‘‘ḳhusrav’ ‘nijām’ ke bal-bal jaiye

mohe suhāgan kīnhīñ re mose naināñ milāy ke‘

‘I give my whole life to you Oh, Nijam,

You have made me your bride, by just a glance.‘

Amir Khusrou

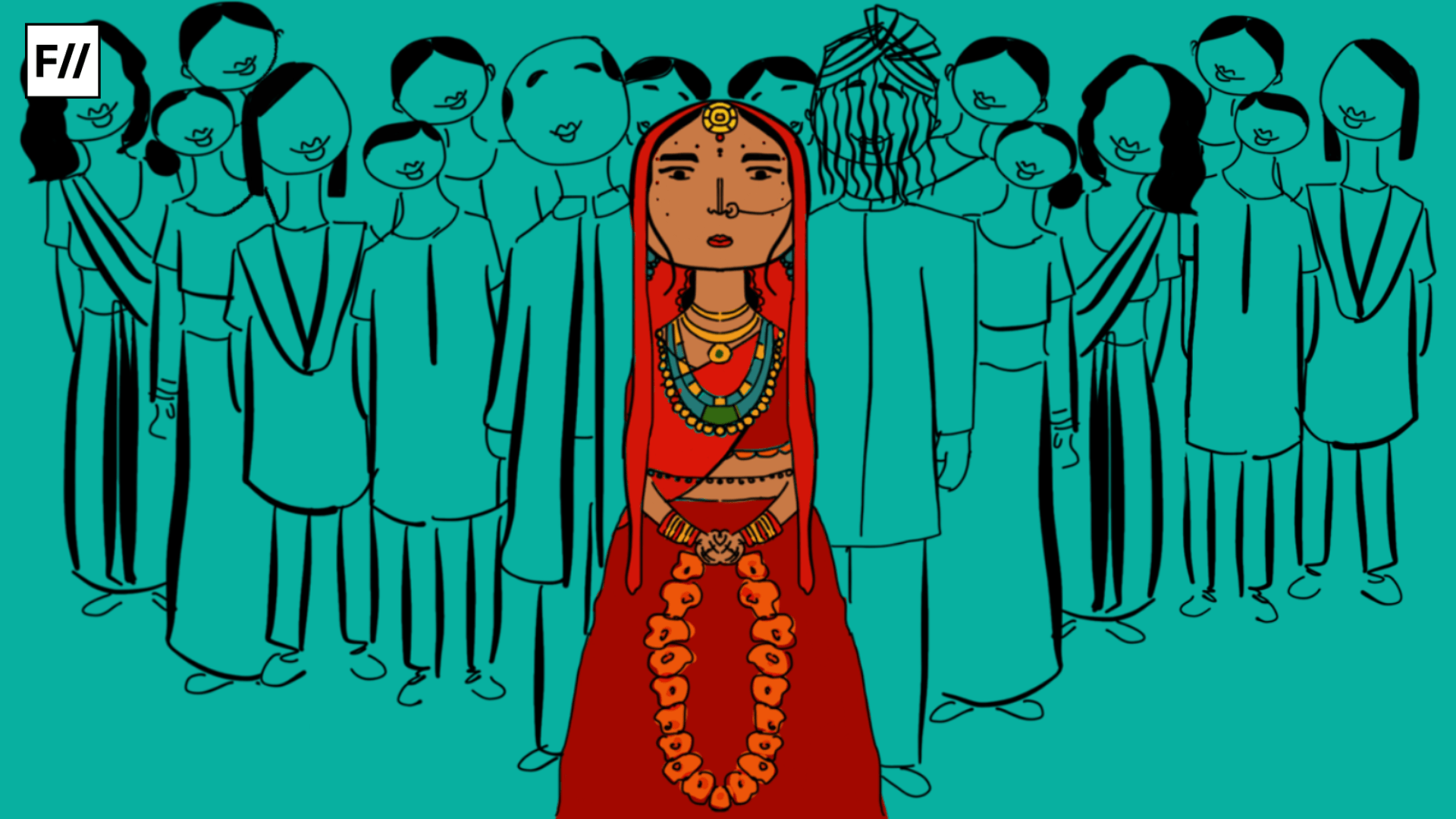

The aforementioned quote is a verse by Amir Khusrou, a celebrated 14th century Sufi poet of India, which he dedicated to his spiritual mentor, Nizamuddin Auliya. While this kalam ‘Chaap Tilak Sab Cheenli‘ has swept into the popular culture in the form of Qawwalis, what goes unheard is the subtle undertone of queerness. Though this is not to claim that the poet Amir Khusrou was homosexual. However the frank use of romantic imagery to express affection and admiration towards one male figure from another cannot be overlooked.

