An average Indian tends to look at Indian politics with a rather sceptical view, and Realpolitik makes it easier to understand why.

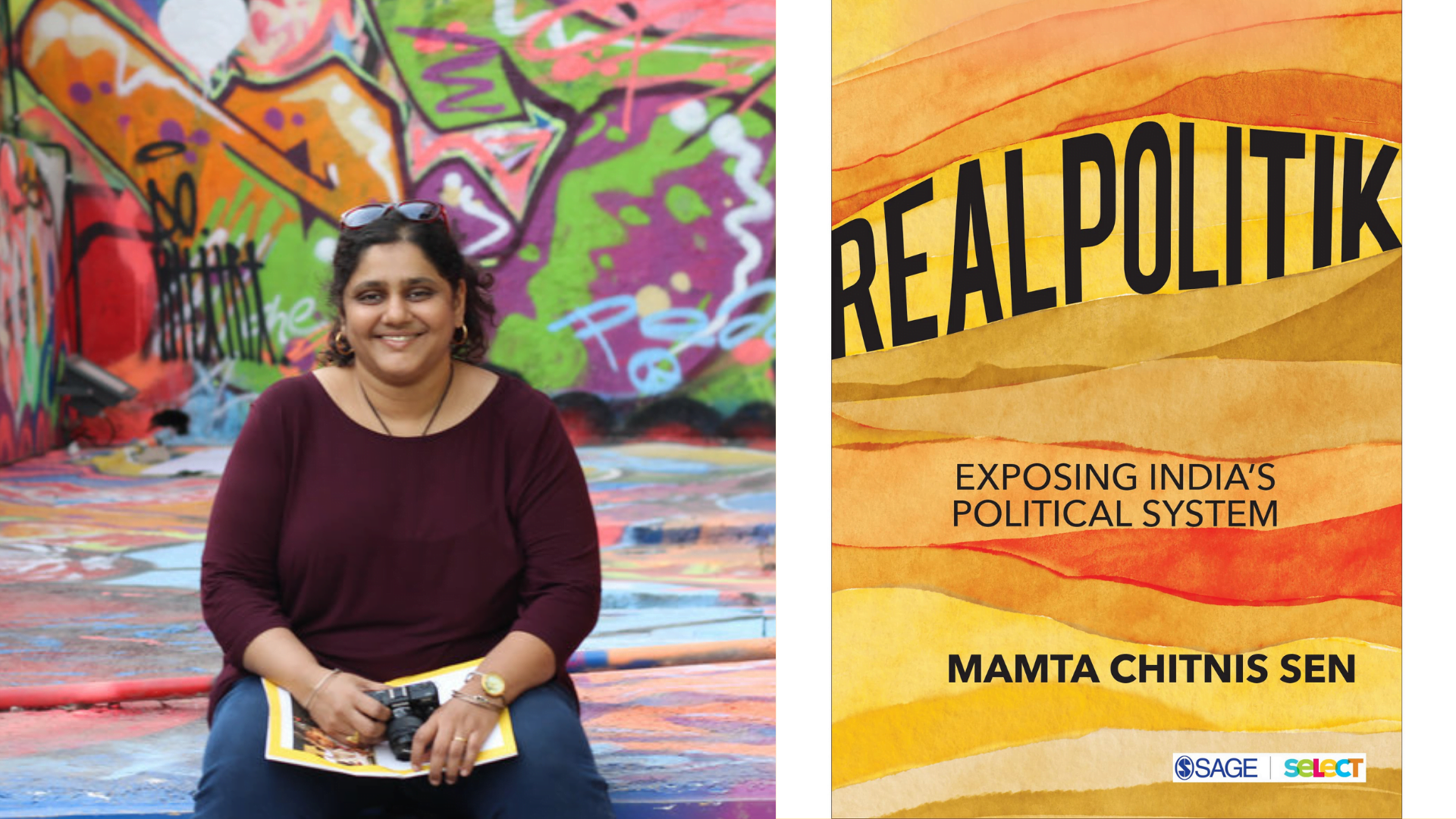

Mamta Chitnis Sen, through the course of her book Realpolitik: Exposing India’s Political System takes us on a journey where we get a holistic view of what it is like being actively involved in politics. While on one hand is the fact that all political parties have a specific ideology and all the members of a party quite automatically fall under it, we are also faced with the reality that party workers and leaders shift allegiance all the time; this blurs the lines between socialism and nationalism in the context of Indian politics.

While on one hand is the fact that all political parties have a specific ideology and all the members of a party quite automatically fall under it, in Realpolitik we are also faced with the reality that party workers and leaders shift allegiance all the time; this blurs the lines between socialism and nationalism in the context of Indian politics.

When we read Realpolitik, it becomes evident why: Politics is about power more than an ideology, who is hungry for it, and who is privileged enough to get it.

Money, Power, and Class

Politics is no different from any other sphere of the society.

Realpolitik paints a picture where we see foot soldiers of a political party doing all the legwork from putting up banners, handling social media, to giving statements; and it also has the testimonies, which would make one wonder in what ways are these efforts of a party worker rewarded, if at all. What Realpolitik also does is put us in the shoes of a grassroot worker, where we see several defining aspects of a party worker’s journey.

