Mental health has undeniably emerged as a mainstream topic of conversation in the 21st century. The field of psychology has reached high influence, with a rising number of individuals considering therapy and seeking professional assistance. In the realm of psychology and mental health, a profound realisation has emerged that personal struggles are not isolated occurrences but are intricately linked to the broader socio-political context. Recognising that mental health is a deeply political issue has become paramount, as it is profoundly influenced by power structures, societal norms, and policy decisions that shape our everyday lives.

Understanding this dynamic relationship between mental health and politics can serve as a powerful catalyst for driving positive political change. It encourages us to examine how political factors and social conditions impact mental well-being, fostering a more holistic and well-rounded approach to addressing mental health challenges.

Accessibility of mental health assistance

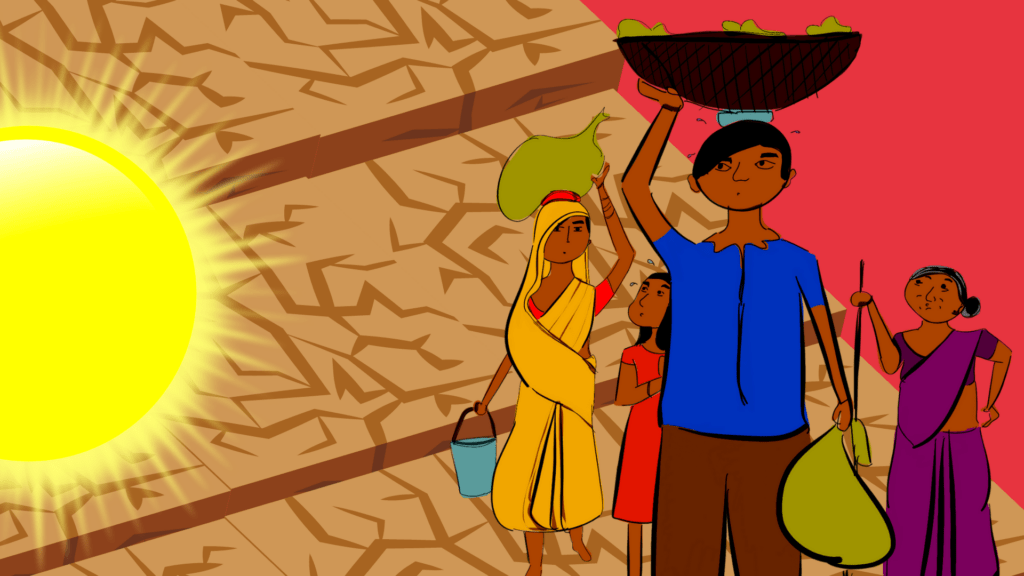

The accessibility of mental health assistance has long been a concerning issue. Unfortunately, a prevalent myth suggests that mental health is solely a concept of urban or Western societies, which is linked to broader socio-political contexts. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that mental health is a genuine concern affecting people worldwide.

Despite its significance, awareness and advocacy efforts often fail to reach marginalised and less-privileged sections of society. This, in turn, contributes to the misconception that mental health is an urban fallacy devoid of relevance in the real world.

Regrettably, the reality is that mental health accessibility has become a matter of class distinction. While mental health aid is readily available to the elite and privileged, it remains a far-fetched luxury for many others. This disparity in access highlights the pressing need for a more inclusive and equitable approach to mental health support, where all individuals, regardless of their background or socioeconomic status, can access the care they deserve.

Mental Health through Intersectionality

Understanding the impact of the outside world on mental health requires a fundamental grasp of intersectionality. The term “intersectionality,” describes how social categories including race, gender, class, sexual orientation, disability, and other aspects of identity are interrelated. The phrase emphasises how different categories interact and cross rather than existing in isolation, giving people who possess many marginalised identities the opportunity to have distinctive and overlapping experiences.

