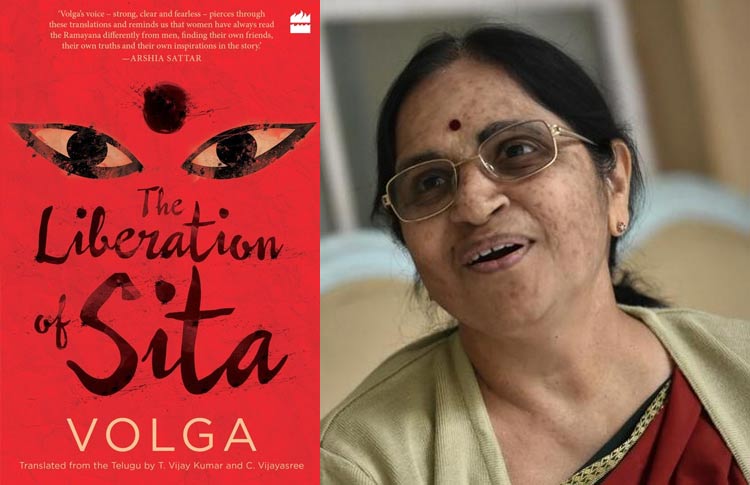

“Classical Telugu literature has had a liberal tradition of questioning mythology”, says Volga, aka Popuri Lalitha Kumari. Her highly acclaimed work, The Liberation of Sita has also garnered criticism from certain fronts, mostly threats to not temper with mythology. But Volga has carried on with this inquisitive, thoughtful tradition of Telugu literature, showing Sita and other overlooked female characters from Ramayana in a different light – from their own perspectives, displaying their perceptions about the men in their lives.

Ramayana does not tell us the woes of these women – Ahallya, Surpnakha, Renuka Devi, Urmila, and many more, but Volga does it, picturesquely at that. Her work has been awarded with the Laadli Media Award for Gender Sensitivity in Fiction for 2017.

As one progresses through the first few pages of the book, Sita’s confusion and her uneasiness on meeting a lot of these other women who were abandoned by their husbands/sons becomes oddly intriguing. Volga takes us through Sita’s innocent questions about the injustice done to these women to Rama’s confounded silence on all of them. At this moment, one can draw parallels with her questions today, with the feminist movement’s challenges to the continuance of a patriarchal society, trying to shake up the very notions that systemically subjugate women.

One of the major contributions of this book is it has promoted the idea of ‘sisterhood’, much less known than the oft-celebrated idea of brotherhood. Usually described as jealous and resenting other women, Volga’s depiction of women is a break from this absurd myth. Sita meets some of these women – Surpnakha for instance, and immediately empathises with them, equating her own hardships like trial by fire with tribulations of others. Volga’s description of Surpnakha portrays her in a way that one cannot help but feel overwhelmed.

Usually described as jealous and resenting other women, Volga’s depiction of women is a break from this absurd myth and promotes sisterhood.

A woman from a demon clan working at the orders of her brother, learns to love herself the way she is. Surpnakha’s face, being disfigured by Lakshmana led her into discovering her that there is more than one way in which a woman could love beyond her physical beauty – through her creations of art, her belongingness with nature and just realising her worth as a complete individual. Surpnakha while being lonely in the tangible world, was content through the true realisation of the self.

This theme of meditation, a spiritual connect women find within themselves after being humiliated and ousted by men in their lives is a common streak throughout the book and words fail to describe how beautifully Volga has depicted all their journeys. Consider Ahalya. Being fraudulently led by Indra to sleep with her in the guise of her husband, she is labelled as unchaste and ousted by Gautama, despite being innocent, for being violated by a man without her consent.

Also read: 7 Times The Women In Mahabharata Got Their Due

Ram describes her as a ‘characterless’ woman which infuriates Sita when she comes to know of the truth. Her curiosity takes her to Ahalya’s hut in the forest, where she’s baffled by her incongruity to Sita’s perception of Rama, a noble, amazing man. Volga then takes us to Sita’s trial that was made to prove her chastity, where she decrypts every word said by Ahalya that day – men have made so many rules for women to own their sexuality that it’s never about these women, only about men who cannot tolerate this chastity being ‘robbed’ by other men.

