Capital accumulation and knowledge monopoly by upper castes has created the distinction of the few powerful who hire and the subservient who labour, creating a hierarchy favourable to capitalism.

The caste-based stratification of the Indian society continues to exist in highly tangible proportions as a result of endogamy, hereditary perpetuation of occupational rigidities, ritual superiority and the ideological principle of pollution and purity. Legal and economic transformations over the years appear to have improved the narrative of chronic discrimination, especially with the onset of privatisation and a tilt towards a capitalist regime.

Many believe that capitalism enabled Dalits to shake the manacles of traditional occupations and the dominance of rural-land-owning classes by creating jobs in private companies which pay them well, and allow for blurring of caste identities. Milind Kamble, the founder of Dalit Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DICCI), and its mentor Chandra Bhan Prasad told the Indian Express in 2013 that they saw capitalism as a better social equaliser than any reforms or individual efforts against caste.

Capitalism, they believed, had allowed Dalits to enter the markets which they were conventionally barred from. The way capitalism functions today, raises several doubts about these claims holding true anymore.

A capitalist economy centralises private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. It idealises a free market, with minimal government presence, so that fair competition and market-determined prices dictate who earns how much. Capital accumulation thus becomes an accepted outcome of such an economic organisation.

As an extension, a capitalist society embeds class-based divisions borne out of property ownership and wage labour, where social capital hasn’t been conceptualised yet.

In India, caste structures define social inequality, in which systemic accumulation of socio-economic capital and monopoly over knowledge have perpetuated the hierarchy, such that difficulty of upward mobility for labourers blunts the resource access even in the very long run

Colonial India has traces of capitalism taking roots in the Indian subcontinent. As merchant-control went beyond simple commodity trade to establishment of manufacturing units, raw materials, labour, and markets were potentially exploited. When political power gravitated from the monarchs to the British, they sought to govern social relations for trade’s benefit.

The stark cultural difference and diversity meant that challenging or redefining the social hierarchy would be difficult – so hierarchies altered only to keep production smooth and Brahmin authority intact. Even under British authority, the existing power dynamics of caste were reproduced – the Crown’s production and taxation systems subsisted on class-based hierarchy where the traditionally higher rungs provided administrative manpower and exerted control over the labouring class.

This ensured that colonial capitalism re-entrenched historic inequalities, and upheld the traditional ‘social order’ by the means of caste-based census, settling legal disputes according to caste superiority, and the likes.

It is this perpetual, unequal access to economic and intellectual resources – knowledge, capital, and markets – that marks the contestation to the ‘free markets as equaliser’ concept. It deepens the educational and social status divide, creating structural barriers for ‘lower’ caste workers to acquire well-paid jobs and/or reach top-notch positions

Capitalism works in an ecosystem of class-based hierarchy, where few hire and many labour. This ecosystem becomes oppressive when the division is derived from social inequality. In India, caste structures define social inequality, in which systemic accumulation of socio-economic capital and monopoly over knowledge have perpetuated the hierarchy, such that difficulty of upward mobility for labourers blunts the resource access even in the very long run.

Also read: The Argument Of Meritocracy Is Inherently Flawed. It Is Time We Put It To Rest.

Due to the occupational hierarchisation of caste, certain occupations merit less/no dignity and economic value. Hence, while capitalism might have initially broken occupational rigidities, it gradually reproduced the casteist organisation of labour and production, and Rakesh Tiwary’s observations on inequality explain the reason – Inequality diminishes the scope of overall growth and use of full potential, it replicates itself in every system due to resource differences, and it doesn’t correct itself in the long run. And hence, it perpetuates.

It is this perpetual, unequal access to economic and intellectual resources – knowledge, capital, and markets – that marks the contestation to the ‘free markets as equaliser’ concept. It deepens the educational and social status divide, creating structural barriers for ‘lower’ caste workers to acquire well-paid jobs and/or reach top-notch positions.

Under capitalism, their jobs are new, but the dignity and economic value offered to these jobs still fall in lowest rungs of the urban spectrum, and entering markets itself remains a challenge – this is how capitalism reproduces ‘upper’ caste hegemony in the corporate domain.

capitalism, with its infamous history of never attempting a challenge to social inequality, cannot be left unregulated. It is not a corrective tool – it never tried to erase the race-driven economic inequality in the West. It doesn’t reward merit as much as it rewards privilege

Thorat and Attewell (2007) articulated this in an experiment, whose results outline the private corporate entities’ preference of ‘upper’ caste Hindus over Dalits (and Muslims) with equivalent merit. This bias is often an outcome of many Dalits’ mediocre primary education (ill-afforded due to low incomes) and lack of social capital – scarce referrals and networks which still influence employment decisions everywhere.

Thus, ‘upper’ castes can access high-paying jobs with relative ease. Data on training/scholarships provided to Dalits by ASSOCHAM/FICCI/CII and their invariably low numbers of Dalit employees reflect the reluctance of the private sector to employ SCs/STs even as it is willing to pay for their education.

