Posted by Anurati Tandon, Vishal Kansal

Women’s empowerment is a critical driver for economic growth and social prosperity. Broadly, the term refers to an improvement in women’s political, social, educational, economic, and health status. Beyond individual women, it has far-reaching benefits for their families and communities as well. For instance, research indicates that women’s empowerment is positively associated with improved health, education outcomes for children, and increased competitiveness on human development indicators. By 2030, India has committed to making sure that women and girls contribute as equal partners to the growth and development of the country under Sustainable Development Goal (SDG)-5. However, according to the recently released Global Gender Gap Report 2020, India ranks 140 among 154 countries. In this context, how much progress have we really made towards achieving the goal of gender equality under the SDGs?

Findings from the first phase of the 5th National Family and Health Survey (NFHS) were released in December 2020. Our analysis of the data and trends captured by the NFHS-5 across 18 states and four union territories has helped us better understand where our performance should be celebrated, and where it is being held back.

Also read: Gasping For Breath: The Problems Of Private Healthcare In India

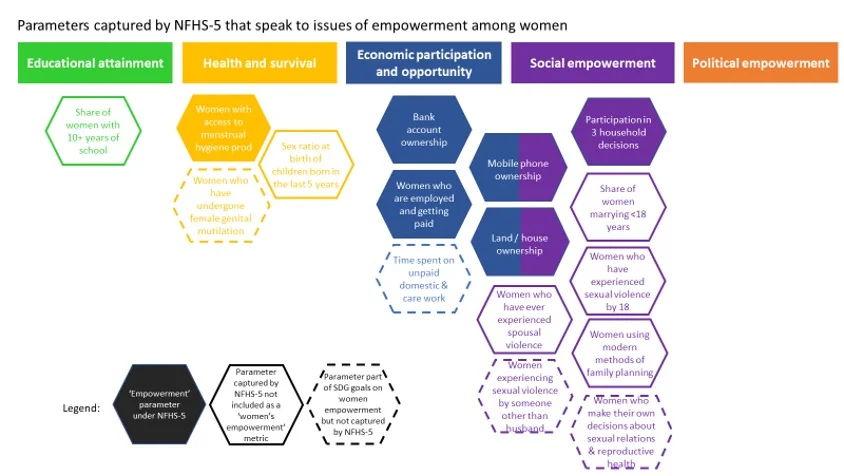

In India, the NFHS measures women’s empowerment, albeit in a narrow sense. It measures six factors—three related to ownership of physical assets (mobile phones, bank accounts, land, and housing), access to menstrual hygiene products, participation in three key household decisions (healthcare for herself, household purchases, and visits to family or relatives), and employment status over the last year.

Understanding women’s empowerment in the context of the NFHS

In India, the NFHS measures women’s empowerment, albeit in a narrow sense. It measures six factors—three related to ownership of physical assets (mobile phones, bank accounts, land, and housing), access to menstrual hygiene products, participation in three key household decisions (healthcare for herself, household purchases, and visits to family or relatives), and employment status over the last year.

Additionally, several other parameters captured by the survey also help measure empowerment. These include the incidence of gender violence, marriage under the age of 18, educational attainment of more than 10 years, and so on. However, these do not fall within the survey’s ‘women’s empowerment’ bucket.

It’s worthwhile to note that several important indicators which are a part of the SDGs are not yet captured by the NFHS. These include measurements around time spent on domestic or unpaid work, decisions on reproductive health, and the incidence of genital mutilation, among others. Indicators on aspects of political empowerment, such as the perception of women in their communities, are not tracked at all in the NFHS.

We have made some progress on metrics around education and health

According to our analysis of the NHFS-5 data, the share of women with more than 10 years of schooling has increased by 5.5 percentage points when compared to NFHS-4 data from 2015.

Educational attainment for girls has improved

According to our analysis of the NHFS-5 data, the share of women with more than 10 years of schooling has increased by 5.5 percentage points when compared to NFHS-4 data from 2015. The gender gap between the share of men with 10 plus years of schooling and the share of women with 10 plus years of schooling has decreased to eight percent (from 11.5 percent in 2015).

Improvement in two key healthcare indicators tracked by the NFHS

Menstrual hygiene and sex ratio at birth are two indicators that have improved over the past five years. The share of women using hygienic methods such as locally prepared napkins, sanitary napkins, tampons, and menstrual cups during menstruation has increased from 60 percent to 78 percent. The sex ratio at birth has also improved and now stands at 942 females for every 1,000 males. We are making slow progress towards our SDG goal of 954 females for every 1,000 males by 2030. However, urban areas with 928 female births for every 1000 male births continue to lag behind rural areas, where there are 947 females for every 1000 males. Better access to scans and sex determination tests in urban clusters likely to contribute to this.

Yet, on several social and economic parameters, our position is stagnating or worsening.

Also read: Maternity Benefits Must Be Extended To Tackle Child & Maternal Malnutrition

Input variables for economic empowerment are showing improvement, but key output variables are stagnating

Several input indicators that drive women’s economic participation, such as bank account ownership and mobile phone ownership, have jumped by 28 percentage points and 10 percentage points respectively since 2015. The government’s Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana scheme, increasing prevalence of the internet in day-to-day life, and the low costs of mobile phones and data are likely explanations for this increase. On the other hand, key output variables such as the share of married women employed and getting paid still stands at a mere 28 percent—an improvement of only two percent since 2015 and a decline of two percent as compared to 2005. This is driven by a significant reduction in women’s participation in the country’s labour force. (Given the absence of female labour force participation from NFHS-Phase 1 data, we have used Economic Survey data as a proxy.)

