Have you ever noticed how the word ‘art’ often seems to mean different things in different conversations, even within feminist spaces? Sometimes it points clearly to paintings, installations, or exhibitions in galleries. At other times, it is used more loosely, to gesture towards creativity, expression, or culture, without quite naming forms like dance, theatre, singing, or performance in the same breath. I began noticing this pattern while paying attention to how the word ‘art’ was being used, what it included, what it quietly excluded, and what assumptions sat beneath it. The more I listened, and the more I read, the clearer it became that this ambiguity was not innocent. What initially appeared to be a matter of language or habit revealed itself as a structured hierarchy, shaped by institutions, markets, and histories of power. A seemingly neutral question of terminology opened up larger questions about value, legitimacy, and whose creative labour is allowed to count.

In contemporary conversations on gender and art in India, the word ‘art’ is often used as if its meaning is obvious and universally agreed upon. In practice, however, it is narrowly applied. Painting, sculpture, installation, and photography are readily recognised as “art,” while embodied practices such as dance, theatre, singing, and performance are frequently pushed into parallel categories like “culture,” “tradition,” or “entertainment.” This division is so normalised that it often goes unquestioned, even within feminist spaces.

Yet this hierarchy is neither natural nor inevitable. It is produced through institutions, markets, and histories that determine which forms of expression are worth preserving, funding, and theorising, and which are not. What gets recognised as art is shaped less by expressive depth than by whether it can be owned, archived, displayed, and sold. What falls outside these systems is often treated as secondary or merely expressive.

For feminist politics, this distinction is not trivial. Many of the practices that are demoted within dominant art hierarchies, such as dance, performance, song, and collective ritual, are historically associated with women and with Dalit, Bahujan, and Adivasi communities. Their marginalisation within the art world mirrors broader social patterns, where labour tied to the body, care, repetition, and community is devalued even as it is aesthetically consumed. To interrogate what counts as “real” art, then, is also to interrogate how gender and caste shape systems of cultural value.

What we recognise as art is not determined by creativity alone. It is shaped by institutions such as museums, galleries, art schools, funding bodies, and markets that decide what is worth displaying, preserving, and writing about. These institutions tend to privilege forms that can be objectified, turned into discrete, stable entities that circulate through elite cultural spaces.

Yet this hierarchy is neither natural nor inevitable. It is produced through institutions, markets, and histories that determine which forms of expression are worth preserving, funding, and theorising, and which are not. What gets recognised as art is shaped less by expressive depth than by whether it can be owned, archived, displayed, and sold.

This institutional logic has consequences. Visual art forms are positioned as the primary carriers of artistic legitimacy, while other practices are classified differently. Dance becomes performance, theatre becomes entertainment or activism, and singing becomes culture. These categories may appear descriptive, but they are also hierarchical. They determine what is eligible for serious critique, long-term archiving, and historical canonisation.

Feminist scholars have long argued that such classifications reflect broader hierarchies between mind and body, permanence and ephemerality, and ownership and labour. In the Indian context, these hierarchies intersect with gender and caste in particularly sharp ways. The question is not simply what art is, but who has the authority to define it.

While deep diving into this narrative, a question kept appearing in my notes: Why is visual art institutionally privileged? The more I looked, the more it became apparent: it is because it aligns with systems of ownership and validation that have historically centred patriarchal authority.

Why is visual art institutionally privileged?

Visual art fits comfortably within systems of ownership and exchange. A painting can be bought, displayed, insured, archived, and resold. Its value can be quantified, tracked, and reproduced through catalogues and collections. This material stability allows visual art to circulate smoothly through galleries, museums, and private collections, acquiring legitimacy through both visibility and price.

Performance-based practices, however, operate differently. Dance, theatre, and song are live, time-bound, and often collective. They rely on bodies, repetition, and sustained labour rather than on a single finished object. Because they resist permanence and possession, they sit uneasily within institutions designed to store and trade objects. Their difficulty in being archived or commodified becomes a reason for their marginalisation.

Even when women achieve prominence within performance traditions, their work is rarely positioned at the centre of contemporary art discourse. Instead, it is framed as cultural expression, heritage, or activism – important, perhaps, but not quite art in the fullest sense.

