For a long time, women were excluded from formal education system thereby restricting them from expressing their opinions through their writing that would reflect their experiences of oppression. Women were victims not only of the everyday forms of violence in the household but they were also denied of equal political rights in the public sphere.

During the late colonial period however, these discriminations of patriarchal domination were brought into light by the social reformers in Bengal and Maharashtra. The Indian elites began to be amalgamated into a middle class which sought to transform itself by organising campaigns against various caste based discrimination, child marriage, sati, purdah system etc. They took up the responsibility on behalf of the women of abolishing the orthodox prejudices and restructuring the society.

However, such appropriations of the lives of women were not only flawed, but they often led to the preservation of patriarchy rather than its abolishment. 19th century reformers believed that the difference between the sexes was such that their roles, functions, aims and desires were different. Later, they asserted that such differences mustn’t be a reason for the subjugation of women. Conversely, however, they used this same “difference” to portray women as “mothers of the nation” or as “goddesses” for their nationalist propaganda. Such perspectives were emphasised not only to provide momentum to the nationalist movement but also to guard the institutions of family and religion from any crisis or dysfunction.

The denial of educational opportunities to women in turn helped men acquire cultural capital over the years thereby gradually facilitating them to become more eligible to read, write, interpret and understand the changes occurring in and around them. Their cultural capital also helped these upper castes, middle class men to attain social and economic capital which created a gap between the social positions of the two genders. They became objects of knowledge, of language and of power that took charge of advancing the Women’s movement and were not ready to pass over the control that they commanded over the lives of women.

Rassundari Devi’s “Amar Jibon (1876)” is a text that marked the historic event of publishing a woman’s autobiography which challenged patriarchy as early as the 19th century Bengal. She did not receive any formal education, since literate women were looked down upon at that period of time.

However, there are accounts of women who challenged such patriarchal orders and produced texts in order to motivate and mobilise women to come together and resist against the gender norms. Rassundari Devi’s “Amar Jibon (1876)” is a text that marked the historic event of publishing a woman’s autobiography which challenged patriarchy as early as the 19th century Bengal. She did not receive any formal education, since literate women were looked down upon at that period of time. However, that could not forbid her to read and write. Since then, various other female writers had started lettering their experiences into texts that would help mobilise women against the oppressive gender roles.

The criticism by the colonialists against the orthodox and traditional Indian culture focused largely on the treatment of women. The nationalists, especially the middle class reformers, hence brought a “new patriarchy” into existence that claimed to be different not only from the traditional Indian order but also dissimilar from the Western culture. It began the construction of a “new woman” typically belonging to the urban, middle class families who was exposed to these changes that were occurring in the educational system of the society. This “new woman” was educated but not westernized, but neither was she the oppressed object of traditional patriarchy that denied educational opportunities and a space in the public sphere.

Autonomous organisations were formed and forms of activism were constructed with approaches that were written and conceptualised by women. But even though the leadership was passed on to women, it was still the privileged, urban, upper caste, middle class women who took the charge to decide the course of action of their rebellion against oppression. It failed to capture the oppression that Dalit women, rural women or the Muslim women faced during that time thereby resulting to an inadequate representation of the subaltern.

These issues, which were giving birth to differences between women in that period of time and failing to assemble women from all classes, castes, creeds, cultures, ethnicities and religions, still persist to exist even in the contemporary industrialised, democratic India. The state, even after seven decades of independence has been unable to ensure equal opportunities for women, which would guarantee an unbiased representation of women in politics, movements and in other spheres of everyday life. However, contemporary feminists have tried to include the subaltern in their literature as well as their movements and are continuously making an effort to bring forward the voices that were repressed through centuries.