Mental health and intersectionality are inherently interconnected, in tandem with each other, and genuine progress in mental health advocacy can only be achieved when viewed through the lenses of political awareness and trauma-informed allyship. Embracing an intersectional perspective allows us to recognise the complex interplay of various social identities and experiences that shape an individual’s mental state.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

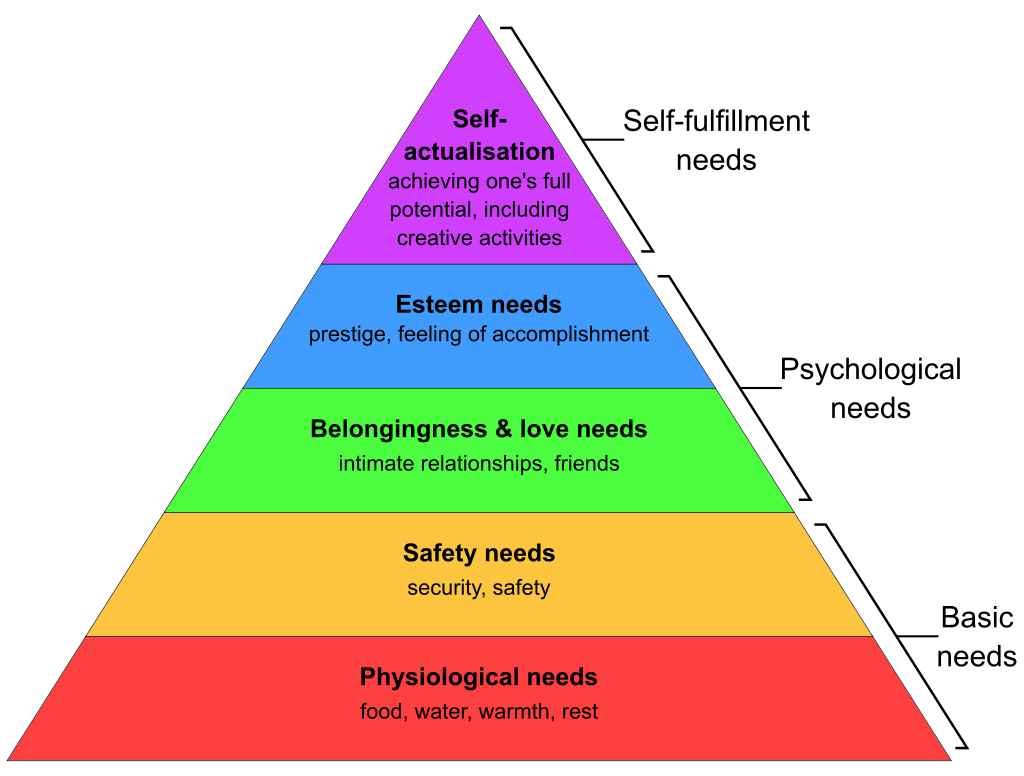

The dialogue on intersectionality and mental health remains unfulfilled without bringing Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs into the political narrative. Abraham Maslow proposed the psychological theory known as Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in 1943. According to this theory, needs are arranged hierarchically and are arranged into a pyramid with five tiers.

Maslow asserts that people are driven to satisfy these requirements in a particular order, starting with the most fundamental demands at the base of the pyramid and working their way up when the lower needs are met. The five tiers, in order, are Physiological Needs (food, shelter, water, sleep for survival), Safety Needs, Love and Belongingness Needs, Esteem Needs and Self Actualisation. Unless the first two or three needs are met, mental health and well-being cannot be achieved. And it is a fact in the case of most people, that these prior needs are never met.

For people with marginalised identities, including SCs, STs, OBCs and minorities in India, non-white (especially African Americans) and Native Americans in America, Palestinians, Kashmiris, people with disabilities, cis women, gender minorities and economically weaker individuals; mental health becomes a secondary or tertiary factor of concern. It may never even be a factor of concern for them at all, since their fundamental needs and fundamental rights (and human rights) are not secured. For them, survival is of supreme importance than mental health.

Even though they do suffer from psychological trauma, their testimony lies in the survivors of tragedies like the partition of British India, the Holocaust, the Nakba of Palestine, Slavery, World Wars and wars in Iraq, and Afghanistan among many others. To this day, the survivors of these tragedies suffer from chronic psychological traumas which affect them physically and mentally.

The survivors of political and historical tragedies are the major examples of people with politically induced trauma. However, to this day, marginalised people also face trauma inflicted by others who come from a place of prejudice, daily.

Psychological trauma on the marginalised

In the context of the intersectionality of mental health, it is important to acknowledge that in addition to conventionally recognised trauma, marginalised people face politically motivated trauma as well. The psychological trauma inflicted on marginalized individuals can occur in the form of conservative thinking, microaggressions, discrimination and exposure to bigotry. This trauma seldom is acknowledged by mental health advocates and professionals.

