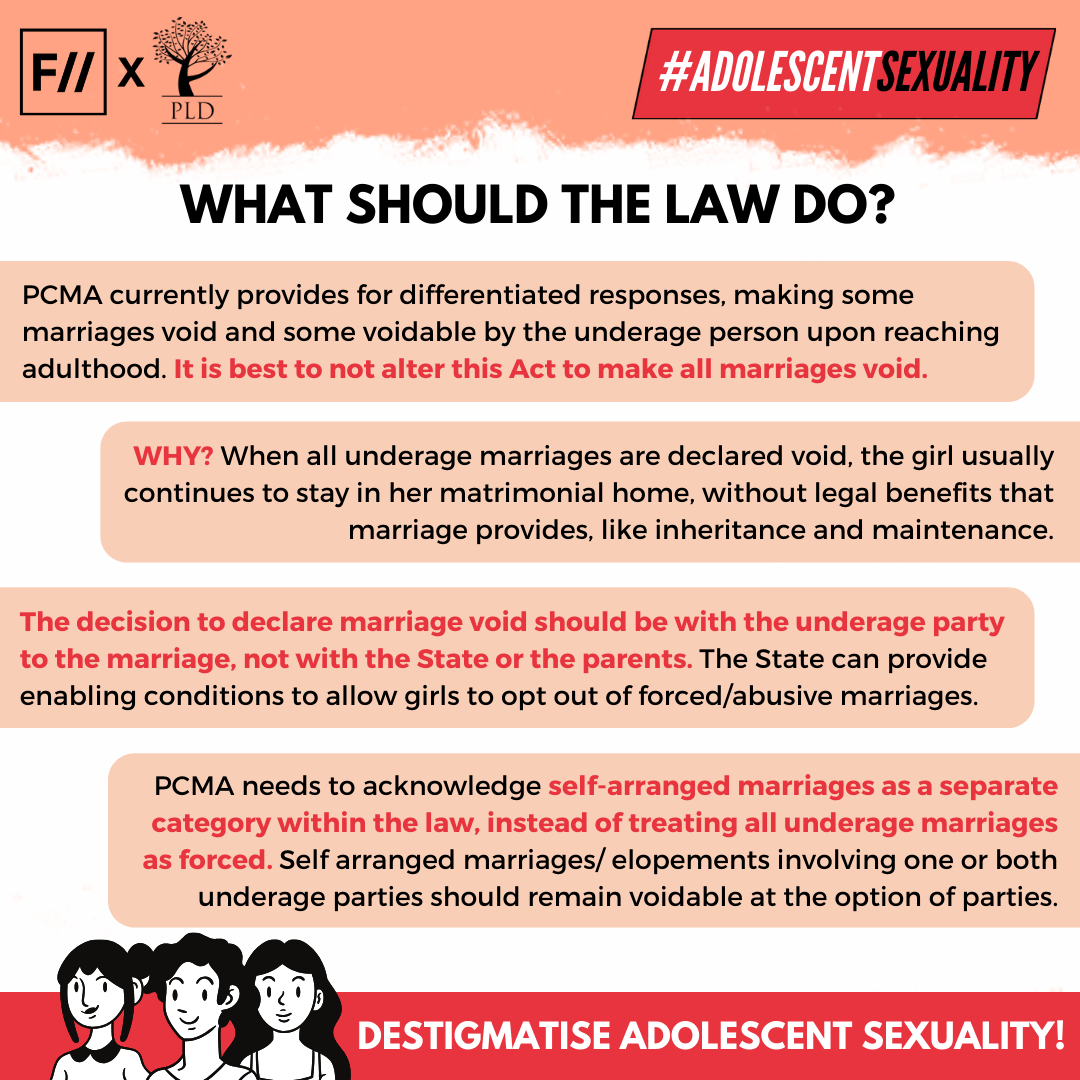

Recent reports also indicate pressure to further bolster the PCMA to nullify all underage marriages by making them void without exception. At present, in most of India underage marriages are voidable, meaning it is only void if the underage party so chooses. It allows for the underage party to opt out of marriage within two years of attaining majority if they should decide so. Upon opting out, the marriage is considered no longer valid in law without any retrospective effect on matrimonial rights of the underage party. Rendering every such marriage void and punishable does not only revoke agency, the harm of such turn of events extends beyond eloping adolescents. Lack of infrastructure and nuance in implementation of law does little to curb social perceptions of marriage where such events continue happening under the radar. In such a scenario, the underage wife is pushed to bear marital responsibilities without having access to the law. Bereft of matrimonial or maintenance rights and of secure social settings that she was previously guaranteed, she continues to live in her marital home, while her husband remains free to exit the marriage without any liabilities.