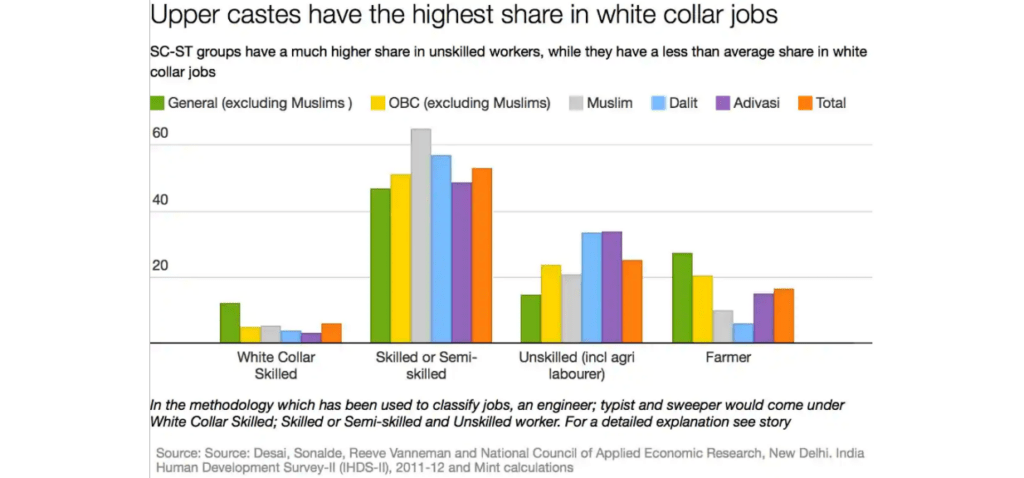

State of Working India 2018 report at CSE claimed the “over-representation” of SCs/STs in low-paid jobs, and that of ‘upper’ castes in well-paid ones. It also notes that the segregation observed in various industries typically follows caste dictations.

Suraj Yengde notes the disparate economic gains across social groups in ‘Caste Matters’ (2019) that, “The rich Dalits’ median income would come out to less than the median income of the non-Dalit middle class in total. So, a rich Dalit is still poor and wretched in the grand scheme of the caste–capital programme.”

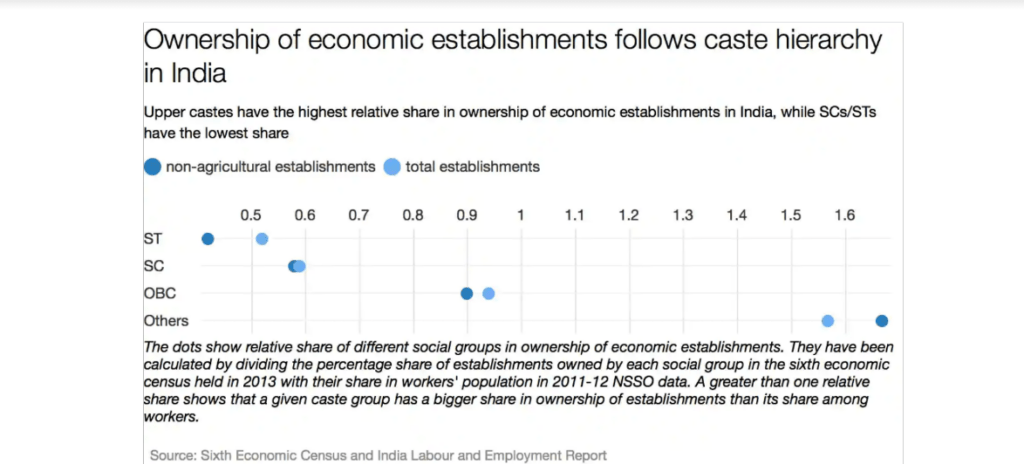

These charts reassert the over-representation of ‘upper’ castes in ‘white-collar’ jobs and enterprises. Caste-based divisions and employers’ caste bias are absorbed in the capitalist machinery and obscured under competition.

Ashwini Deshpande and Smriti Sharma (2013) had shown that the share of SC-owned firms in certain industries was far below the national average and the average of other social groups. It also highlighted the higher extent of segregation in urban areas. The difference of SC/ST presence in self-employed and casual-labour categories brings alive the disparities between who hires and who labours.

Earnest efforts beyond reservations are required in the private sector, which grasp the market’s tendency to make profits in the presence of inequalities. Social upliftment needs to be pursued with more vigour than ever if market is to become the decision-maker

As Geoffrey Hodgson writes, it is “inequality of inheritance” that creates inequality of wealth and cumulates into differences of education, economic power, and income. It is the differential of access to wealth in the scheme of inheritance, where land-owning ‘upper’ castes were traditionally able to transfer wealth and well-being to their descendants.

Against this backdrop, capitalism, with its infamous history of never attempting a challenge to social inequality, cannot be left unregulated. It is not a corrective tool – it never tried to erase the race-driven economic inequality in the West. It doesn’t reward merit as much as it rewards privilege.

Also read: Feminism And Capitalism: The Ideological Dilemma Of Coexistence

Earnest efforts beyond reservations are required in the private sector, which grasp the market’s tendency to make profits in the presence of inequalities. Social upliftment needs to be pursued with more vigour than ever if market is to become the decision-maker.

References:

Chakravarti, U. (2018). Gendering caste through a feminist lens. New Delhi: India.

Tiwary, R. (2006). Explanations in resource inequality: Exploring scheduled caste position in water access structure. International Journal of Rural Management, 2(1), 85-106.

Thorat, S., & Attewell, P. (2007). The Legacy of Social Exclusion: A Correspondence Study of Job Discrimination in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 42(41), 4141-4145

Featured Image Source: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism In India

About the author(s)

Riya Gangwal, an Economics student at Delhi University, is a fanatical reader, and a passionate poet and debater. She loves to research about policies for social change and economic development. When she is not philosophising failure, she is daydreaming of causing revolutions in her lifetime. She can be found on LinkedIn.