Article 370 of the Indian Constitution traces its origins to the historic Instrument of Accession, a pivotal agreement signed between India and the Sovereign State of Jammu and Kashmir on October 26, 1947. This constitutional provision bestowed upon the state a distinctive and special status, setting it apart from other regions within the Indian Union.

In October 1949, the implementation of Article 370 marked a significant milestone, granting Jammu and Kashmir internal administrative autonomy. This autonomy empowered the region to enact its laws, except for key domains such as finance, defence, foreign affairs, and communications, which remained under the jurisdiction of the Indian government. The state further fortified its identity by establishing its constitution and flag, while also imposing restrictions on property rights for outsiders.

The autonomy of Jammu and Kashmir witnessed additional reinforcement in 1954 with the introduction of Article 35A, supplementing Article 370. This provision granted the state legislature the authority to confer exclusive privileges upon its permanent inhabitants, adding another layer to the unique status of the region.

Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, as outlined in the Constitution of India 1949, provides provisions concerning the State of Jammu and Kashmir. This article delineates unique considerations for the state, limiting the application of Article 238 and confining Parliament’s legislative powers to specific matters as outlined in the Instrument of Accession. It specifies that certain provisions of the Constitution, such as Article 1, shall apply to Jammu and Kashmir, subject to exceptions and modifications at the discretion of the President. The consultation or concurrence of the State Government, led by the recognised person acting on the advice of the Council of Ministers, is crucial for issuing orders related to the state’s governance.

The article also addresses the role of the Constituent Assembly in decision-making and grants the President the authority, through public notification, to modify or cease the operative nature of Article 370, contingent upon the recommendation of the Constituent Assembly. In essence, Article 370 establishes a framework for the temporary and unique constitutional status of Jammu and Kashmir within the Indian Union, emphasizing consultation and concurrence in governance matters.

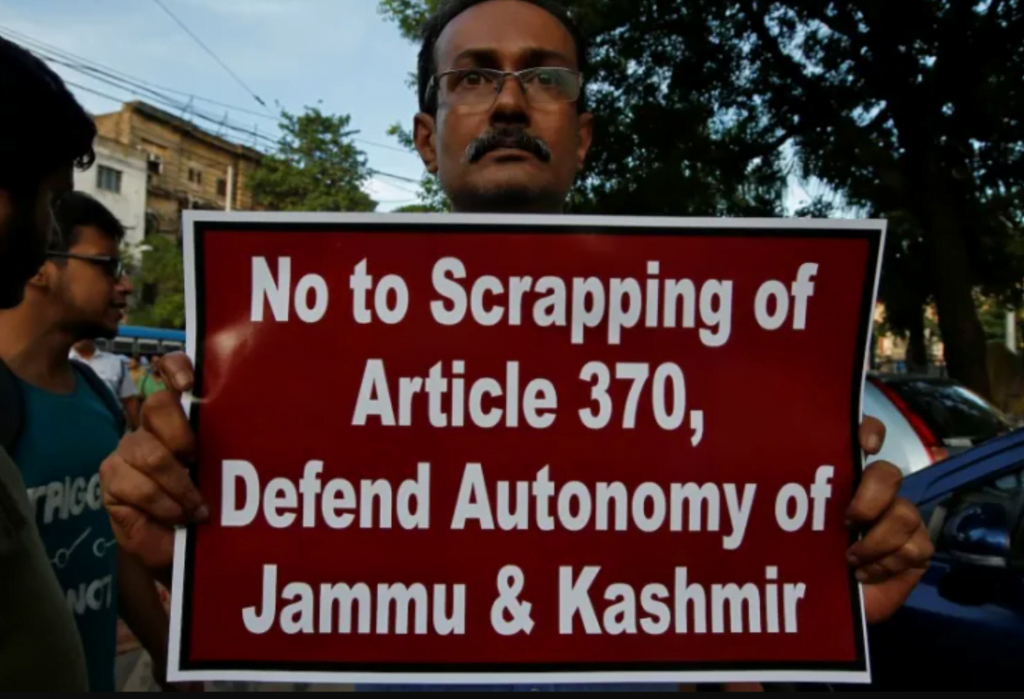

2019 aftereffect of Article 370

The trajectory of Article 370 took a significant turn in 2019. According to Article 370(3), any changes to this provision required the consent of the Jammu and Kashmir Constituent Assembly.

