Suppose you type “top sex therapist in India” or “best sexologist near me” in any search engine. In that case, it gives a reasonably long list of ‘specialists’ with different academic qualifications who provide sex therapy. Let’s keep the issue of what makes them specialists aside, given that there is no formal education in India on sex therapy. The point here is that the increase in the number of providers is possibly a result of more people openly seeking medical or counselling care for sexuality-related issues.

In times of globalisation and high-speed internet, concepts surrounding sexuality are evolving fast. Individual choice, freedom, and pleasure are gaining importance in people’s narratives. People are asking questions about their sexuality and their decisions. Members of sexual minorities are speaking openly about their mental health problems. Partners are openly expressing concerns about intimacy as well as non-normative sexual practices. It is not to say that there is no stigma around sexuality, and most people are openly able to express their sexuality. Certainly not!

However, some change is happening, at least in the urban areas. It is a good sign that people are seeking care from professionals. But the moot question is are they getting good quality, non-judgmental care. In this situation, it is even more critical to understand what sexuality-related knowledge is imparted to students of mental health that helps them get the required skills and knowledge for optimal performance.

Why should counsellors know about sexuality?

Sexuality, an indivisible domain of our lives, is addressed by many professionals in the health care sector, including general physicians, psychologists, social workers and others. Those professionals attempt to address sexuality-related concerns with their subjectively constructed perspective. Their approach to sexuality is strongly influenced by their culture, upbringing, academic training, and exposure.

A research demonstrated that practitioners with higher knowledge about sexuality were able to decrease their perceived barriers and become more comfortable in addressing the sexual health of their clients (Russel, 2012).

As a counsellor, there are typically multiple stages where it is critical to address sexuality directly and in-depth. Taking case history requires counsellors to ask clients questions about their sexual life. Similarly, at many stages, the counsellor is required to provide information about sexual health, well-being, sexual and reproductive rights, and sexual safety. Counsellors might be required to provide specific interventions to clients experiencing difficulties related to past or ongoing sexual abuse or reassure clients experiencing guilt because of their gender identities.

These interventions require in-depth knowledge of sex and sexuality. Also, living in a largely heteronormative setup, counsellors have to be aware of their language and gestures and develop competency to be more affirmative of sexual minorities. However, the skills and knowledge required to address this particular niche are unique, and the lack of those can lead to barriers to providing the service efficiently. (Miller, Byers, 2011)

The need for introducing sexuality-related training in the counselling curriculum has been highlighted globally (Miller,2008). Sexuality is potentially an issue for all clients in some way or the other, and hence counsellors need to address it. Further, because of the negative and stigmatising social attitudes, issues around sexuality are ridden with guilt and not openly talked about by the clients; hence counsellors need to make additional efforts to provide a safe and non-judgemental space for people to talk (Gupta, 2019). Moreover, due to the lack of comprehensive sexuality education in schools, the clients might lack basic knowledge about sexuality where the counsellor is expected to impart scientifically correct knowledge (Burnes, Singh, Witherspoon, 2017).

All these reasons are relevant to the Indian context as well. In India, sex and sexuality are considered a topic discussed under the covers, in whispered tones. It is joked upon, giggled about, teased about but rarely pondered upon. Graduate and postgraduate programs in India rarely include sexuality and tend to focus on only selective topics while overlooking others. As a result, untrained practitioners who have to provide sexuality-related care don’t feel comfortable doing so. Research among practising psychiatrists in India showed significant hesitancy while talking about sexuality, especially with elderly and adolescents, while taking sexual histories and discomfort while talking to people from LGBTQAI (Lesbian Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Asexual, Intersex) communities. (Hedge et al., 2018)

How is sexuality included in the curriculum?