Though this is not to claim that the poet Amir Khusrou was homosexual, however the frank use of romantic imagery to express affection and admiration towards one male figure from another cannot be overlooked

If a similar discourse takes place between the same sexes in the modern heteronormative society replete with homophobia, regardless of the presence of homosexual intentions or not, they would be shunned for their “immoral,” “unnatural,” “sinful” and “west-imported” behaviour by the people who strongly oppose the legalisation of same sex- marriages. But these labels and the arguments behind these labels are nothing unprecedented and are pseudo-intellectual claims to mask the underlying paranoia and anxiety which follows the initiation of every social reform.

Marriage- not a definite institution

The opponents of same sex marriage view marriage as a definite institution. But much to their disappointment, the definition of a legitimate marriage has varied among communities historically. Parameters like caste, religion, race, sex, and degree of consanguinity have always governed the social choice of who is an acceptable spouse.

When Keshub Chandra Sen filed a petition in 1868 to the Government of India for a law to secure the legality of Brahmo marriages, the colonial government responded with a form of civil marriage law. Brahmo Samaj was a monotheistic Hindu sect that had accommodated unorthodox practices like non-idolatrous worship, inter-caste marriages and even widow remarriages. Sen felt that their reformist practices rendered their marriages legally invalid under the Hindu law and threatened the inheritance rights of the children of Brahmo Samaj members. In response to the petition, Henry Maine, Law member of Governor-General’s Legislative Council, proposed ‘Native Marriage Bill’ which contained the provision for civil marriage for those who were not Christian and neither did they want to marry according to the Muslim, Hindu, Parsi, Buddhist or Jewish rites. Furthermore, the bill allowed only monogamous marriages, recognised inter-caste marriages and prescribed the minimum age for marriage 14 and 18 for women and men respectively.

Maine’s draft was met with huge opposition as it challenged the established socio-religious institutions. ‘Coorgs,’ an ethno-linguistic group who did not follow the rituals of Hindu religion, protested. The new law prohibited cross-cousin marriages on the grounds of consanguinity which was a customary practice among Coorgs. But cousin marriages do not enjoy approval in many parts of the world and are deemed to be “incestuous”, hence “sinful”. Marriage between first cousins is prohibited in South Korea, Philippines, China and almost in half of the U.S. states. In India, such marriages are restricted under the Hindu law while permitted under the Muslim law. These legal boundaries not only reflect the contradictory public notions of “marriage” between nations but also within a single nation.

Furthermore , recognition of inter-caste marriages was unacceptable to many including the Coorgs. Babu Kali Prasanna Banarji, one of the petitioners against the passing of such a law, argues that the issue of intercaste unions would be looked upon by Hindus ‘with hatred, and treated as bastards and never be allowed to remain within the pale of the Hindu community.’ Acceptance of inter-caste marriages still largely remains an unfulfilled dream as the India Human Development Survey in 2011 shows only about 5% of Indian marriages are inter-caste. Despite having obtained legal status, inter-caste couples continue to face social stigma but it is undeniable that social acceptability of intercaste marriages have increased in comparison to the second half of the 19th century.

History is a witness to polygamous marriages, polyandrous marriages, monogamous marriages , child marriages , cousin marriages, widow remarriages, all sanctioned by socio-religious customs. Hence to define marriage as an immutable and consistent institution is to be historically incorrect and socially oblivious. The berdaeche traditions of Native America and transgenerational same-sex unions in the samurai class of warriors in Japan are few of the practices which challenge the notion that marriage has always been between “a man and a woman”.

Homophobia- a Western import

Conservative narratives often rely on the idea that the strain of social change is induced by the corrupting influence of a foreign culture.

During the early Indian nationalist phase, the hatred against the colonial power was regarded as enough reason to oppose the social reforms by cultural revivalists without giving the substance of such reforms the consideration it deserved. The hatred against the highly exploitative colonial government is valid but uncontrolled abhorrence robbed the revivalists the ability to scrutinise their institutions and practices which did injustice to their own people.

The conservative narrative presents ‘homosexuality’ as a West-imported concept which is incompatible with the Indian culture. Religious rhetoric is further used to paint the West as a Satanic force ravaging through the land to dismantle the moral Indian society and fracture its virtuous social institutions. It is surprising that the opposers to the legalisation of same-sex marriage tend to forget is that homophobia is a Western import by the British colonisers to the extent that it strengthened the pre-existing strain of homophobia by introducing homophobic legislations.

