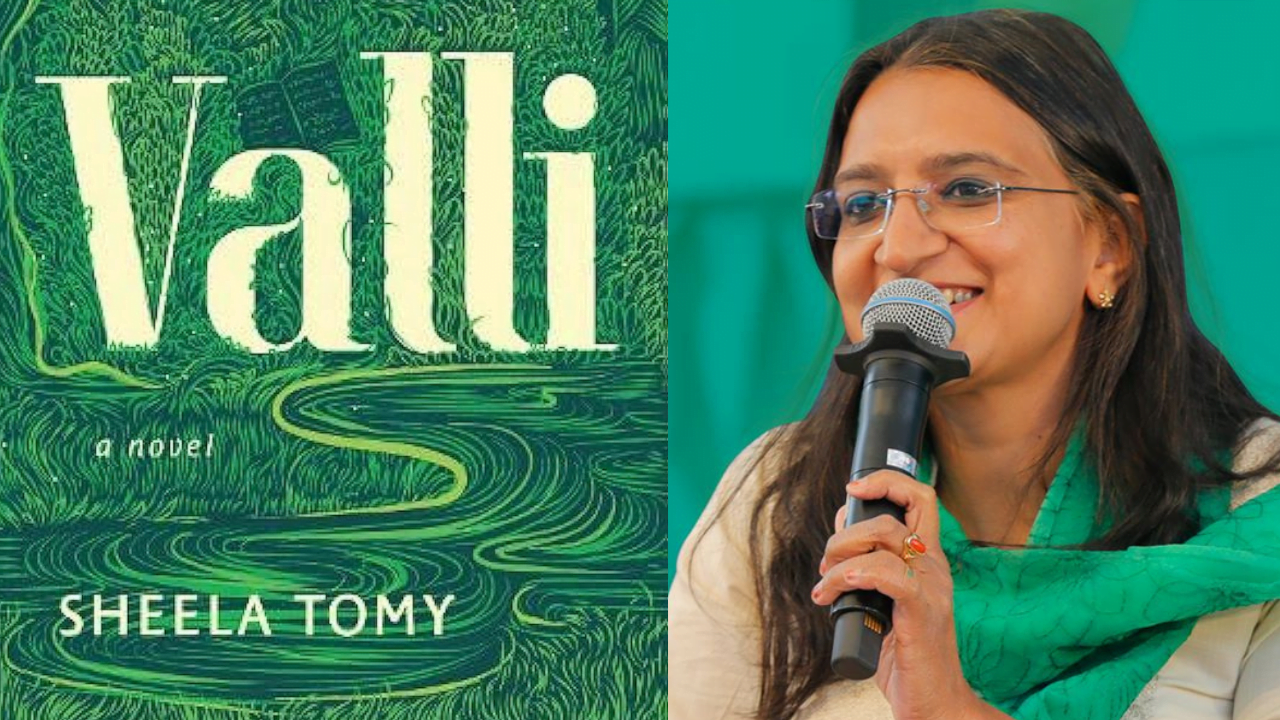

Valli is the debut novel of Malayalam author, Sheela Tomy and it was translated into English by the award-winning translator, Jayasree Kalathil. The novel received the Cherukad Award for Malayalam Literature in 2020 and the English translation was shortlisted for the JCB Prize for Literature in 2022.

Valli unfolds in the idyllic town of Kalluvayal, nestled deep within the Western Ghats. It tells the tale of the migrants who settled in what was then known as Bayalnadu (the land of rice paddies, now called Wayanad), as well as the Adivasis, who are the true keepers of the woods. Entwined with the land, the book becomes an insightful analysis of environmental and social justice.

The novel spans four generations and switches narrative voices throughout. We meet Tessa, who is the daughter of Susan and the granddaughter of Sara and Thommichan. We are introduced to Kalluvayal when Sara and Thommichan migrate to the forests of Wayanad as eloping newlyweds in the 70s.

A wide range of interesting characters are introduced by the author, each of whom adds complexity and nuance to the story. But the main character is the forest, a repository of enigmas and legends. The aboriginal people naturally love and respect nature but the novel bears witness to how some outsiders also develop a connection with it by discovering its mysteries and comforts.

Valli’s positionality and portrayal of Adivasis

Valli chronicles Kalluvayal from the times it was a deep and dense forest to the times when it turned into a concrete jungle with its river dry and flora and fauna almost destroyed. Throughout the chronicle, we bear witness to the injustices done to the Adivasis of Wayanad and their continued resistance against various entities to preserve their way of life.