Yet, since the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly in 1957, an alternative approach was needed. The Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 2019, issued by the President on August 5th, creatively substituted “Legislative Assembly (of Jammu & Kashmir)” for “Constituent Assembly,” in Article 370(3). This move was executed through Article 370(1), modifying Article 367—the interpretation provision—rather than directly amending Article 370.

The culmination of the Union Government’s decision in 2019 to revoke Jammu and Kashmir’s (J&K) special status under Article 370 of the Constitution reached a significant milestone on December 11, 2023, when the Supreme Court upheld the decision.

On the same day, BJP MP Amit Shah proposed a Statutory Resolution in the Rajya Sabha, leveraging the changed provisions to essentially repeal Article 370. The Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Bill, 2019, which received parliamentary approval on August 6, further divided the state into two Union Territories—Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh—with the former granted its legislative Assembly.

The culmination of the Union Government’s decision in 2019 to revoke Jammu and Kashmir’s (J&K) special status under Article 370 of the Constitution reached a significant milestone on December 11, 2023, when the Supreme Court upheld the decision. In its ruling, the court underscored that the State of J&K lacked internal sovereignty, a key factor in determining that the State Government’s consent was not a prerequisite for the implementation of the Indian Constitution within the region.

Crucially, the court declared Article 370 to be a temporary measure, affirming the evolving nature of the constitutional landscape. This landmark decision not only validated the constitutional validity of the abrogation but also clarified the legal standing of J&K within the broader framework of the Indian Constitution.

Historical and Legal Foundations the Special Status

On August 15, 1947, when Britain departed India, the British Indian Empire was divided into the dominions of India and Pakistan. The British proclaimed both regions to be sovereign, with total control over their internal and external affairs. When British India gained its independence, the only recognised political entities were princely states and British provinces.

Jammu and Kashmir, Hyderabad, Junagarh, and the Khanate of Kalat remained unconvinced, even though 561 princely states had already acceded to the new dominion of India by August 15, 1947.

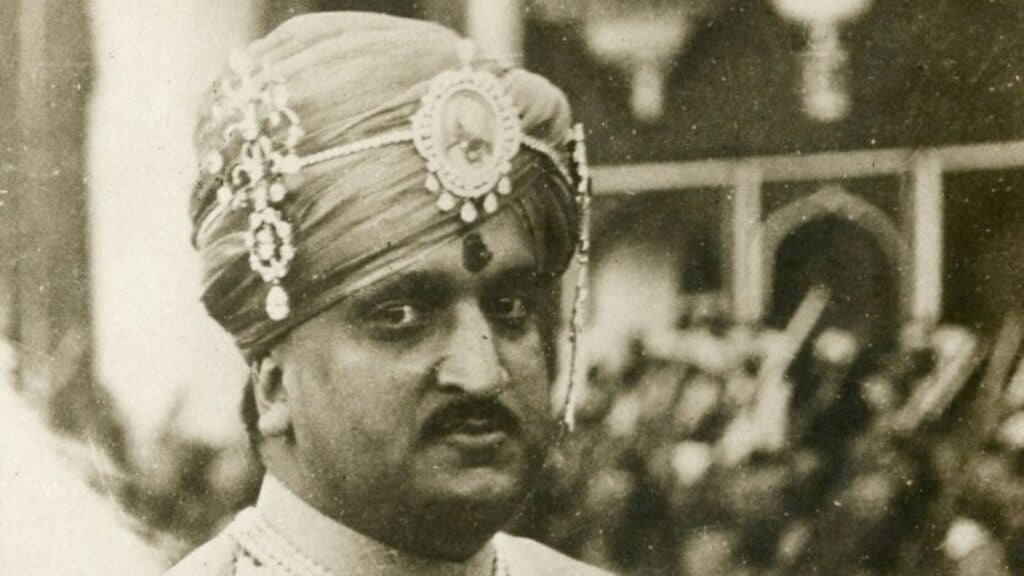

Although the princely states had the freedom to choose their rulers, they were required to give geographic proximity the weight they deserved. Even though the great majority of people in Maharaja Hari Singh’s territory were Muslims, the monarch of Jammu and Kashmir, was a Hindu.

Since joining either India or Pakistan would have meant giving up his monarchical power, he had fought to keep his state independent. To ensure that trade, communication, and travel would go as they had before the division of the monarchy, Maharaja Hari Singh signed a Standstill Agreement with Pakistan.