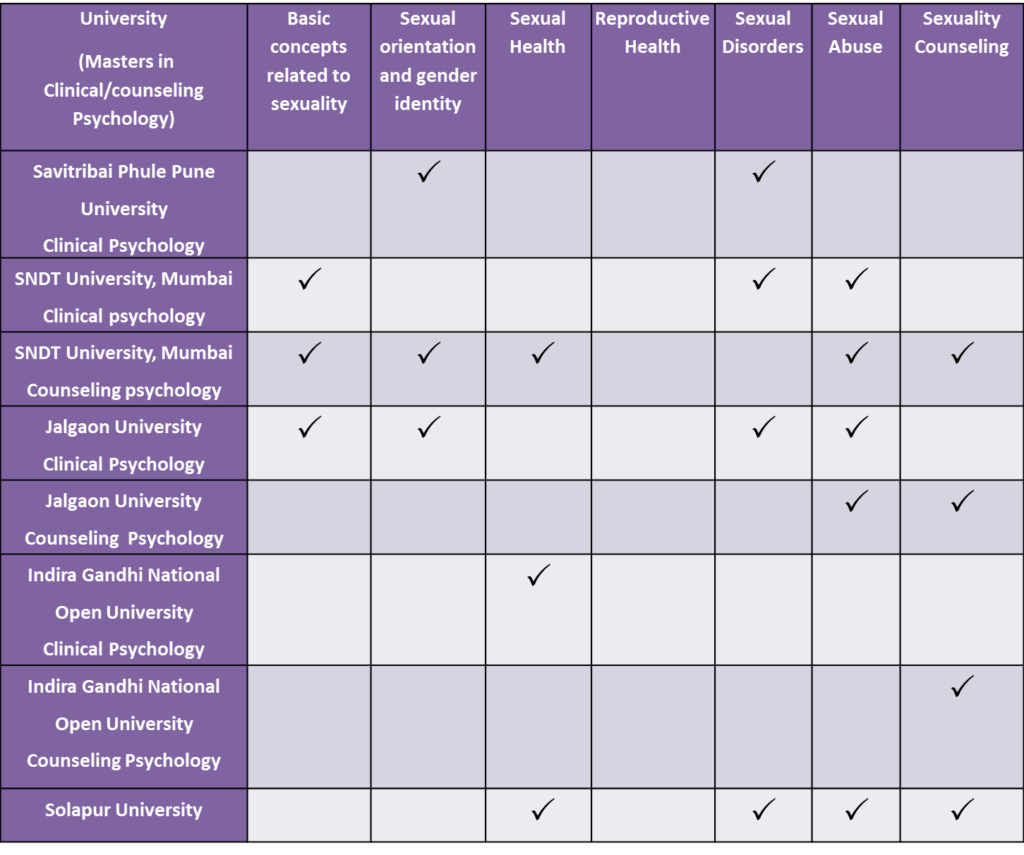

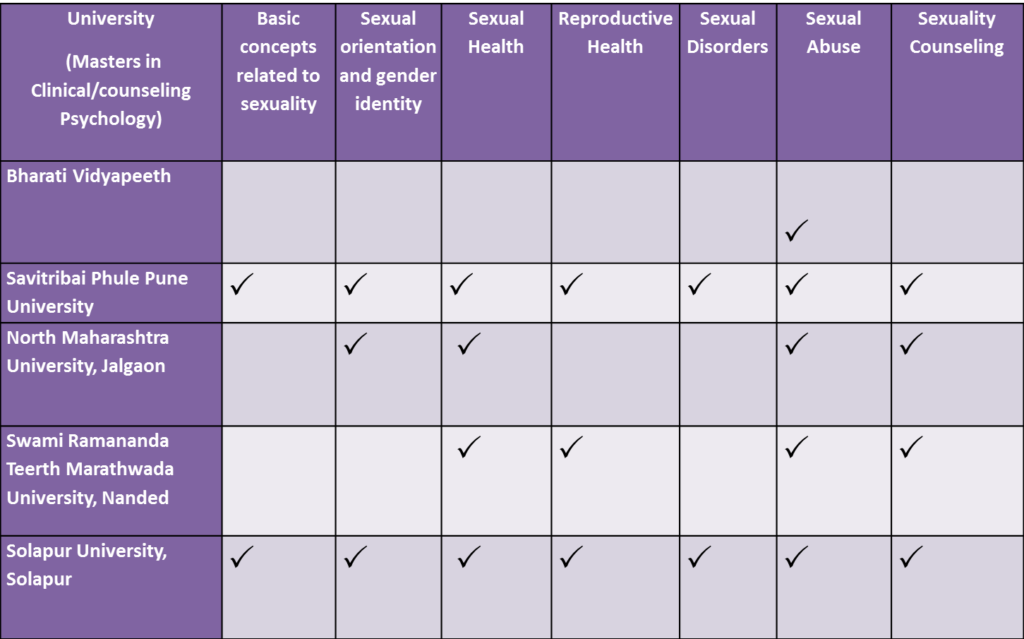

To get a realistic understanding of sexuality-related training, we reviewed the syllabi of universities in Maharashtra. We focused on two courses — Masters in Psychology (clinical and counselling) and Masters in Social Work because the enrolled students are most likely to practice counselling in their careers.