In our era of political consciousness where we are paying attention to ‘who gets to talk about who,’ more than ever, Valli might be an excellent example of a novel that’s aware of its positionality and deals with an oppressed community with respect and care they deserve (without gaining a saviour complex, that is).

While talking about the novel’s positionality, it’s important to note that Sheela Tomy herself was born and brought up in a Christian migrant household in Wayanad. The fact that she’s writing Valli having lived in Wayanad herself and it’s filled with things she’s seen, touched, smelled and felt lends it a certain level of credibility. In her author’s note, she describes her research for the novel and she says, “I went into Adivasi settlements in an attempt to understand their lives and histories at least in a small way, worried about how much justice my words could do to their stories as I wrote them.”

The Adivasi characters in her novel are highly detailed and the gaze is never problematic. She seems to have handled responsibly talking about the Wayanadan Adivasis without othering them and their way of life.

However, what makes Valli a truly politically conscious text is the incorporation of the Paniya language throughout. Kalathil notes, in the translator’s note, that the Paniya language is part of the South Dravidian languages which have no script and in Kerala, Paniya words are usually written using the Malayalam script. In the original, Tomy made sure the characters from the Paniyar community spoke in their language instead of standard Malayalam.

Similarly, the translated version also renders Paniya words phonetically in English before explaining what they mean. This exercise of letting readers try to sound out these foreign words for themselves is equally powerful and delightful. Furthermore, this conscious effort from both the author and the translator to retain this language without a script in their writing again lends credibility to them as non-Adivasi individuals writing about the community.

Valli captures the lives of the Wayanadan Adivasis in vivid detail, from their folklore and gods to their medicine and funeral rites. However, it also captures them as painfully human people who have loved and lost just as the rest of us. They’re constantly battling one thing or the other throughout the novel; first, it’s the jenmis (landowners) refusing to give them wages for their labour, second, it’s the merchants trying to illegally cut down trees from their forest and much later, it’s the exploitative tourism businesses that displaces them and encroaches on forest land. Their resilience in the face of adversity can only be admired.

The prose is also written in such a way that the community in Kalluvayal, both Adivasi and some outsiders, is intricately connected with the forest. The forest lives and breathes in them and when they suffer, it suffers with them and vice versa. This mutual exchange and unbreakable bond helps the readers feel the pain of the forests and its people more acutely.

For instance, when Rukku tells Basavan, “Ninaaku bayiluchelina mana, Basava,” (You smell like the mud of the fields, Basava), he replies that he would die when he lost that smell. Later, when Basavan does die, she wonders if he died because the fields and forests that were so innate to him as a person had disappeared from Kalluvayal. As a reader then, you don’t just grieve for Basavan but for the entirety of Kalluvayal.

Even towards the end of the novel, we see how the Adivasis hold on to the remaining forests. Kelumooppan, the aged community chief of the Adivasis who is almost a hundred years old by the end of the story, continues to live in a hermit cave in the forest despite the government providing living quarters for the community elsewhere. He tells Tessa and Thommichan who had come to visit him that he’d rather die in the forest. This moment in the story is a reflection of reality where many communities that get displaced due to ‘developmental,’ or ‘tourism,’ projects don’t get rehabilitated properly.

We arrogantly expect forest-dwellers like Kelumooppan to quietly live away from the forests, which make up their livelihood and everything they know as we slowly destroy their homes. They won’t let it go that easily. They fought for ‘valli,’ (a share of the crop) before and they fight for ‘valli,’ (the earth itself) still.

Additionally, it’s also a deeply feminist novel lending its focus to various women starting from Unniyachi, a Devadasi of folklore to the modern women of Kalluvayal like Susan and Tessa. The novel can easily be categorised under ecofeminist literature. Furthermore, when the forests of Kalluvayal take root in Tessa’s mind after her mother’s death, the readers are left with several important questions. What are we leaving our children to inherit? Are we teaching them to value the lives of forests, rivers, animals and birds? Are we teaching them to maintain the balance or be careless as to warrant the wrath of nature?

Overall, Valli stays true to its dedication in the beginning stating, “For forests ravages by fire, For people rendered voiceless, For languages without scripts.” In all the ways it counts, the novel is an account of history, that is focused on the people (otherwise deemed ‘the other,’) and their struggles. Given the widespread erasure of Adivasi culture and languages and things like the new Forest Conservation Act Amendment Bill, 2023 coming into play, ‘Valli’ will no doubt go down as a very relevant and critical piece of writing of our times.

About the author(s)

Sharanya Gopalakrishnan is a recently graduated journalism student from Flame University. She

loves reading and watching cringe TV shows. She hopes to publish her own novel someday.