This review contains spoilers.

Trigger warnings: Gun violence, graphic descriptions of violence, homophobia and corrective methods, rape.

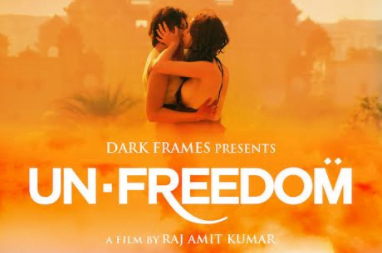

Unfreedom is a 2014 film written, produced and directed by Raj Amit Kumar following two narratives, one in New York about the kidnapping of an anti-extremist Islamic scholar and one in New Delhi, following a queer woman trying to break away from her homophobic family and a forced arranged marriage. The film touches upon various contemporary issues around religion, sexuality, gender, violence and family. One of the highlights of the film is its queer representation. Unfreedom was banned in 2015 by the Censor Board in India citing nudity and violence and was not released. The rights of the film were acquired by Netflix in 2018 and it has been available on the platform since.

The Plot

The story of Unfreedom follows Husain, a fundamentalist who is recruited to kidnap Fareed, a liberal scholar in New York who openly expresses his anti-extremist views. The voice of reason that resounds from time to time for Husain is of Najeeb, who tries to talk him out of his violent decisions. The story shifts to New Delhi where Leela is contemplating with a gun in her hand while preparations for her marriage are in full swing. She tells her father that she does not want to get married but since, it is of no avail, she contacts Chandra.

Leela’s relationship with Chandra is not clear but the latter helps her get to Sakhi, who is Leela’s supposed lover. Sakhi is an artist, and at her party where she is seen addressing the crowd about being comfortable and public about their queer identity. Leela walks in the party and despite Sakhi’s refusal, persistently asks her to get married. Lost and hopeless, she follows Sakhi and his partner and shoots him; she then takes both of them hostage. Sakhi escapes from the car and gets help for her partner who is now bleeding profusely.

Unfreedom is a 2014 film written, produced and directed by Raj Amit Kumar following two narratives, one in New York about the kidnapping of an anti-extremist Islamic scholar and one in New Delhi, following a queer woman trying to break away from her homophobic family and a forced arranged marriage. The film touches upon various contemporary issues around religion, sexuality, gender, violence and family. One of the highlights of the film is its queer representation. Unfreedom was banned in 2015 by the Censor Board in India citing nudity and violence and was not released.

However, she sends him off to the hospital with an auto driver and decides to go to an abandoned place with Leela. Back in New York, the police escort Fareed to his public address due to concerns regarding his safety. However, Husain kidnaps him under the pretense of getting his copy of the Quran signed. He takes Fareed to an abandoned warehouse where he tortures his assistance and moves to inflicting extreme violence on Fareed. All the while, there are flashbacks that Husain experiences but there isn’t full clarity as to what they pertain to. What follows is more violence inflicted on Fareed and his family, nothing short of something out of a horror movie and ample nudity when the focus shifts back to the queer couple, who also end up facing extreme graphic violence in terms of corrective methods.

Identity, Family and Violence

While there is no connection between the two narratives in Unfreedom, except for a few similarities, the main characters are primarily their identities with much less focus on their backstories. The film follows the violence that Fareed and Leela face due to their identities and the stands they take because of them. Family plays a big part in this violence. Fareed’s suffering is amplified by the violence that Husain inflicts on his wife and son, causing destruction to their home, tying them and using his gun and butcher knife with little hesitation. Husain then challenges Fareed to forfeit his beliefs at the expense of his own life. One can see points where Husain is torn between his violent flashbacks and part of him that wishes to stop but he ends up causing irreversible damage at the end.

In New Delhi, Leela leaves a heartfelt message for her father Devraj, asking for acceptance for her sexuality. Her father in reaction feels humiliated and starts what can be called a witch hunt for his daughter and the woman he repeatedly labels “whore”. Devraj has the full support of the police and is told by an inspector, “Meri beti hoti toh usse kaat deta”, (if she was my daughter I would’ve cut her) a line that he repeats to his daughter later as she is behind bars. Leela, who shows little respect for Sakhi’s decision and goes as far as to take her hostage is elated by the time she gets to spend with her. There is a montage of the two on a beach with an abundance of nudity and expression of sexuality until they are caught and put behind bars.