After reviewing the syllabi, we created eight broad categories and classified the topics mentioned in the syllabi.

The categories included an introduction to sexuality, gender identity and orientation, sexual health and reproductive health, sexual disorders, STIs, sexuality counselling and sexual abuse. Introduction to sexuality included misconceptions about sexuality, definitions of sexuality, the importance of sexuality education etc. Sexual health consisted of any reference to male/female sexual anatomy and contraception, masturbation, STI etc. In vitro fertilisation, infertility and pregnancy, and post-partum care were classified under reproductive health.

What did we find?

After analysing, the following matrix was developed.

Image source: Eesha Lavelekar

No one course has covered all the important topics in the curriculum. One common trend that can be established across all the courses is no common propagated understanding of sexuality. In the course on social work, two universities appear to be ticking most of the boxes. However, based on the course syllabus document, it was unclear how far they covered the different subtopics in each category.

Jalgaon University includes a unit entitled Human sexuality. The first sub-unit under this is ‘Normal Sexuality’, and the remaining other subunits are related to sexual pathologies (for example, gender dysphoria, paraphilia, impulse control disorder etc.). With such a categorisation, it seems quite possible that the (hetero) normative sexuality is taught as normal (read as healthy) and all other expressions of sexuality as pathological.

In psychology-centred courses, there are two specialisations- clinical and counselling psychology. Both courses tended to focus on different aspects of sexuality. Clinical psychology stressed sexual dysfunctions, paraphilia and gender dysphoria. On the other hand, counselling psychology gave more emphasis on couples, family and marriage counselling.

Only one course mentioned child sexual abuse from a legal and preventive perspective.

Gender was commonly addressed through the lens of gender dysphoria (the distress caused by not feeling comfortable with one’s sex assigned at birth) in psychology courses. The social construction of gender was only mentioned in selective social work courses.

The theme of counselling in the context of sexuality revolves around marriage, such as marriage/ premarital/ couples/ family counselling, etc.

Along with the contents/topics of the syllabus, understanding how these topics are tagged provided important insights into how sexuality is conceptualised. Entireties of gender identity and paraphilia are classified under sexual dysfunctions, disease, and perversion. They are approached with a negative attitude, labelled as impairments, and pathologised as disorders. The topic of internet sexuality and pornography is highly overlooked. Only one MSW course introduces it from a legal perspective.

A binary and heteronormative perspective is dominant, omitting the concerns of non-binary people.

Although family and marriage counselling are included in the curriculum, some topics related to sexuality, such as STIs, are classified as optional or provisional. Hence not all students learn it as a mandatory part of their course. However, SNDT University and Solapur university have introduced two topics that are LGBTQIA inclusive( e.g . Alternate family patterns).

The limited topics included in the curriculum point out the tendency to pathologise sexuality and focus on dysfunctions and disorders. The positive and affirmative aspect of sexuality remains completely neglected. The positive consequences of achieving sexual well-being, the role of pleasure in sexual growth, and indicators of sexual well-being are not discussed in any of the courses

The way forward

The review shows that sexuality is not entirely missing from the curriculum. However, what is covered and how it is approached clearly show the lack of clarity on what should be taught and what perspective. There is ambiguity surrounding the knowledge as well as skill-building. Lack of affirmative and rights-based sexuality training for students who are likely to work as counsellors and some of them also as sex therapists could significantly impact the quality of counselling. Hence it is high time that we introduce sexuality training in the courses with considerations pointed out below.

Different courses must have a common understanding of sexuality. The courses should be built using an evidence-centred and human rights-based approach.

For a long time, sexuality has been approached from a risk-centric perspective which should be changed to a pleasure-based approach.

Given the importance of understanding sexuality in the counselling process, learning about it should be included in the mandatory syllabus at an introductory level.

Also read: “Nobody Affirmed My Queerness”: Experience Of Childhood Counselling Sessions.

Critical thought must be given to the language which medicalises sexuality or reflects only a heteronormative worldview.

The courses, their language, and examples largely centre around marriage. It is important to distance from marriage-centred/family-centred understanding of sexuality to become more inclusive.

Also read: Feminist Therapy: Converging Social And Personal Changes In Therapeutic Traditions

Eesha Lavalekar has completed a Masters in Clinical psychology and is currently working with a Pune-based NGO named Prayas Health Group. Eesha can be found on Instagram.

Featured image source: Shreya Tingal for Feminism In India