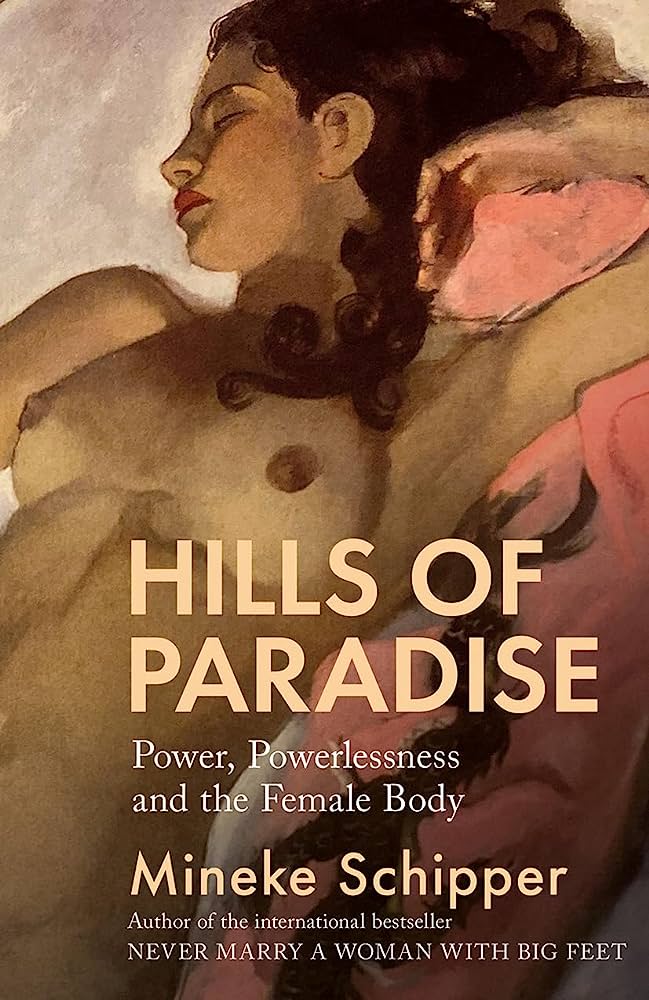

The fascination with locating origin points has been a common trend in many areas of academic inquiry. Feminists have tried to localise a historical instance to demarcate the beginnings of a patriarchal society. Theologians and historians have deeply inquired into the origins of human existence. Theories have abounded to answer both of these persistent questions and yet no definitive answer seems to come forth. Within this space of doubt, the newly released Hills of Paradise, authored by Dutch cultural anthropologist and academician, Dr Mineke Schipper, becomes an interesting answer for both.

In an expert manoeuvre, Dr Mineke Schipper juxtaposes the question of human existence with that of a patriarchal society by examining myths and origin stories arising from different regions and cultures. Using tools of comparative analysis, she attempts to draw out the similarities within these narratives to expose common themes of insecurity as a result of sexual differences.

The prodigal woman and Hills of Paradise

In literary theory, especially within psychoanalysis, the figure of the woman is often portrayed to be the figure of the ‘lack.’ Freud figured women as simply men without penises, and because of this so-called lack, he introduced the concept of penis envy. Much of psychoanalysis accounted for female behaviour based on this principle— that the woman acted out of envy toward her male counterparts, for she was explicitly aware that he possessed something she did not.

Most of male aggression and patriarchal control can be accounted for by male insecurity to lack the ability to procreate. Women, as bearers and incubators of progeny, become what Schipper calls the “gateway of life.” While copulation is a private activity, pregnancy and delivery are not.

Sexual differences, however, go both ways. What women lack, men possess and what men lack, women possess. To exemplify this, Dr Mineke Schipper introduces the concept of womb envy. Most male aggression and patriarchal control can be accounted for by male insecurity to lack the ability to procreate. Women, as bearers and incubators of progeny, become what Schipper calls the “gateway of life.” While copulation is a private activity, pregnancy and delivery are not.

This directly links women to acts of productivity, while men become more silent actors. This pattern began to replicate in other spheres of life too. Prehistorically, says Dr Mineke Schipper, the invention of agriculture has largely been associated with women, who then became the figure of plenitude and fertility. This is replicated in myths and cultural beliefs about local pantheons as well. It was more likely for a female god to be associated with agriculture, fertility and procreation than a male counterpart.

Womb envy, however, began to change this. The evolution of the monotheistic, male God took over the function of creation— at least in the case of the Abrahamic religions. In other cultures too, the male creator God replaced the mother Goddess. Origin myths began to award life-creating status to male gods instead, thereby reversing the power structure that came with it. The inherent assumption remained vested in the fact that the origin was superior to the result: if the creator was male, then men made in ‘His,’ reflection automatically became superior. Take, for example, one of the most well-known origin myths: the story of Adam and Eve.

Eve continues to be associated with the first Sin, and a fall from Paradise. In such a manoeuvre, the roles that men and women occupied in the ‘natural,’ order of life were interchanged via narrative techniques.

As the myth was told and re-told, Eve became less and less a creation of God, with Adam now ‘giving birth,’ to the First Woman instead. Eve continues to be associated with the first Sin, and a fall from Paradise. In such a manoeuvre, the roles that men and women occupied in the ‘natural,’ order of life were interchanged via narrative techniques. Myths from other cultures such as India, China and regions of Africa also revealed similar patterns. Men had successfully stolen the monopoly of women over the creation of new life.