Nevertheless, a similar agreement with India was unable to materialise. Later, on October 21, 1947, Pakistan deployed tribal Muslims to seize control of the remaining portion of Jammu and Kashmir after breaking the terms of the Standstill Agreement, stopping supplies intended for the state and occupying a portion of the region.

Significant problems with law and order existed throughout the state. The unusual circumstances required Maharaja Hari Singh to sign the Instrument of Accession with India. Consequently, in the concluding phases of the Indian Constitution-making endeavour, N. Gopalaswami Ayyangar presented draft Article 306A (later renumbered as Article 370) to the Constituent Assembly.

The objective of this draft provision was to afford Kashmir a distinctive status within India’s federal framework. While introducing the Article, Ayyangar encountered an interruption from Maulana Hasrat Mohani, the founder of the Communist Party of India, who questioned the rationale behind such differentiation.

In response, Ayyangar clarified that the unique status was necessitated by the exceptional circumstances prevailing in Kashmir. Distinguished from other states, Kashmir was considered unprepared for full integration into the emerging Republic, primarily due to the ongoing regional conflict and the involvement of the United Nations in the matter. After the discussion, Draft Article 306A was endorsed by the Constituent Assembly, eventually becoming Article 370 in the Constitution of India in 1950. This constitutional provision affirmed the distinct status of Jammu and Kashmir, acknowledging its right to formulate a State Constitution.

The Indian Constitution went into effect on January 26, 1950, bringing with it Article 370 and its three main frameworks. The concurrence of its government was required, meaning that legislation in Jammu & Kashmir had to conform to the Instrument of Accession. There was no other provision of the Constitution that pertained to Jammu & Kashmir save Article 370 and Article 1.

Before implementing any modifications or exceptions, the President may confer with the State Government. Of particular note was the fact that Article 370 could only be changed or removed with the approval of the Jammu & Kashmir Constituent Assembly.

The Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 1950, which President Rajendra Prasad issued later, under Article 370, outlined the powers that Parliament would have. The order introduced Schedule II with amended requirements and specified topics falling within the categories of communications, defence, and external affairs. Under the direction of Prime Minister Sheikh Abdullah, the Jammu and Kashmir Constituent Assembly set out to prepare a constitution on October 31, 1951.

The Jammu and Kashmir administration was granted residuary powers in 1952 by the Delhi Agreement. It gave the state access to the Indian Constitution’s provisions. By introducing Article 35A for special rights and guaranteeing territorial integrity, President Prasad’s 1954 decree was approved by the Constituent Assembly.

The Supreme Court’s periodic decisions about Article 370 emphasised the significance of the final decision of the Constituent Assembly as stipulated in Article 370(3) in the case of Prem Nath Kaul vs Union of India. It emphasised the Maharaja’s legislative authority and defended the Big Landed Estates Abolition Act, of 1950.

The Supreme Court affirmed the modification of Lok Sabha representation by a Presidential Order in Puranlal Lakhanpal vs The President of India. The case of Sampat Prakash vs State of Jammu & Kashmir established that Article 370 remained in effect even after the Constituent Assembly was dissolved.

The Supreme Court affirmed a lawsuit against the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002 in State Bank of India v. Santosh Gupta, highlighting Article 370’s continuing validity until the Constituent Assembly recommends its termination.

Article 370 wasn’t meant to be Permanent

Barely ten years after it was ratified, Article 370 of the Indian Constitution has been significantly modified. The procedure began immediately in 1950 with the release of the Constitutional Application Order 1950. Following that, the State’s leadership and the federal government had many meetings that ultimately resulted in the 1952 Delhi Agreement, which agreed to apply to the State of J&K on several matters not included in the Instrument of Accession. In this perspective, Pandit Nehru’s and Gulzari Lal Nanda’s remarks are significant.

On November 27, 1963, “Pandit Nehru stated on the Lok Sabha floor that Article 370 had been gradually undermined and continued to do so.” A year later, on December 4, 1964, on the floor of the Lok Sabha, the then-home minister Gulzari Lal Nanda declared, “Article 370 is a tunnel to take the Constitution of India to Jammu and Kashmir. He said that whether it is retained or not won’t matter in the end because all that would be left is the shell, empty of anything within.”

