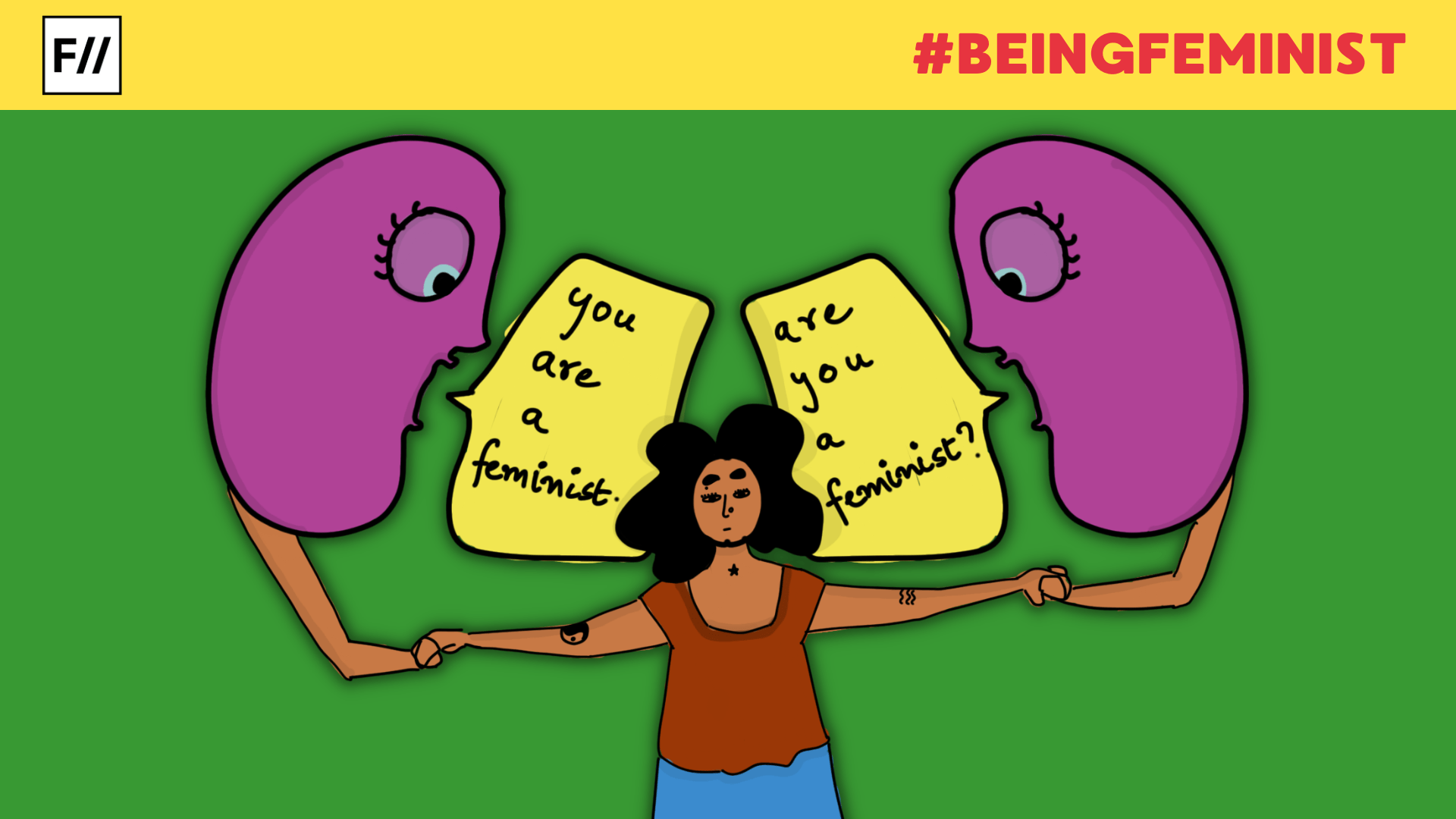

The year was 2016. I remember walking back to my bus after school with two of my friends. One of them announced rather boldly that she identified as a feminist and the other agreed immediately. I mulled the word over in my head for a moment. I had heard it of course. It came up from time to time on my mother’s WhatsApp forwards or the odd book I would read.

Feminists were loud and brash; argumentative hotheads with loud opinions. Sure, I thought women and men should be equals, but was I a feminist? Was I someone who could even be loud and opinionated? No. And so I kept quiet that evening, waiting for the conversation to segue into safer pastures. This was probably no different from the countless after-school conversations I had with several of my peers, but for some reason, it has stuck with me.

Growing up, you don’t immediately recognise that your world is inherently patriarchal because it is woven into the very fabric of the world that you inhabit. It is in the way mothers wake up an hour before the sun has risen, it is in the way the men eat first at family lunches while the women eat later on a soiled table, it is in the way sports teachers assign frisbee to girls and football to boys and never the other way around. You don’t think too much about the whys of it when you’re living in this bubble.