Writing: A Form Of Protest

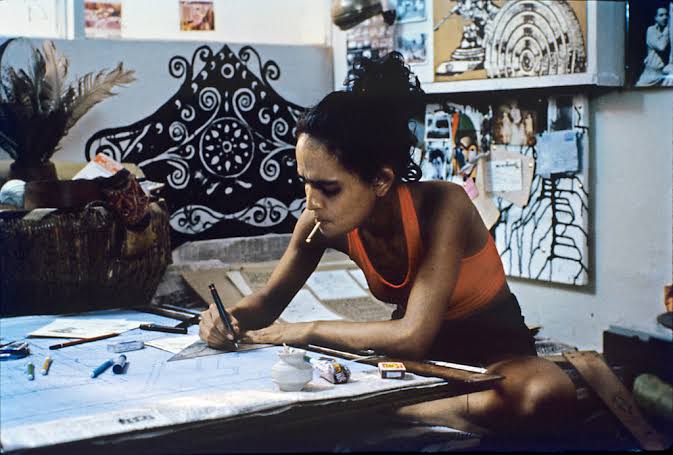

When Mahasweta Devi started writing she was 13 and India was still colonized. She is now popularly known as one of the foremost post-colonial feminists who signify a “rare union of revolutionary creativity and radical social action”. Her work traces not only the history of resistance by women against the colonial rule but they also reflect of her incessant battle against the government machinery that exploited and oppressed the subaltern groups in many parts of India since independence. Her sympathetic portrayal of the subordination of women and the violence afflicted on them by various masculine structures, both in public (State) and private (Family) domains of the society had spread a consciousness of the need for a struggle to build a movement for women in India.

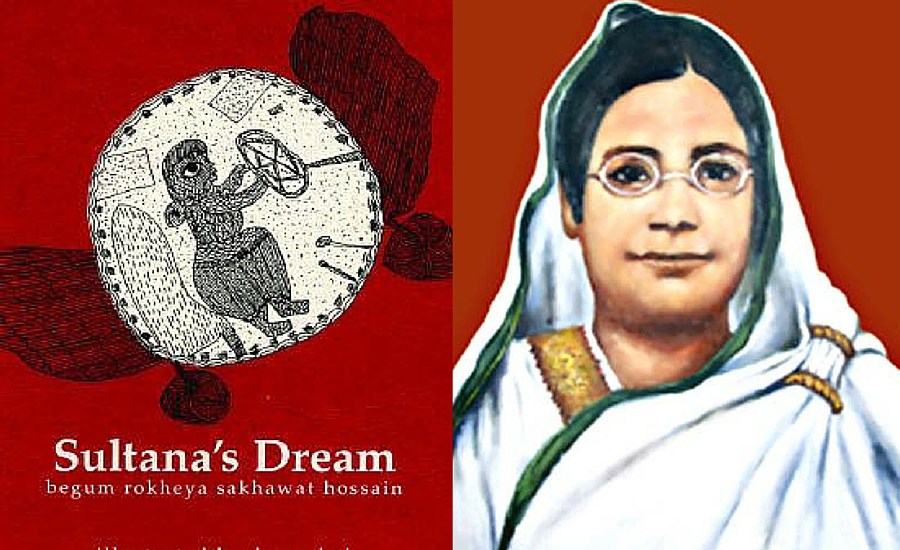

Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, a Bengali writer and activist, popularly considered as the pioneer of Islamic feminism in India wrote a sci-fi utopian novella called “Sultana’s Dream (1905)” which attempted to include the Muslim women within the feminist philosophy challenging the bias of Women’s movement that simply concerned itself with issues about the Hindu women thereby ignoring diverse voices and opinions. After a decade, in the year 1916, the Begum of Bhopal founded the All India Muslim Conference whose primary objective was to impart education to women and fight against Muslim forms of patriarchal order and gender roles. Much later, Ismat Chugtai became a powerful voice in Urdu literature and fought for the freedom of speech when she was convicted for homoeroticism and her “fearless explorations of feminine sexuality” in her book “Lihaaf (1942)”.

Apart from Bengal, Maharashtra too witnessed the production of a great variety of feminist literature. Marathi female writers such as Tarabai Shinde, Pandita Ramabai and Anandibai Joshi have produced writings that have critiqued colonialism as well as provided profundity to the Women’s protests within the movement by challenging religious oppression, brahmanical order and male domination.

Image Source: Akshadhara

Marathi female writers such as Tarabai Shinde, Pandita Ramabai and Anandibai Joshi have produced writings that have critiqued colonialism as well as provided profundity to the Women’s protests within the movement by challenging religious oppression, brahmanical order and male domination.