First, people can join politics for various reasons, and to participate in policy making is hardly ever one of them. Workers join a particular party because ‘their friends were joining it’, or ‘they were fascinated by a leader’ or ‘they were asked to do so, by a party or a person’ and so on. What is missing in all of these stories is the profound understanding of the importance of politics in those who are actually joining these parties.

Perhaps the people whose lives are most affected by politics, never find it possible to venture into it.

Second, while several people do mention ‘social work’ as the reason why they were drawn in the first place, the aspect of ideology or political leaning is missing in most people’s testimonies. What does seem apparent is the Hindutva aspect of right wing politics in India, and the fact that right wing political workers seem to like associating themselves with this ideology.

Third, whether or not a person rises up in the positions depends to a large extent on if they are financially sound, related to some big politician or if they belong to a politically active family. Realpolitik extensively draws the readers’ attention to these minute and intricate nuances of Indian politics, which are governed by money, power and class.

Reservation, Caste and the question of Inclusion

What Realpolitik calls “Vote Bank Tokenism” is the representation of a political system which has reservation and identity politics at its core, without actually taking cognisance of why they are etched in the first place. The book takes us on a journey where we see caste and religion based politics evolving over the decades, but never giving the leadership positions to the marginalised communities.

In the cases where Dalit leaders do end up in the office of Chief Minister, it becomes more a matter of personal achievement than a collective realisation of goals. Moreover, when that leader is out of office in the next election, we see the situation going back to square one, where the question of marginalisation and caste-based atrocities create a huge void in the face of Indian politics, where leaders say things like “Being an Upper caste is a loss in politics”.

One politician says that Ayodhya has become the symbol of divide in our country, another says that elections are now contested on the basis of religion, a shift from caste-based elections. In a narrative like this, one would wonder, where does social inclusivity feature, which should have been the core of representation in politics.

Godfathers, Infighting and Accessibility

Realpolitik roughly divides Indian political parties into two categories: family run, and cadre-based.

What remains uniform within both, is the sheer need of a political Godfather if one wants to rise above their station. Clearly the party workers who found themselves at a favorable spot in the eyes of the leaders, make it to powerful positions; and those who are not, remain mere volunteers for a long time, never getting a ticket or contesting an election.

Infighting is another aspect which Realpolitik talks about; which is about groupism within parties and people getting election tickets on the basis of their internal connections, after scapegoating fellow workers and reaching a position of influence within the chain of command.

Realpolitik often points to the fact, through interviews, that founders or leaders of a political party become inaccessible to their own party workers after a point, having contested elections, or winning a few seats in the Vidhan Sabha. One would imagine, if a party worker is calling their own leaders inaccessible, how accessible would the latter be, to the common people, who put them in the office in the first place?

Infighting within parties makes it hard to analyse if our policy makers are in a position because they deserved it, or because they overtook a better candidate with less assets, privilege and money.

Women in politics

While Realpolitik has narratives from about two dozen people active or formerly active in politics, the number of women interviewed is negligible. I do not mean to critique the book or the author herself, when I say this. I simply mean that women in politics, is a harsh reality of negligible representation and no inclusivity whatsoever.

Realpolitik talks about the lack of women in politics, and the tokenistic presence, if any. It points to the fact that women’s role in politics is actively minimised, their efforts and achievements blatantly ignored. In the cases where these women are talked about by male politicians, a picture of ‘Mother’ and ‘Sister’ is clearly painted in the interviews. While it is obvious that the worth of women is reduced to that of a man’s relative or representative, it is also true that women are simply not allowed to venture into public politics, because of a variety of reasons.

Realpolitik talks about the lack of women in politics, and the tokenistic presence, if any. It points to the fact that women’s role in politics is actively minimised, their efforts and achievements blatantly ignored. In the cases where these women are talked about by male politicians, a picture of ‘Mother’ and ‘Sister’ is clearly painted in the interviews.

Also read: Aunty, Didi, Bhabhi, Tai: How Indian Women Politicians Are ‘Domesticated’ So They Fit In

From having to shoulder the responsibilities of being a wife, to facing character assasination, and being called ‘excessively ambitious’ in case she does want to fight for her rightful position in politics, a woman’s journey is riddled with double-edged knives.

On the other hand, it seems that women may have also internalised misogyny.

At one point, a politically active woman says that she has seen ambitious women lured and seduced by men, and they too take up that route to get ahead in politics.

It is problematic to see how women are also blamed for their sexuality (in politics, like any other field) and for owning up to it, while it is actually the conditioning which does not see beyond a woman’s body; and even if it does, it does so to embody women as their male relative’s extension.

Realpolitik is definitely a must read for anyone who wants a comprehensive take on the Indian politics, especially because it lays the canvas out for the reader, to form opinions of their own, simply guarded by the facts stated by those who have been actively involved in politics since decades. It acts like a much-needed kaleidoscopic view of politics, something most of us are unable to find.

About the author(s)

Ayushmita is a gender and sexuality educator, an amateur researcher, and a Freelance Consultant with an interest in Policy and Development with a gendered approach. She carries a notebook each time she goes to the movies, to jot down all the problematic instances of the film she can rant about later. She is a plant mother and contrary to popular belief, naming plants does not mean she is a loner.