When I look back at my primary school years, I recall sunny afternoons scuffling with numbers in Maths till recess came to my rescue. The 30-minute break was simply not enough to neutralise the struggles of caustic long-form division. What all was a child to do in this? Eat tiffin (or exchange it with a friend), go to the toilet, play – before that it was also important to decide what game to indulge in. Then run back from the ground to class before the teacher made it there. It was not an easy world for a student, I must say. The next four periods after recess were agonising till the school day ended. Books and compass box packed in minutes before the bell – no time to spare!

For several years of my primary education, I was driven to school in Khanna uncle’s van service. During the early 2000s, private vans were commonplace, even more so than the school’s own bus service – the latter, after all, demanded twice the fees. Plus there was also the matter of trust. I remember being Khanna uncle’s favourite of our batch. The retired old man who himself was driven around in a wheelchair sat shotgun for every ride to and fro school. I spent many evenings perched on his lap, regaling him in my childish fables. On the days when the weight of the world lay heavy on my shoulders, he smuggled some sweets to lighten me up. My poison was Cadbury’s Five Star with its chocolate and gooey caramel goodness.

My school ended by 6.30 pm and by 7 pm I was dropped off outside the building gate. On most days, my mother was there to pick me up after her day’s work. At the time, she was employed by the LIC as an agent. She travelled around Mumbai’s suburbs meeting clients and selling policies. On most days, she stuck to her timetable and stood waiting at the gates of our society for my arrival. But Mumbai’s local trains – the lifeline of the city – are notorious for getting lost in time. They stand statued on the railway tracks (for a long list of reasons from accidents to signals to changing lanes) causing delays to the thousands of passengers it carried.