In the second half of the 19th century, social purity campaigns dictated the discourses around sexual morality in Britain targeting the the ‘Great Social Evil’ of Victorian society i.e., prostitution specifically and non-procreative sexual activity broadly.

In the second half of the 19th century, social purity campaigns dictated the discourses around sexual morality in Britain targeting the the ‘Great Social Evil’ of Victorian society i.e., prostitution specifically and non-procreative sexual activity broadly. The debates in Britain crept into its colonies and in 1860, the Indian Law Commission headed by Lord Macaulay introduced Section 377 into the Indian Penal Code which punished sexual conduct ‘against the order of nature’. British viceroy Lord Elgin warned that British soldiers could succumb to ‘replicas of Sodom and Gomorrah‘ as they acquired the ‘special Oriental vices‘.

Colonisers saw the Indian society as sexually deviant and sought to reform its moral laxity by repressing Homoerotic Persian and Urdu literature and by brutally persecuting the Hijra community. The Criminal Tribes Act, 1971 introduced a category of ‘eunuchs’ who were registered if they were suspected of kidnapping or castrating children, or of committing offences under section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, or of abetting the commission of any of the said offences. Under Section 26 of the Act, the registered eunuchs could be arrested without warrant and be imprisoned for up to two years. They could face imprisonment if they just appeared in ‘female clothes’ at a public place with the intention of being seen from a public street or place.

Though the colonised lands eventually emerged as proud independent nations, versions of Section 377 continued to jeopardise the basic liberties of the previously colonised people. In 2018, Theresa May, the former Prime Minister of United Kingdom, expressed her deep regrets for Britain’s legacy of anti-gay laws and colonial homophobia saying, ‘I deeply regret both the fact that such laws were introduced, and the legacy of discrimination, violence and even death that persists today.’ Later that year, in Navtej Singh Johar v. Union Of India, on 6 September 2018, the five-judge Bench of the Supreme Court unanimously declared the law unconstitutional ‘in so far as it criminalises consensual sexual conduct between adults of the same sex‘.

The modern-day repugnance towards the idea of same-sex marriage is a remnant of barbarous colonial laws and callous Victorian attitude against homosexuality

It is difficult to trace the extent of prevalent homophobia in pre-colonial period with precision, but to completely deny any form of societal toleration towards homosexuality or to question the very existence of it is a self-deceiving argument. The modern-day homophobia and repugnance towards the idea of same-sex marriage is a remnant of barbarous colonial laws and callous Victorian attitude against homosexuality.

Marriage is perceived as a sacred institution and any attempt to meddle with it has always and will always receive immense reactions. But due to the multitudes of sacredness, the deviant categories outlaid are many a times contradictory and hence the judgemental notions like “unnatural”, “immoral” and “sinful” becomes ridiculous grounds to deprive certain marriages of their legal sanctity. The act of refusing to give same-sex marriages socio-legal sanctity by neglecting the Indian homosexual past and reducing this major human rights issue to a mere “Western propaganda” reeks of homophobia. In this way, the nervous conservative opposition has portrayed marriage as a closed system which has no space to accommodate any diversity. If such a narrow definition of marriage is to be accepted, no community will ever acknowledge marriages which do not follow its marriage rites. However, we do not find diverse communities of our nation condemning each other’s marriage as illegitimate. The Hindus acknowledge Muslim marriages and vice versa even in the presence of uncomfortable elements like cousin marriages. The conservative hypocrisy kicks only when legitimacy of same-sex marriage is debated. The struggle for legalisation of same-sex marriage is not a demand for full-hearted acceptance of homosexuality and same-sex unions but dignified acknowledgement of it, one step further than precolonial tolerance.

I appreciate the way the author skillfully delved into India’s intricate relationship with LGBTQ+ issues by incorporating history, culture, and contemporary attitudes into their narrative. What particularly caught my attention was the reference to Amir Khusrou’s poetry, subtly hinting at the historical presence of queerness in Indian society.Overall, the author has effectively called out the enduring impact of colonial-era homophobia and courageously challenged those persistent stereotypes. Keep up the excellent work!

I appreciate the way the author skillfully delved into India’s intricate relationship with LGBTQ+ issues by incorporating history, culture, and contemporary attitudes into their narrative. What particularly caught my attention was the reference to Amir Khusrou’s poetry, subtly hinting at the historical presence of queerness in Indian society. In essence, the author has effectively called out the enduring impact of homophobia and courageously challenged those persistent stereotypes. Keep up the excellent work!