They may experience psychological distress due to conservative ideologies prevalent in society which perpetuate hate against them. These ideologies can be harmful stereotypes and stigmatisation, making it challenging for individuals to express their authentic selves without fear of judgment or rejection. An example of conservative thinking can be misogyny stemming from the roots of patriarchy, beauty stereotypes stemming from racism and colourism etcetera. Women brought up in conservative households often face psychological trauma as well as psychological conditioning.

Microaggressions are subtle, everyday verbal or nonverbal behaviours that communicate derogatory or negative messages. These seemingly minor interactions can accumulate over time, leading to heightened stress and emotional strain. These subtle behaviours include stereotypical jokes disguised under the garb of dark humour, insensitive comments, passive aggressiveness, and remarks on the “exoticness,” of a person who’s different.

People from marginalised communities also often face discrimination and prejudice, whether in education, employment, healthcare, or various social settings. Experiencing discrimination can lead to feelings of powerlessness, anger, and frustration, all of which can have profound effects on mental health. For instance, Dalit women are often denied entry into hospitals, even when they are in labour, which results in their deaths. There is proven research which indicates that there is a hiring bias towards Muslim women in jobs in India. People belonging to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes often face discrimination.

Constant exposure to bigotry and hate speech, whether in person or through media and social platforms, can be deeply distressing and traumatizing for marginalised individuals. This exposure can reinforce feelings of vulnerability and insecurity.

For example, hate speech against the Muslim community is at its peak in India, whether online or in real life. Many instances of hate speech in real life have been reported. The hate speech includes calls for violence against the Muslim community, calls for (sexually) assaulting its women and calls for dismantling the holy sites of the community. It has also been reported that the country which has produced the most amount of hateful content online towards the Muslim community in India. These are examples of bigotry and hate speech which can be psychologically distressing to marginalised communities.

Need for an inclusive and affirmative therapy space

Effective mental health therapy can be significantly hampered by judgmental therapists and misdiagnosis, particularly for members of marginalised communities and genders. Some therapists in traditional mental health settings could have prejudiced views or a lack of awareness of different identities, which could result in judgmental attitudes and a potential misdiagnosis of their client’s problems.

Therapists who have stigmatising beliefs or personal biases may unintentionally make their patients feel uncomfortable and invalidated. Such dispositions might obstruct honest conversation and limit how thoroughly clients can share their emotions and experiences. Being judged or misunderstood can exacerbate mental health conditions and discourage clients from seeking more help.

Misdiagnosis happens when mental health practitioners overlook the particular difficulties faced by people from disadvantaged backgrounds. Inappropriate treatment regimens that might not address the underlying causes of distress might result from symptoms associated with cultural, social, or identity-related variables being mistakenly assigned to common mental health problems.

To address the concerns related to the mental health of the members belonging to the queer community, a practice of queer affirmative therapy has emerged in the domain of psychology. Diverse sexual orientations and gender identities are validated and supported by the queer-positive treatment method in this practice. It entails fostering a welcoming environment where queer clients can express their worries without fear of judgement.

Individuals from marginalised communities might have a more inclusive and compassionate therapeutic journey by obtaining treatment from affirmative therapists. By recognising and affirming the different identities and experiences of their clients, these therapists play a significant part in removing obstacles to mental health care and fostering mental well-being.

Additionally, affirmative therapy’s secure environment encourages patients to examine their mental health issues honestly, which has a good impact on their recovery process. However, merely focusing on diverse identities is not adequate for creating a world where mental health services are inclusive and available to everyone. There is a need to make mental health services affordable and in some cases, even free. These services need to reach rural areas, refugee camps, slum areas, dependent women and people from lowered classes and castes.

The motto for inclusivity in the realm of mental health is, “Personal is Political,” indeed. The adage “personal is political,” was first used by feminists in the 1960s and 1970s, and it has subsequently spread to other social justice movements as a core idea. It highlights how human challenges and issues are profoundly influenced by political, social, and cultural contexts, demonstrating the connection between personal experiences and larger societal institutions. It becomes clear that mental health is not just an individual concern but is also significantly influenced by external variables, such as institutional disparities, discrimination, and societal norms when we apply the idea of “personal is political,” to mental health.

Recognising the political character of mental health necessitates comprehensive approaches to mental health care on a societal level. This entails tackling structural disparities, eliminating stigma, and advocating for policies that give everyone, especially marginalised communities, priority when it comes to mental health support.