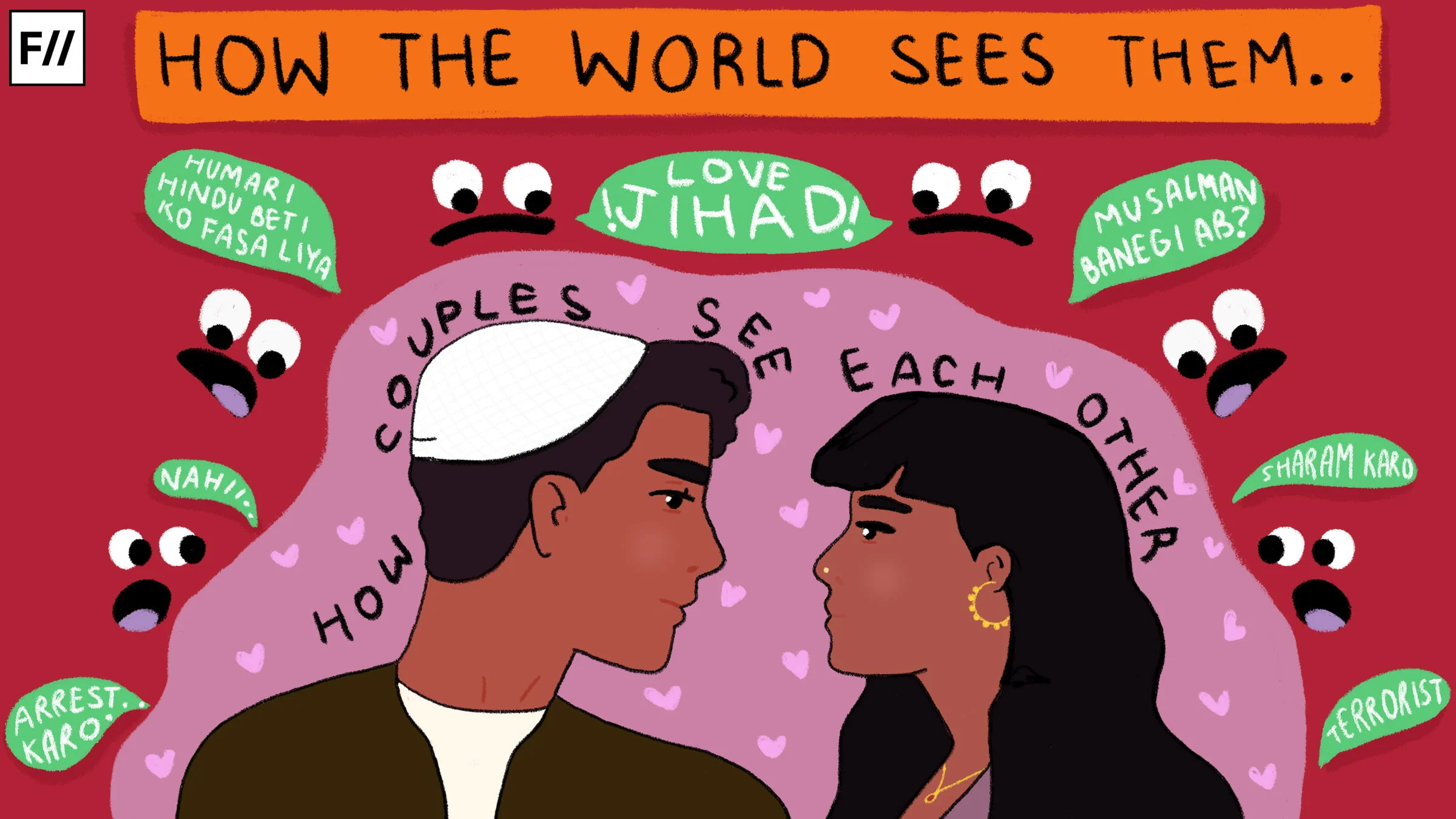

Also read: Communal Narratives & Fake News: Addressing Our Islamophobia

On the days that she ran late, I made my way to our neighbours’ flat, the Chauhans. By now, the sun had set behind the weary Mumbai skies, painting the inside of the buildings violet. The lights had still not been turned on but the entire corridor was filled with the smells of evening snacks – or at least that was my olfactory focus. These helped me guide my steps till I reached the third floor and in front of the Chauhans’ door. The Muslim family of seven welcomed me in high spirits every evening. Their house smelled of a khao gully with the kitchen loud and busy with dinner time preparations. In between her preparations, putting the cooker full of rice on the stove, Nargis aunty joined me with her cup of chai. She brought along a plate of my favourite snacks – chivda, bhakarwadi, cutlets, samosas, kebabs, you name it. It was meals like this that had me eagerly waiting for the month of Ramzan. My 8-year-old self knew that the month was considered all things important and holy but what mattered to me the most was the big spread of eatables. At the Chauhans’, Iftaaris were a grand culinary adventure.

The Muslim family of seven welcomed me in high spirits every evening. Their house smelled of a khao gully with the kitchen loud and busy with dinner time preparations. In between her preparations, putting the cooker full of rice on the stove, Nargis aunty joined me with her cup of chai. She brought along a plate of my favourite snacks – chivda, bhakarwadi, cutlets, samosas, kebabs, you name it. It was meals like this that had me eagerly waiting for the month of Ramzan. My 8-year-old self knew that the month was considered all things important and holy but what mattered to me the most was the big spread of eatables. At the Chauhans’, Iftaaris were a grand culinary adventure.

I often found myself asking for a sip or two of chai from Nargis aunty, resorting to making these requests in my sweetest voice. I was forbidden from drinking it in my house even though all the adults seem to enjoy it thoroughly – sipping from the saucer, dipping a khari or biscuit and biting it off before it sank to the bottom. It seemed rude to not share it with me. She sternly but politely declined and went on to produce a small box of Frooti instead. What more does a child need after toiling their day in school.

I also have a vague memory of spending the night before my first ever day at school at the Chauhans’. So thrilled was I to go to school that I wore my pinafore and spent the entire evening playing with their children. The family made several attempts at persuading me to keep the uniform away and ready for the next day but I wouldn’t budge. I ended up sleeping in it. My stubbornness saw me wearing the same stale outfit on my first day as a student.

The Chauhans’ two youngest kids were decades older than me but spent their evenings engrossed in my day’s saga, so much so that they forgot all about their grown-up homework. Kausar, their third daughter, almost always had her nose buried behind a sketchbook conjuring new designs for her henna class. During summer vacations, I offered her my palms, arms, feet and whatnot to practice her art. We spent hours chatting with long periods of silence, her focusing on being precise and me reading comics from a Tinkle. My mother didn’t care much for the temporary art on me then as long as I was somehow occupied. It must have come to bite her several years later when I got my arms inked, not once but a good many number of times.