Things to consider

Therefore, the issue of underage marriages is a complex one when contextualised against individual agency and cultural expectations. While equipping adolescents with resources, tools and affirmative actions to make better informed choices exists an option, it is not an overnight process. In the meanwhile, what could be a more holistic way to analyse different trends within underage marriages and relationships?

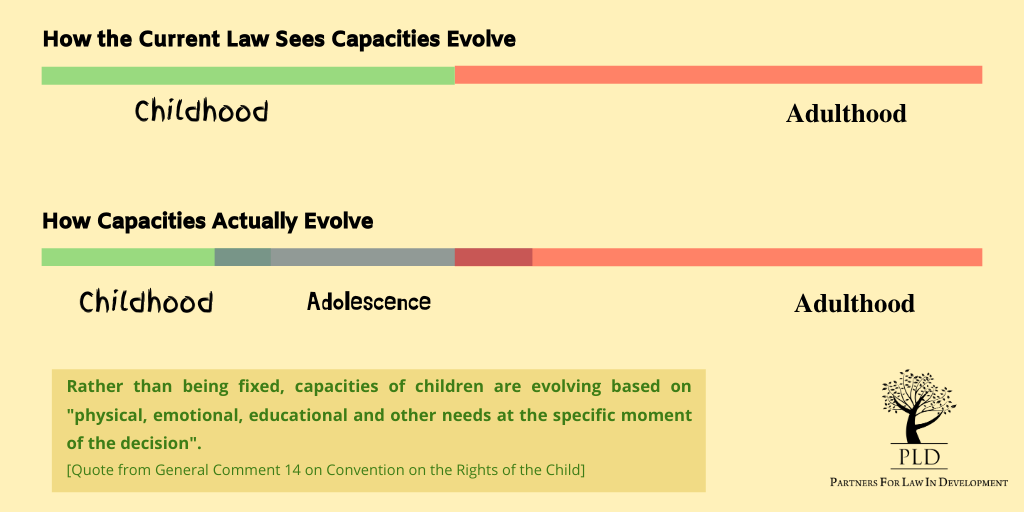

The current focus of law surrounding the debate on such marriages is increasingly funnelling singularly towards age where childhood and adulthood are considered binaries ignoring adolescence as a period of development and evolving capacity. It “infantalises all persons from 0-18 into compulsory abstinence, who suddenly assume maturity as they turn 18,” says Madhu Mehra, Executive Director of PLD. This is in contravention to recommendations of Article 5 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child which recognises evolving capacities and developing agency of children thereby attesting to the recognition of adolescence.

Marriage comes with its set of responsibilities and duties having different dimensions as against exploration of sexuality and romantic partnerships which are hallmarks of adolescence. We need to reconsider the benefit coverage of law where capacity to give sexual consent is considered the same as capacity to marry; where circumstances limit affirmation of sexuality to marriage; where the law is used as a measure to wield control over girls and criminalise young lives. As an alternative to ensure safer exploration of sexuality for adolescents, instead of pivoting on age, why not shift the focus to the gap in ages of parties to marriages? The National Commission of Protection for Child Rights recommends decriminalisation of consensual sexual relationships of children when engaged within individuals within a certain distance of age from them. Age of proximity based laws already exist in several other countries where adolescents are protected from predatory behaviour such as grooming by much older individuals while age of consent is kept at a reasonable bar.

The law as it stands at the moment provides adolescents the right to decide whether or not to nullify their marriage before or on attaining majority – and additionally, declares underage marriages involving coercion, trafficking and enticement from under lawful guardian’s keeping, as automatically void. On the other hand the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) 4 shows a steady decline of underage marriages, with 27% of girls in India being married under 18, while Census 2011 revealed that the mean age of marriage for girls increased to 19 years. What led to the decline in underage marriages and overall increase in the mean age of marriage for girls? Instead of calling for an outright ban of all underage marriages and expressions of sexuality, perhaps we need to ask, since the age of marriage is increasing still in the prevailing conditions, whether increasing the criminalisation of young lives is necessary to combat the issue?

Also read: Why Don’t We Talk About Adolescent Sexuality?

Udita is the Communications and Knowledge Officer at Partners For Law In Development (PLD India).

About the author(s)

A queer activist, feminist and former lawyer with an active interest in humanitarian causes. She loves photography, revising her Spanish lessons, studying cultures and history, and travelling (or reading about it when she can't).