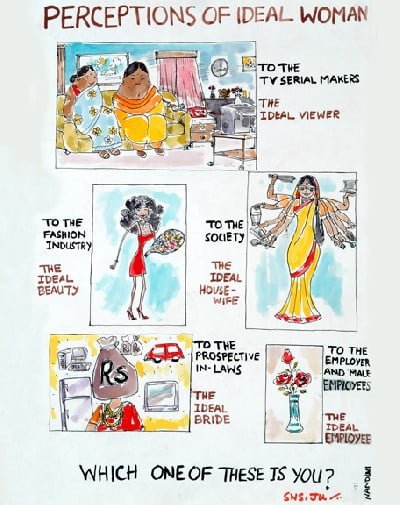

I think I started to pick up on these differences around Class 10. I remember very distinctly reading about the sexual division of labour in my textbook, there was this picture of a woman with ten arms, each hand clutching a household item; a jhaadu, a pochcha, a bucket, a spoon. I dug up my old pol-science box and spotted a small box next to it that housed a definition — Feminist: A woman or a man who believes in equal rights and opportunities for men and women.

It was such a small box, most teachers would have glossed right over it in classes. To give credit where credit was due though, this was probably when I became familiar with the term and what it really stood for rather than just the negative connotations it frequently generated in mainstream discourse. As I grew up, my awareness of this inequity between the genders was heightened too. I was suddenly made hyper-aware of the things I had grown up taking for granted.

At school, I picked up on a strange pattern I had not before. Even though me and a boy in my class would have consistent academic records, our teacher would berate him for his low scores. She would remind him of his potential, that he was “gifted,” and that he should try better next time. My low scores, on the other hand, would be chalked up to my not working hard enough.

Retrospectively, this was a recurring pattern in most of the classes I had been a part of — the academically excellent boys had a natural inclination towards the sciences, they were gifted whereas the girls who did well were “hard-working.” At the time, I was caught off guard by this understanding because it brought these biases from books and internet articles to my doorstep, or rather my classroom.

After Class 10, I would go on to join and withdraw from several coaching centres for medical and engineering entrance preparations. In the end, none were perfect for me as I ended up pursuing a degree in humanities. I had varied experiences at these coaching centres, the one running theme being the extremely toxic hustle culture; misogyny and casual sexism being part and parcel of it.

One of the teachers my mother and I visited, impressed with my grades, declared that I should be a doctor. He heard my mother out as she explained to him that I preferred mathematics rather than biology, and how I was more inclined towards maths-heavy engineering rather than medicine. He nodded his head, before continuing to tell us how girls are more “suited,” to be doctors. Despite my disinterest, he would continue to bring up the matter of biology tuition for as long as I studied there.

At another centre, I studied the restrictions placed on girls were amped up to a whole different level. For one, segregation of the genders was considered a matter of utmost importance for the students to be more “focused.” I was told by a teacher to stop wearing my hair loose and to braid it up for classes. The same teacher pulled aside one of my friends and her to stop wearing her cut-offs and sleeveless blouses (The boys will stare at you! Please dress appropriately). I was quite shaken by their demands because these were things not even my family would stop me from doing.

Despite my quiet frustration and anger, I was quick to conform while my friend on the other hand went on to wear her cut-offs for a week, each day ending with a promise to dress appropriately tomorrow. When I would ask her why she bothered with the fuss, she would shrug her shoulders as if she couldn’t care less. This continued till her mother was called up and asked to monitor her wardrobe choices.

My anger though present was repressed. I would turn it over in my head sometimes, quiet thoughts that I would voice to my mother in the privacy of our house, conversations I would share with my friends in those breaks between classes. Always thought of, pondered over, yet never acted upon. Though never spelt out in as many words, it was always understood that to thrive in this cutthroat academic atmosphere you have to lay low, not question the status quo, and play within the system rather than against it. I was never quite bold enough to stand up to my teachers and risk being seen as “that feminist girl.” But eventually, the system drained me; keeping my head down and carrying on with my work seemed less and less appealing.

Even when an institution is outwardly welcoming to female participants, there remains a difference in the way they treat women. I was always reminded of the fact that I was occupying a male space and that my being in that position was an allowance granted to me by the hegemonically patriarchal coaching system.

In order to reap the benefits of this position and the place granted to me, I had to play by their rules. I could choose but only from within the predetermined choices laid out in front of me. I could wear what I wanted to as long as they were loose fitting and appropriately covered, I could learn whatever I wanted to as long as I learned what my feminine brain was hardwired to handle.

