In present times, it is important to decode whether the body positivity movement only caters to upper caste and able bodies to understand social perceptions and notions. There is a reel on Instagram that illustrates, ‘reservation se seat mil sakti hai, genetics nahin‘ (reservation can give a seat, not genetics). It is nonsensical to assume this because caste has nothing to do with biological traits; it is just a social construct. It is not natural, but socially accepted just to enhance and maintain categorisation.

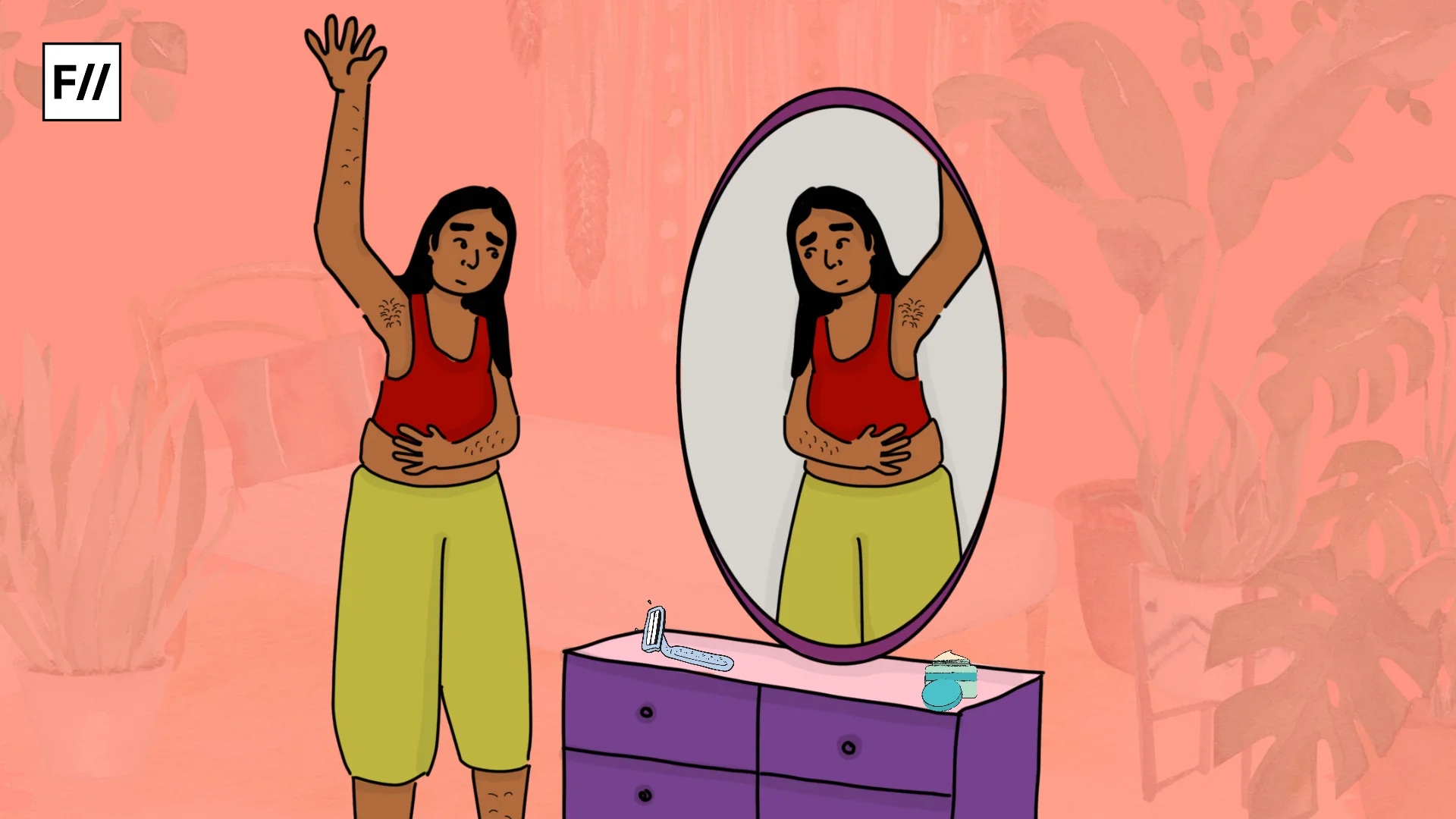

Before scrutinising this topic, it is significant to start with understanding the body positivity movement and its importance in the mainstream. In a general perception, it is a social movement that deals with accepting all body types, sizes and shapes.

The movement began with fat rights activism and later faced criticism

The body positivity movement can be traced back to the fat rights movement in 1969 when a young engineer in New York, Bill Fabrey, was enraged at the way the world looked at his fat wife. A couple of years earlier, he had come across an article by a fat man named Lew Louderbach and his analysis of fat people being treated in an unfair manner. He was eventually successful in forming the National Association to Aid Fat Americans, which is today known to the world as the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance or NAAFA.

This white mainstream movement separated itself from people of colour; it failed to take their voices into consideration. It was a belief among white activists that Black communities and other people of colour accepted fat people, so they did not want fat activism. Another criticism the movement faces is that people misunderstand it as encouraging obesity. Although it encourages inclusion, it is believed that ‘the body positivity movement is contributing to being obese.’

The movement helps create a healthy body image that, according to the Office on Women’s Health, means feeling good about one’s body. Having a negative body image triggers higher risks for mental conditions and eating disorders.