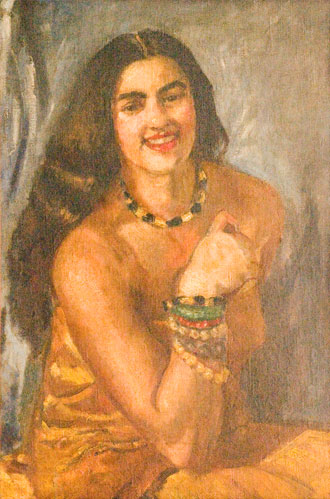

Moreover, the demotion of performance-based art is also deeply gendered. Historically, women’s labour has been associated with the body, care, emotion, and repetition, qualities that patriarchal systems routinely devalue. This association extends into the arts. Female dancers, singers, and performers are often celebrated aesthetically while being denied authorship, permanence, or institutional recognition.

Their work is visible, yet disposable. Performances are consumed in the moment and then allowed to disappear, leaving little trace within official archives. A female body is central to the spectacle, yet heavily policed through moral scrutiny and respectability politics. Visibility does not translate into power or legitimacy.

Even when women achieve prominence within performance traditions, their work is rarely positioned at the centre of contemporary art discourse. Instead, it is framed as cultural expression, heritage, or activism – important, perhaps, but not quite art in the fullest sense. This distinction allows institutions to benefit from women’s creative labour while withholding the forms of recognition that grant lasting authority.

Caste-based hierarchy

The marginalisation of performance is not only gendered, it is also caste-marked. Many performance traditions in India are rooted in Dalit, Bahujan, and Adivasi communities. These practices are frequently framed as “folk” or “traditional”, stripped of individual credit, and absorbed into narratives of national culture that erase political context and lived experience.

Upper-caste artistic practices, by contrast, are more likely to be intellectualised, historicised, and canonised. They are discussed in terms of innovation, authorship, and aesthetic philosophy. Marginalised practices are aestheticised without being theorised, celebrated without being politicised.

This process of folklorisation allows dominant groups to consume the cultural labour of marginalised communities while distancing themselves from the conditions under which that labour is produced. Art becomes heritage rather than resistance, tradition rather than testimony. In this framework, caste operates quietly but decisively, shaping whose creativity is seen as contemporary and whose is relegated to the past.

Feminist artists and practitioners have long challenged the assumptionthat art must exist as a discrete, collectible object to be taken seriously. Through installation, performance, moving image, and other interdisciplinary practices, they have foregrounded art as process rather than product and as experience rather than possession. These approaches directly resist institutional preferences for permanence, ownership, and visual fixity.

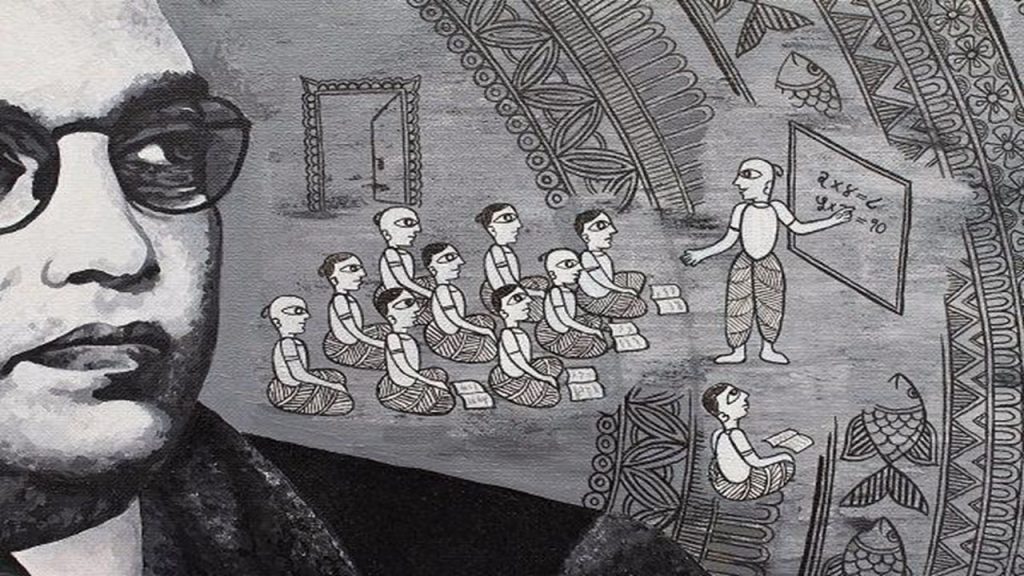

The work of Nalini Malani exemplifies this challenge. Through immersive installations, shadow plays, and video-based practices, Malani engages histories of gendered violence, displacement, and erasure. Her work resists stable viewing and material permanence, instead demanding embodied engagement with fragmented narratives and collective memory. In doing so, it disrupts the logic through which artistic value is tied to durability and market circulation.