Renuka Devi’s experience is particularly appalling on so many levels. She was ordered to be beheaded by her husband and her son does so at his father’s insistence . This was because Renuka Devi apparently looked at a man for which she was labelled as unchaste by her husband. Only when her husband’s fury subsided, he ordered his son Parsurama to stop with the beheading, but scarring Renuka Devi for life as she was betrayed by the two men she had dedicated her life for.

Renuka tells Sita that it is totally futile for women to make men the centre of their lives, because she had been deceived by both her husband and son, on a ridiculous pretext, and women remain the subjects of male apathy no matter what. She talks about her wifehood, motherhood being besmirched by these men who thought they were the flag bearers of dharma. Instead, women must strive to find their own identities, to do something worthwhile with their own lives. That’s fulfilment. Sita too realises this later in her life when her sons wish to leave her to live with their father, Ram.

One of the reasons why Volga wrote this book was to make Ramayana relevant in a modern context where women have explicitly started to no longer tolerate intellectual or physical oppression to conform to any mythological impressions of femininity. She understands that epics like Ramayana have been used by upper castes to subjugate women for several centuries. Moreover, women being the battle grounds for men to wage their wars is a common underpinning in our important mythological stories.

Men fighting to protect their wives, waging wars for ‘restoring their wives’ honour’, then putting them through trials to prove their loyalty is a reality even today, in different ways. Sita was well-educated, and the legend says she could easily lift a bow nobody else could. However, an epitome of perfection, daughter of mother earth, still reduced to her role as a wife, spent an eternity in the service of her husband, only to realise that she could never be happy in the mortal world. When her husband abandoned her, she dedicated her life in raising their sons, only to hear them praise their father’s valour and nobility and leave her to live with him.

She understands that epics like Ramayana have been used by upper castes to subjugate women for several centuries.

As per Volga, all these experiences ultimately helped Sita to liberate herself from whatever she went through in the mortal world. However, it’s also important to understand that a woman’s liberation is not merely in her disentanglement from the material world. While spirituality is equally important, a feminist interpretation can also include a woman’s life being stable and filled with contentment no matter what her experiences were, in the very society that secludes her for being ‘unchaste’.

The author’s depiction of Ram is quite interesting as well. Towards the end, Ram is seen being miserable, for he couldn’t be himself. The shackles of Arya Dharma around him remained a barrier in his liberation from these worldly roles that never made him happy.

Also read: We Owe Shurpanakha And Other Mythological Women An Apology

But while he remained and chose to live a life of a dutiful, noble king, Sita found her deliverance away from these identities. At last, she tells Rama – “I am the daughter of Earth, Rama. I have realised who I am. The whole universe belongs to me. I don’t lack anything. I am the daughter of Earth.”

Featured Image Source: Indian Women Blog

About the author(s)

Mehak Bajpai is a lawyer in early twenties. She’s pursuing her career in legal academia at National Law University Delhi. She specializes in criminal law, constitutional law and strongly feels about gender issues.

IS THIS THE INSTANT OF LIBERATION OF SITA ?

Sita called Rama an Impotent Pansy.dindooohindoo

Book II : Ayodhya Kanda – Book Of Ayodhya Chapter[Sarga] 30

किम् त्वा अमन्यत वैदेहः पिता मे मिथिला अधिपः | राम जामातरम् प्राप्य स्त्रियम् पुरुष विग्रहम् || २-३०-३

“What my father, the king of Mithila belonging to the country of Videha, think of himself having got as so-in-law you, a woman having the form of a man?”

अनृतम् बल लोको अयम् अज्ञानात् यद्द् हि वक्ष्यति | तेजो न अस्ति परम् रामे तपति इव दिवा करे || २-३०-४