The J&K Constituent Assembly and the state administration both endorsed the 1954 Order (The Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 1954) as required. However, 42 directives from the President have since been issued, all of which have modified the 1954 mother order. 94 out of the 97 items in the Union List and 26 out of the 47 entries on the Concurrent List have been implemented using these directives from succeeding central governments.

Additionally, they have declared 260 of the 395 Indian Constitutional Articles to apply to J&K. In 2019, the Government of India made all provisions of the Indian Constitution applicable to the State of Jammu and Kashmir after introducing the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Act, 2019 in Parliament on August 5, 2019.

The 2019 Presidential Order, published in August 2019, and announced on August 6, has changed India’s constitutional relationship with J&K, putting the state on an equal footing with the rest of India. The J&K Reorganization Act of 2019 separated the state of J&K into two Union Territories (hereafter UT) in the form of UT from J&K one Legislative, similar to UT of Puducherry, and UT of Ladakh, similar to UT of Chandigarh.

Political reaction to the Article 370 verdict

The decision of the apex court has created ripples across the political circles across the country. “Rather than our loss,” Mehbooba Mufti (former CM Jammu and Kashmir) said in a video address to her party workers after the SC delivered its verdict “It is the idea of India which has suffered a defeat today. The betrayal has come from them, not us. By terming Article 370 as a ‘temporary’ provision, the country has been weakened while those powers who termed J&K’s accession with India as ‘temporary’ have got strengthened.”

As Article 370 comes to an end in the context of the Constitution, it leaves behind a legacy of discussions, disagreements, and significant rulings. In addition to changing Jammu and Kashmir’s government structure, the 2019 constitutional amendments have prompted debates on federalism, autonomy, and the delicate balance between unity and diversity within the Indian Union.

“We knocked on the doors of SC with the hope of justice. I respect the court’s decision. We may have failed, and the decision may be disappointing, but it is a temporary setback. Ours is a political fight and we will fight it within the ambit of law,” Omar Abdullah (former CM of Jammu and Kashmir).

Hours before the Supreme Court’s Article 370 Judgment backing the Centre’s move to scrap Jammu and Kashmir’s special status, senior lawyer and former parliamentarian Kapil Sibal posted that “some battles were fought to be lost.”

As Article 370 comes to an end in the context of the Constitution, it leaves behind a legacy of discussions, disagreements, and significant rulings. In addition to changing Jammu and Kashmir’s government structure, the 2019 constitutional amendments have prompted debates on federalism, autonomy, and the delicate balance between unity and diversity within the Indian Union. This evolution’s comprehensiveness shows how complicated constitutional arrangements are and how they affect different parts of a country.

References:

- Gupta, A. (2022) The Story of Jammu and Kashmir and Interpretation of Article 370 of the Constitution of India, Global Journal of Human-Social Science Research, Volume 21, Issue 15 A.

- Goel and Sharma. (2020) Anatomy of Article 370 and 35A: Tracing the Past to the Present, CPJ Law Journal, Volume X, Issue 1, Page 28-45.

- Singh, M, (n.d) Articles 35-A, 370, the Supreme Court of Indian and Jammu and Kashmir (with Special Reference to Constitutional History) academia.edu.

- Tewari, T. (2012) Article 370 of Constitution of India: Need Parliamentary Debate, Commentary on Constitution of India, Edition 8 Volume 10

- https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/article-370-supreme-court-abrogation-of-special-status-of-jammu-and-kashmir-244198

- https://www.scobserver.in/journal/article-370-in-the-supreme-court/

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/12/11/whats-article-370-what-to-know-about-india-top-court-verdict-on-kashmir

- https://frontline.thehindu.com/news/jammu-kashmir-supreme-court-upholds-abrogation-of-article-370-in-landmark-decision/article67627243.ece

- https://thewire.in/history/article-370-understanding-the-history-legal-contexts-and-why-it-matters

- https://www.scobserver.in/journal/article-370-of-the-constitution-a-timeline/

- https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1573666/

- https://www.indiandefencereview.com/spotlights/jawaharlal-nehru-shiek-abdullah-1953-agreement/

About the author(s)

She is a Research Scholar, currently dedicated to pursuing her doctoral studies in the field of Political Science and International Relations. With more than ten years of hands-on experience across various media-related domains, she has established herself as a seasoned Media Professional.