There was something even I was to discover much later – years after we had moved away from the Chauhans, deeper into Mumbai’s suburbs up north. Kausar was confined to the bed and the sofa because of missed polio vaccinations – a grave misjudgment that Nargis aunty would regret for years to come, blaming it on lack of education and awareness. But it was a lesson learnt by the entire society that dared not to skip any polio doses thereafter. This was way before Amitabh Bachchan’s ‘Do Boond Zindagi Ke’ took over airtime and issued grave yet earnest warnings.

It was an unwritten rule – my mother would not eat or drink in their house, not even water. This was a rather unfortunate byproduct of her strict upbringing and decrees issued by her mother, my grandmother. She was allowed to be cordial, gossip, discuss politics and everyday chaos, but her mingling could only go so far.

Finally, when my mother returned from work to pick me up, she was offered only thanda. It was an unwritten rule – my mother would not eat or drink in their house, not even water. This was a rather unfortunate byproduct of her strict upbringing and decrees issued by her mother, my grandmother. She was allowed to be cordial, gossip, discuss politics and everyday chaos, but her mingling could only go so far. My grandmother, whom I remember fondly from long summer vacations and as my saviour from my mother’s mathematics-related wrath, was a nice, strong-headed woman. As loving as she was as my nani (maternal grandmother), she terrified my mother. Once my mother, back when she was known only by her maiden name, was invited to a Catholic wedding of a colleague. After an evening of merrymaking, when she returned home, my grandmother traced the smell of wine on her and beat my mother with a belt. It was only when my mother’s younger brother cut in that it all stopped. As young girls, this tale of terror was told to us warnings – ‘remember, you don’t have it as bad as us’.

For my mother, the ingrained othering of the kind people who looked after her very young daughter, fed her and kept her safe, felt wrong, but she couldn’t break out of the shackles even if she wanted to. For me to inquire where these teachings got root is not possible now – the deaths of both my grandmother and mother has now rendered the excavation impossible.

But what I know is that these commandments weren’t passed on by my mother to me and my younger sister – we were free from these divisive impositions that were supposed to separate our two communities. We were free to quench our thirsts in their homes, share our dabbas with them, lend and borrow stationeries during lectures, build friendships and relationships with the ‘others’. On those evenings, we sat together munching and chatting, filling the corridors of the middle-class housing society with laughter, glee and everything in between. Sharing the days’ woes and complaining that the government doesn’t seem to be working for the middle, working-class but only for the rich.

Also read: Sooryavanshi & The Glorification Of ‘Hindustan Ke Mussalmaan’

It is a strange feeling to recall those days today as an adult. My childhood seems simple and easy, aloof from the deadly chaos of the Mumbai riots that took place less than 2 years before my birth. That time seems tender and protected around the kind neighbours who allowed a small, chatty Hindu girl into their house to keep her safe from the outside world. I have vivid memories of the past but a strong sense of belonging too. My mother, who did not allow the othering to encroach on our upbringing, is a reflection of the many battles one fights with their conscience – of hereditary differences and nurtured love. Many evenings of my early school years were happily spent in that modest 1 BHK around a family that was happy to adopt me temporarily, feeding me all their specials and nurturing my future.

Pooja Salvi is a writer and a journalist who has, over the course of her writing career of more than six and a half years, worked with several English language dailies. From the Mumbai-based Afternoon Despatch and Courier to national dailies like Asian Age and Deccan Chronicle, and DNA, she has written over a range of topics – current affairs and women’s issues, feminism, sexuality, art, culture, city life, entertainment, music and books. She has a keen interest in literature and loves talking to authors about their books and dream projects. When not writing or buried in a murder mystery, you can find her napping with her cats. You can find her on Twitter and Instagram.

Featured image source: TheWire

About the author(s)

Pooja Salvi is a features writer exploring culture, people, and the nuances of urban life while shuttling between Bengaluru and Mumbai. She also publishes a newsletter on love, loss and grief.

You can follow her on Instagram at @sire_writeous.