Devraj gives Leela the choice of picking her family over this “whore” and how he would forget everything that happened, expecting Leela’s gratitude that he allows her to live and not kill her in the name of the dishonour and shame she’s brought to the family. When Leela and Sakhi stand together against him, he signals the men at the police station to do something shocking, that is, inflict violence and rape. He watches his daughter and her lover being subjected to the corrective methods and takes Leela back home after.

The way that the characters face violence due to their identity and the involvement of the family is very different but shows the role that families play in identity and honour. Religion plays an important role for both Leela, who wishes to pray away her queerness and yet when she can’t, still continues to believe in God, and Fareed who considers his beliefs to be the real representation of Islamic beliefs and tries to guilt Husain for bringing a bad name to being a Muslim.

The way that the characters face violence due to their identity and the involvement of the family is very different but shows the role that families play in identity and honour. Religion plays an important role for both Leela, who wishes to pray away her queerness and yet when she can’t, still continues to believe in God, and Fareed who considers his beliefs to be the real representation of Islamic beliefs and tries to guilt Husain for bringing a bad name to being a Muslim. While Unfreedom was aimed at disturbing the viewers, the immense representation of violence borders it somewhere in shock value and some sort of sadistic voyeurism.

Also read: Film Review: Fire —On Queering Love And Beyond

Representation and the Male Gaze

Unfreedom is one of the films that a person would find under the tag of LGBTQ+ movies on Netflix, intriguing the viewer since that part of the movie is set in India. However, it is imperative to analyse and understand what the film presents when it deals with LGBTQ+ representation. The film seems to have shown the members of the community in a very hypersexualised light.

This is evident at the very start when Sakhi is shown painting nude figures without clothes, all her art which is only around nakedness as if to say being naked is always sexual or is the only way to represent sexuality. The party where Leela finds Sakhi is at the house of a gay man which again has explicit sexual symbols all around the house as decor. Everything about Sakhi and Leela’s interaction is laden with sexualisation, including just any expression of love between the two. There is no denying that nudity is empowering for some, but it seems so forced in the film as if the film would’ve seemed incomplete to the makers without it.

While Unfreedom centres around identity, for the queer characters it is their identities and bodies. The male gaze of the film transcends the storyline and caters to the audience abundantly. Womxn, trans folx and members of the LGBTQAI+ community face enough stigma in the society regarding the expression of the sexuality, sexualisation, objectification, fetishisation, often deemed subhuman and accorded a hypersexual nature, so much that this film proves distasteful in its representation. The male gaze of the viewer is satisfied with the forced nudity and the homophobia and misogyny are settled with the corrective methods of violence and rape, both on and off-screen. There is queer representation in Unfreedom, we need more representation, which is adequate and accurate.

The Relevance of the Film, Five Years Later

The film received harsh criticism both by critics and the audience. The expectations of the film increased for the viewer more since it was banned for reasons of violence and nudity, however, the forbidden nature of the viewership wears off soon and shock value that the film is so full of becomes starkly clear. However skewed film and its representation might be, it brings up the question of censorship and the state’s determination to forbid certain art which may make people question the status quo.

Also read: ‘Boy Erased’ And ‘The Miseducation Of Cameron Post’ Show The Horrors Of Gay Conversion Therapy

At the same, the violence and corrective methods that the movie throws light upon are not alien or false. There has been an influx of news in recent times exposing conversion therapy and corrective methods that lead to life long trauma and in some cases death of the LGBTQAI+ youth. These concerns still need immediate acknowledgement and addressing.

Featured Image Source: Sakal Times

About the author(s)

A spoken word poet, writer and a graphic design enthusiast, studying education. Passionate about a wide range of things, anywhere from political theory to queer representation to artificial intelligence.