Various writers from different parts of the country started penning down their experiences as women or as nationalists demanding equal recognition in the movement for Independence. Texts written by Cornelia Sorabji and Sarojini Naidu reflect such ideas that claimed spaces for women, be it ideological or political. However, a major breakthrough occurred in the Women’s movement when the Committee on the Status of Women in India published a report called “Towards Equality” in the year 1974 which dealt with various themes and issues concerning the conditions of women in India.

Image Source: Lincoln’s Inn

The last three decades witnessed a huge growth in the number of feminist writings written both around the Indian context keeping them in constant dialogue with the feminist developments worldwide. Writers such as Kamla Bhasin, Ritu Menon, Vandana Shiva, Arundhati Roy contributed an enormous range of perspectives to several matters from a feminist standpoint. In the domain of journalism and media too, women started entering such spaces which earlier were dominated by men.

Image Source: The Hindu

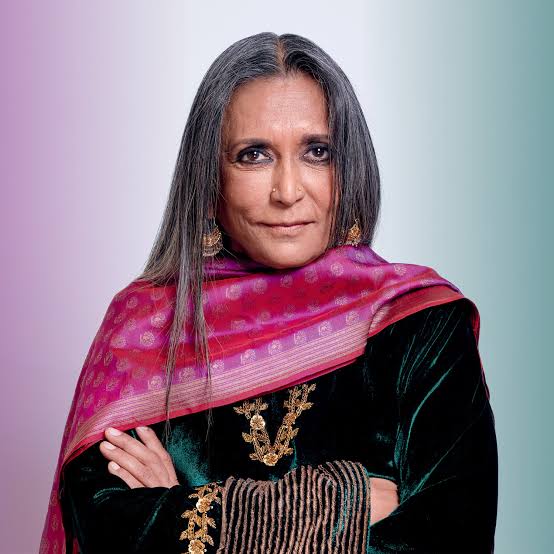

Women also entered into the Indian film industry and produced films that were based on issues regarding women’s sexuality, their oppression, their everyday struggles and their contribution in the society. Deepa Mehta’s “Fire (1998)”, a script based on homosexual relationship between two Hindu women produced an outrage from Hindu fundamentalist groups which led to various incidents of violence in the theatres as they attempted to shut down screenings of the film.

Image Source: Bay Street Bull

Also read: Writing From The Margins: Meet 6 Authors Who Are Women of Colour

Two decades later, the situation hasn’t changed much as even today films based on feminist scripts are banned by religious fanatics who constantly try to threaten such progressive ideas through means of political power or physical violence. This too happens when women speak up in social media about issues not only concerning to the Women, but also raise their voices against religious, caste based, ethnic atrocities in the country.

They fall victims to various episodes of verbal threatening in the form of rape threats or are even physically or sexually assaulted or even murdered by the orthodox, conservative groups. The harassment of Gurmehar Kaur and the murder of the journalist, Gauri Lankesh who resisted against various forces through their writings on their social media accounts, stand as examples of such ruthless violence against women by the Hindu fundamentalists even in the 21st century India thereby resulting in a setback to the Women’s movement in this country.

Conclusion

My knowledge about the contribution to literature by women is restricted to the works of Bengali or Maharashtrian writers since I was mostly exposed to them. It is also restricted to the works of women that were published and received a certain amount of recognition. However, there are various texts that were written but never received ample acknowledgement.

Also read: Why Have A Category Called “Women’s Writing” When There Is None For “Men’s Writing”?

There are also male writers, filmmakers, journalists who have contributed in the Women’s movement in India and have suffered the consequences of taking a standpoint for women through their writings. These limitations need to be addressed and written about in order to provide a more elaborate explanation as to how the act of writing can be revolutionary for movements.

Featured Image Source: The New York Times

About the author(s)

Pragya is a Master's Graduate in Sociology from Jawaharlal Nehru University. She works as the content editor at Feminism In India. She is also a ramen enthusiast, a hummus mother, a postcard hoarder and a wannabe cat lady. She still prefers writing on her notebooks, rather than on her laptop, but her job demands her to do just the opposite. Her favourite season is spring, and her alter ego is that of Mrs. Dalloway who said, "She would buy the flowers herself", in case no man ever buys her any!