In this analysing of myths and cultural stories of origin, Dr Schipper was able to successfully point at the deeper implication of it all. The anxiety of sexual differences had resulted in a consequent power difference: if men could not own ‘womanly,’ organs of procreation, then perhaps the next best thing was to own the women themselves.

Male control over female sexuality now extended into control over access to space, arenas of life, body parts, organs and so on and so forth until the figure of the woman came to be understood only in terms of the man. A masculine framing was essential to understanding the concept of womanhood. This is a phenomenon that continues to sustain itself in today’s day and age as well. Laura Mulvey talks about how women come to embody an attitude of “to-be-looked-at-ness,” where the subject decidedly remains masculine.

History in the (myth) making

The power structure of this passivity on the part of women, and activity on the part of men has been a consequence of storytelling and myth-making that put men on the forefront. However, such myths and legends come to be narrated as a result of patriarchal beliefs in the first place. The two are trapped in a self-sustaining cycle where a question of origination is rather chicken-or-egg.

Rather than merely trying to answer where the origins of patriarchy lie, therefore, Dr Mineke Schipper complicates the reader’s understanding of the importance of an origin point in the first place. The past and the present inherently feed into each other. That is to say, the formation of society in the past has a direct bearing on the structures embedded into society in the present.

Dr Schippher reveals how the symbol of the vulva shrouded in mystery, becomes both, a figure of plenitude as well as a protective symbol of threat. Womb envy then, extended as far as to say that those who bore the power of bestowing life, also had the power of taking it away. To counteract this insecurity, the need for male dominance further increased in a compensatory manner— solely men could stake a claim on other spheres of life whether educational, artistic, philosophical or scientific.

At the same time, however, the past can only be accessed via a lens of understanding that is rooted in the present. In such an academic inquiry, the interpretation of the past is sure to be influenced by the biases of the present. Origin stories and myths will be told and re-told with modifications that best fit to support and even sustain the power structures of the epoch.

The male construction of female sexuality projects onto women a contradictory ideal of nurturing, maternal figures of plenitude while simultaneously seductive, threatening and ravenous. Dr Schippher reveals how the symbol of the vulva shrouded in mystery, becomes both, a figure of plenitude as well as a protective symbol of threat. Womb envy then, extended as far as to say that those who bore the power of bestowing life, also had the power of taking it away. To counteract this insecurity, the need for male dominance further increased in a compensatory manner— solely men could stake a claim on other spheres of life whether educational, artistic, philosophical or scientific. Women were, and are, actively separated from the public sphere, with their docile presence in the domestic sphere tied to matters of honour and chastity.

Towards an indifference to difference

Even today, women who occupy space traditionally deemed male territory are culturally required to ascribe masculine traits to themselves. Dr Mineke Schipper demonstrates how curvy and voluptuous feminine bodies are only acceptable in the domestic space. The public sector requires women to occupy the least amount of space they can, possibly even masquerading as men instead. These shrouded stereotypes continue to exist in today’s world where many seem under the impression that feminism is no longer required to be an active movement.

In coming to modern-day phenomena, Dr Mineke Schipper spends a brief time discussing the #MeToo movement. She talks about how solidarity can create hope, and how awareness becomes essential to breaking stereotypes. At the same time, however, her perspective displays a more nuanced understanding. She explains how a position of victimisation can be tantalising, but how it does no good to the collective displacement of gender structures as they exist today. To perpetuate women as mere subjects to male aggression only furthers the easy distinction of men as wielders of power, and women as bodies of powerlessness.

To escape the power structures that constantly figure women as the underdogs with no one rooting for them, women need to actively and radically snatch power away. Hills of Paradise becomes a premium academic work that can help push women towards affirmative action. Easy to read, and minus the academic jargon that usually features such work, Dr Schipper’s supreme narrative style completely draws the reader in, aptly alternating between thorough analysis, literary theory and mythology from around the world.

To really appreciate the message of the Hills of Paradise, however, the reader needs to be well-versed in a nuanced understanding of history that doesn’t attempt to further indulge in the blame game between the sexes, but rather an undertaking to expose the anxieties that lead to power vacuums because of sexual difference.

The biology that marks men as separate from women continues to exist, although the lines between them are perhaps more murky than one might think. Instead of a definite focus on what differentiates them, however, Dr Mineke Schipper calls for a “dialogue,” that attempts to look beyond these differences, going as far as to find solidarity despite these differences.

On that note, we would like to respond with where Dr Schipper ends:

“We can but dream.”

References

Schipper, Mineke. “Hills of Paradise.” Speaking Tiger Books, 2023, India.

About the author(s)

Ananya is a 20-year-old student at Ashoka University, in love with all things literature. She makes great decisions when it comes to movie nights but with life? Not so much.

Wow,great theory .Truly seems like an interesting read.Man and women are just born with biological difference,but that should not mark their areas for respect,superiority or powerplay.Well articulated.

Thanks, Anya, for reading my book Hills of Paradise and sharing with readers your thoughts and comments with this well-written and solid review!

“Anxieties that cause power vacuums due to sexual differences”.. it’s the kind of observation that stays!!

It is important foe even men to read such literature!

Very well written . Well expressed. Keep it up ananya