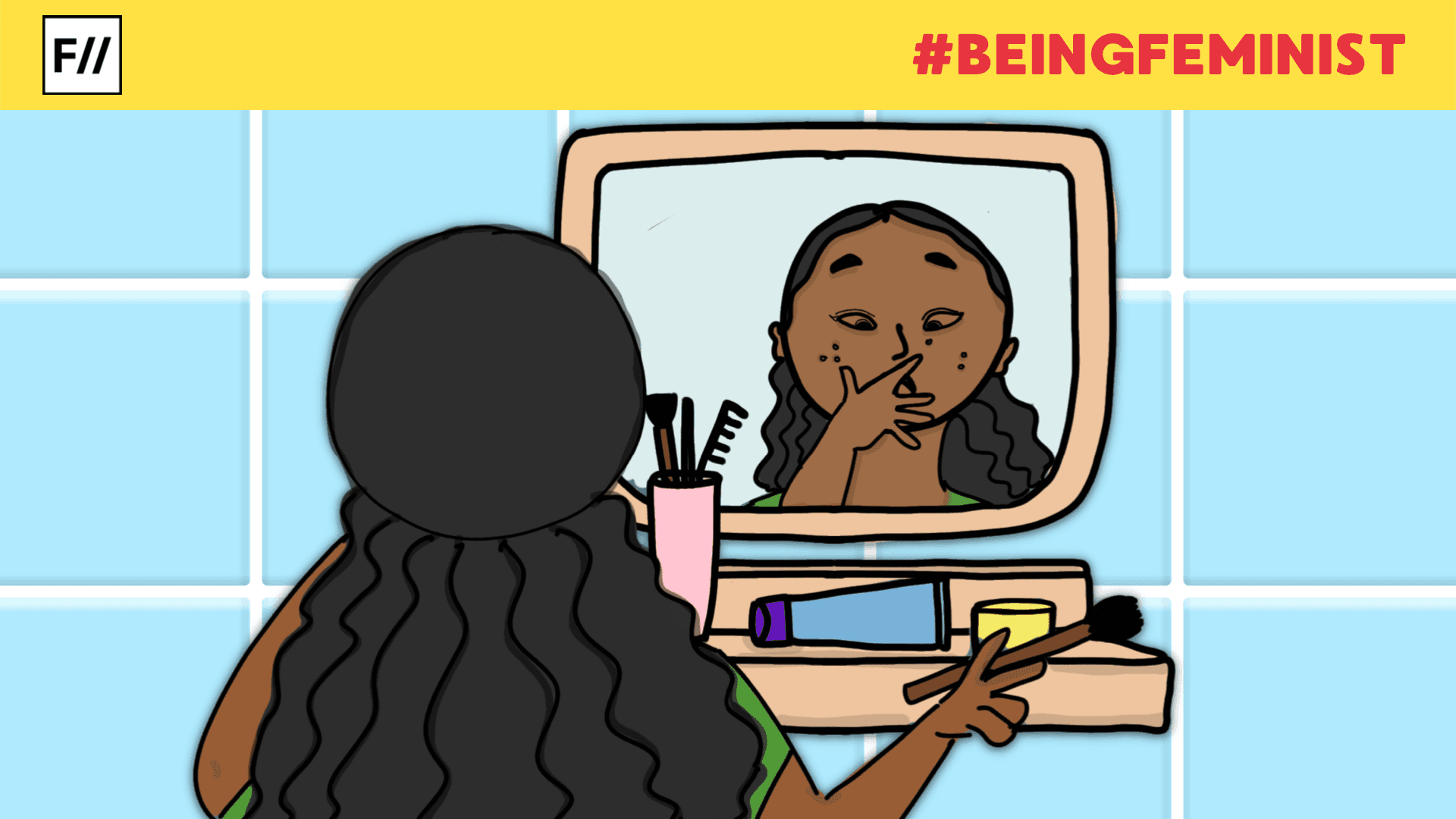

I am guilty of shaving my arms and wondering whether I actually do it for myself or if I do it because I have been conditioned to view smooth, hairless skin as desirable. I am still figuring out my identity as a feminist, but I’ve realised that being a feminist is not a destination in itself but a process of bettering yourself and broadening your understanding of what it means to be a feminist.

The institutional sexism that I encountered was couched within the outwardly feminist nature of the institution. The restrictions placed on young girls were cloaked under the guise of necessity; refusal to cooperate with the system was threatened with the failure of academic excellence.

I am not sure if it was because of the particular environment that I was situated in or because I had suddenly become more cognisant of the vast inequity between the genders, but this was the time I really understood the importance of the women’s movement; that it was beyond the confines of a small box in the corner of a high-school Political Science textbook.

That it was more than an abstract concept to be studied and pondered over, that it was something pulsating and alive that can be applied to my life. You only need to look around yourself, your family, your friends, your school, and your workplace to understand why you need to be a feminist.

I am not a perfect person, and so by extension, I am not a perfect feminist either. There have been times when I have let things carry on as they were instead of challenging the status quo but there have always been times since then when I’ve had the courage to say no; when I’ve questioned the hegemonic sexism I’ve found within my own home.

I am guilty of shaving my arms and wondering whether I actually do it for myself or if I do it because I have been conditioned to view smooth, hairless skin as desirable. I am still figuring out my identity as a feminist, but I’ve realised that being a feminist is not a destination in itself but a process of bettering yourself and broadening your understanding of what it means to be a feminist.

About the author(s)

Keerthana (she/her) is a third-year English Literature student at St. Stephen’s College, Delhi University. She is interested in analysing art and pop culture through feminist and other sociocultural theories. She enjoys literature, music, films and the occasional cricket match.