Factors that prevent women from entering the job market include increased rural mechanisation, an increase in education levels that may not be matched by equivalent job creation, and several other socio-cultural factors such as safety concerns associated with certain types of jobs, the burden of unpaid care, and so on.

Metrics relating to cultural attitudes are proving to be particularly troubling

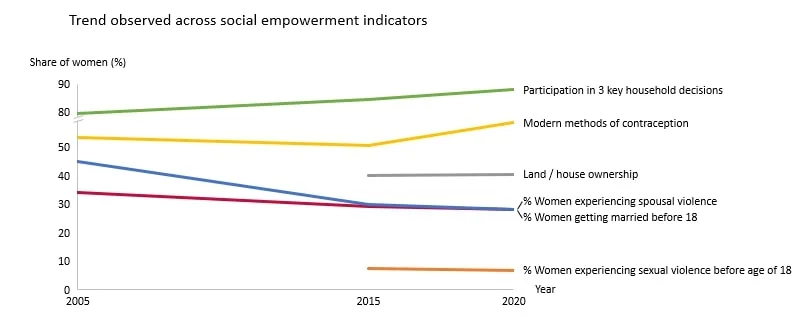

While participation in household decisions (already at around 85 percent in 2015) continues to rise, most other trends are stagnating or worsening:

- In 11 out of 22 states, land or homeownership among women has reduced.

- The share of women marrying below the age of 18 continues to be close to 30 percent—similar to 2015 levels.

- Trends around spousal violence are also stagnating, with almost one in three women having had experienced some sort of physical or sexual violence from their husbands. The survey was conducted before the lockdown, and the fact that domestic violence has surged during the pandemic—an approximately 60 percent increase between November 2019 and 2020—is likely to have worsened these trends.

- Despite an increase in modern family planning methods, the burden of family planning continues to fall largely on women, with female sterilisation accounting for more than 60 percent of total contraception usage.

Worsening trends can be attributed to a complex interplay of socio-cultural, policy, and political factors

It’s worth noting at this point that the share of the Union Budget spent on women-related schemes has been stagnant at approximately 5.5 percent since 2009 and less than 30 percent of which is being spent on 100 percent women-focussed schemes. A closer look at the Ministry of Women and Children’s budget on women empowerment shows that spending on schemes declined from INR 640 crores in FY 18-19 to INR 310 crores in FY 19-20. In FY 18-19, only 55 percent of the allotted budget of INR 1,200 crores was spent. On the face of it, the government has advocated for many progressive schemes such as ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao’. But in reality, nearly 65 percent of scheme spending has been on advertising, with very little focus on grassroots engagement. This is, in many ways, the root of the problem—changing gender norms takes patience and meaningful investment in on-the-ground work alongside national dissemination campaigns.

Stagnation in the share of women getting married before 18

Despite an increase in education levels of girls in India, the share of women getting married before 18 has not seen a marked improvement in the last five years. Sector experts suggest that economic stagnation among low-income families and higher dowry demands for older women are some of the reasons behind why families might prefer marrying off women early. The recent move towards increasing the minimum marriageable age for women to 21, without addressing underlying gender norms may actually worsen the condition of several women. One reason for this is the low conviction rate for early marriage cases in India, which was 23.8 percent for cases reported in 2018, with 84 percent cases still awaiting a judicial decision.

Increase in spousal and sexual violence towards women

Domestic violence is a global epidemic, with one in three women experiencing physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner. The increase in violence towards women, even before the lockdown, could potentially be related to an increase in economic responsibility on men due to economic stagnation and the availability of fewer jobs.

What next?

We need an exhaustive measurement of empowerment metrics

To get a more adequate assessment of the trends around empowerment, we must expand the basket of indicators and assess how they move holistically, rather than just focusing on the six that lie within the ‘women’s empowerment’ bucket of the NFHS. In order to track our movement on SDG indicators, we must ensure that bottom-up surveys like the NFHS are measuring what is critical, and not just what ties in easily with schemes.

Government can move away from a focus on an input-driven welfare model

Improvements in physical conditions are only one part of the empowerment equation. There is room for government schemes to be more intentional about shifting gender norms to create empowerment and potentially move towards an information, education, and communication framework. This has the potential to empower people to make decisions and change attitudes—the need of the hour.

Philanthropy can play a bigger role in tackling these tricky challenges

A global survey of 26 of the largest foundations found that six percent of their philanthropic funding identified gender equality as a primary target (and nine percent went to gender as a secondary target). However, in India in 2019, only approximately 1 percent of total domestic philanthropy and CSR spending (approximately USD 22 million) is spent directly on schemes or programmes that aim to reduce gender inequality. Additionally, there is a need to test and explore interventions around cultural factors that can drive long-term attitudinal shifts. This can be a role for philanthropy given its ability to make long-term bets. These investments will then have a natural ripple effect on the work of nonprofits and civil society.

This piece was previously published on India Development Review and has been re-published here with consent.

Featured image source: The Economist

About the author(s)

India Development Review (IDR) is India's first independent online media and knowledge platform for the development community.