The marginalisation of performance is not only gendered, it is also caste-marked. Many performance traditions in India are rooted in Dalit, Bahujan, and Adivasi communities. These practices are frequently framed as “folk” or “traditional”, stripped of individual credit, and absorbed into narratives of national culture that erase political context and lived experience.

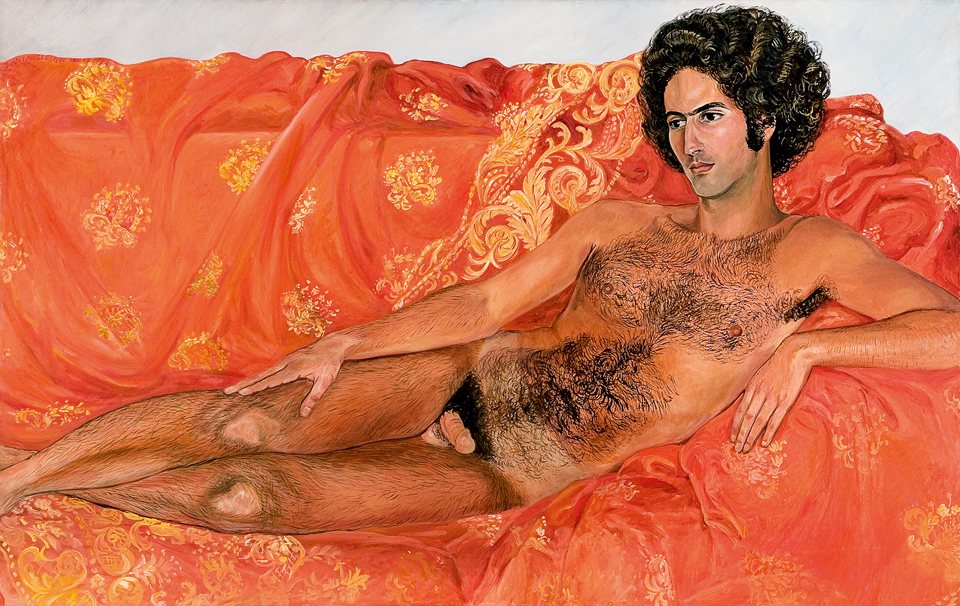

A similar tension is evident in the marginalisation of performance-based practices, as seen in the controversy surrounding RLV Ramakrishnan. Despite rigorous training and cultural legitimacy, performance is frequently devalued within institutional hierarchies, where authority is shaped by entrenched ideas of respectability and control over bodies.

Taken together, these examples demonstrate that feminist challenges to object-based art hierarchies do not simply seek inclusion within existing systems of validation. They expose how those systems are structured to privilege certain forms, materials, and bodies over others. By foregrounding ephemerality, embodiment, and political context, such practices unsettle the very criteria through which art is recognised, archived, and remembered.

The politics of intimacy in art

This hierarchy does not operate only through medium or material; it also shapes how political expression itself is recognised. One of the most persistent ways in which female artistic practices are marginalised is through the devaluation of the private and the intimate. Interior spaces, emotional quiet, and everyday bodily experiences are often dismissed as apolitical or minor, even though feminist movements have long argued that the personal is political.

When female artists centre intimacy, they are frequently read as retreating from urgency or confrontation. Loud, spectacular, or slogan-driven forms of expression are more readily recognised as political, while quietness is mistaken for passivity. This reflects a broader discomfort with forms of resistance that do not conform to dominant aesthetics of protest.

To take intimacy seriously as subject matter is to challenge the assumption that politics must always be public, visible, and dramatic. It is also to recognise how deeply gendered expectations shape our understanding of what counts as meaningful expression.

In a socio-political climate marked by increased surveillance of bodies, expression, and dissent, the politics of art cannot be treated as secondary. When feminist spaces uncritically accept narrow definitions of art, they risk reproducing the very exclusions they seek to challenge.

Interrogating how gender and caste shape what is considered expressive, creative, and worthy of preservation allows feminist critique to move beyond representation toward deeper questions of labour, legitimacy, and power. It forces us to ask not only who is visible, but who is valued; not only who is included, but on what terms.

Art does not exist outside these structures. It reflects them, reinforces them, and, at times, resists them. To question what counts as “real” art is therefore not an abstract cultural exercise but a necessary feminist intervention, one that insists that even our most expressive spaces are shaped by inequality and that they can be reimagined otherwise.

Comments:

Comments are closed.