It is worthwhile to note, according to a research analysis from the National Library of Medicine, the body positivity movement has different meanings. On the one hand, it is white-centric, with its association with young, lean, and able-bodied people. On the other hand, this movement challenges patriarchal, neoliberal, capitalist and colonial ideologies of a “good body”. There is no doubt that the movement was organised against body-related oppressions, but fitness industries and popular culture are held responsible for appropriating and commodifying the body positivity movement to marginalise people of diverse races, disabled people, and other minorities.

There is no doubt that the movement was organised against body-related oppressions, but fitness industries and popular culture are held responsible for appropriating and commodifying the body positivity movement to marginalise people of diverse races, disabled people, and other minorities.

Sonia Renee Taylor, a body rights activist, asserts, ‘If the movement is positive for some bodies, it is not a body positive movement.’ It has been demonstrated that ‘white feminism’ and its association with the body positive movement fails to challenge the oppression people face based on gender, religion and race; it is seen as making efforts only for white people.

Likewise, when it comes to Indian society where caste as a social phenomenon is accountable for categorising people in terms of body image or representation, body positivity is associated with upper castes and able-bodied people.

High body standards for upper castes is a social construct, not an inherent biological trait

As it has been mentioned earlier, there is a reel on Instagram where it asserts reservation can provide a seat, not genetics; it is a casteist remark on social media which associates a good body image with privileged castes. To support this argument, there is a 2022 research analysis published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), authored by experts affiliated with the Research Institute for Compassionate Economics.

The research institute is a non-profit organisation that focuses on health and well-being in India and presents the findings that Dalits, Adivasis and Muslims have a lower life expectancy rate than upper-caste Hindus. Although the life expectancy of Muslims is almost a year lower than that of upper-caste Hindus, Adivasis have a four-year gap, whereas Dalits have more than a three-year gap. It is interesting to note that there are social disadvantages behind this gap, not biological traits.

Likewise, when it comes to associating body positivity with upper castes and able-bodied people, it is just another social construct; it does not have a biological basis. In India, fair skin is preferred among the upper castes of Hindu and Muslim religious communities. Although there can be various factors behind preferring light skin- such as caste system, European colonialism, capitalism, and globalisation, light skin is considered social capital.

The Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB) scientists in Hyderabad revealed through their research that genetic differences and the caste system are the main reasons for the region-wise variation in the skin colour of Indians. It revealed that the caste system has a tremendous influence on skin pigmentation. The team had taken into consideration 1,825 individuals who belonged to 52 diverse groups in India. The study said that the migration of people into India and admixture of people, according to Dr. Thangaraj, were the reasons for skin variations among ethnic groups and social categories in Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. For instance, the Brahmins in UP have the fairest Skin, while the Manjhis have the darkest skin. Endogamy plays an important role in preserving genetic traits.

Among Muslims, inter-caste marriages are rare to avoid mixture and preserve genetic traits. In India, there is so much obsession with fair skin that it is recognised as a status symbol.

Among Muslims, inter-caste marriages are rare to avoid mixture and preserve genetic traits. In India, there is so much obsession with fair skin that it is recognised as a status symbol. Beauty is defined by the caste and class systems. The upper-caste dominant notion fixes high beauty standards for upper-caste people, such as lighter skin, thinness and tall structure, while lower castes are considered dark-skinned.

No intersectional approach is followed in mainstream body positivity movements

When it comes to defining mainstream body positivity, it excludes marginalised people based on caste and class. There is a lack of an intersectional approach being followed in mainstream body positivity. It focuses on general beauty standards but does not consider caste-based body-related oppressions. The deep-rooted caste system makes people even more vulnerable to skin colour-based discrimination. The discrimination favours fair skin, which is often considered a marker of dignity, purity, and high social status, whereas dark skin is associated with inferiority, labour and subjugation. This skin colour-based gap is visible in cultural norms, languages and visual representations in India. For instance, the word ‘chandala‘, which refers to the community related to the occupation of disposing corpses, is used to define ugliness.

The concept of intersectionality is even significant to understand people facing discrimination based on the intersection of disability, caste and class. Disabled people are one of the most neglected minorities in India whose plight becomes worse with caste and class. Disability is considered as a “defect” in people who are born with them, and their disabilities are linked to the concept of “Karma” in past life. It means people who are born with disabilities or into low castes did so because they led an unsanctified life in the past.

Henceforth, low-caste disabled people remain excluded from mainstream body positivity movements. In order to trace social structures that maintain high body standards for upper castes, there is a need to opt for an intersectional approach. Although the body positivity movement was intended, for the first time, to challenge structural discrimination for black liberation, it lost its importance over time when capitalists and privileged people got involved into this to focus on aesthetic self-love and loving one’s body without understanding politics and embedded social structures.

There are expensive commercial brands that promote products to lighten skin complexion, body fitness industries to tone body muscles, and other products to enhance facial features which are used by upper-caste and class people.

In mainstream body positivity, certain bodies are supposed to be empowered, not all. There are expensive commercial brands that promote products to lighten skin complexion, body fitness industries to tone body muscles, and other products to enhance facial features which are used by upper-caste and class people. Due to capitalist intervention, there has been a shift from focusing on body rights to selling products for enhancements. In the midst of all this, marginalised castes and disabled people remain invisible in mainstream body positivity movements.

About the author(s)

Nashra Rehman finds her profound interest in addressing the plight of Muslim women and their unappreciated marginalisation. Her focus remains on bringing a novel argument to life.